Despite the Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives stipulating the formation of parliamentary friendship and fraternity groups, the House continues to fall short of its mandate to activate parliamentary diplomacy, effectively stalling the mechanisms at its disposal.

Download article

Introduction

Parliamentary diplomacy has evolved into a critical instrument for fostering cooperation among nations and expanding channels of communication beyond the traditional framework of formal diplomacy. Parliaments today are no longer confined to legislation, governmental oversight, and policy evaluation; they have emerged as proactive platforms supporting foreign policy by strengthening relationships with their counterparts worldwide.

In Morocco, the need for more dynamic and effective parliamentary diplomacy has grown, particularly in view of the “crucial role of partisan and parliamentary diplomacy in securing broader recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara and enhancing support for the Autonomy Initiative.”[1] The Moroccan King has consistently emphasized the importance of parliamentary diplomacy in reflecting the Kingdom’s aspirations to bolster its geopolitical position and defend its strategic interests—particularly the question of the Moroccan Sahara. In doing so, he has sometimes directly addressed Members of Parliament and, at other times, offered critique or caution regarding existing shortcomings.

Building on an analytical methodology supported by data, this paper examines the achievements of Moroccan diplomacy over the first three years of the eleventh legislative term (2021–2026) and assesses the extent to which Members of the House of Representatives (the first chamber of Parliament) have exercised the powers afforded to them by the mechanisms of parliamentary diplomacy. It also explores the general characteristics that define these mechanisms by reviewing the tools available and examining how the legislature has organized its operation. In doing so, a data-driven analysis sheds light on the principal actors in Moroccan diplomacy and the most prominent international and regional arenas it engages with, while also highlighting missed opportunities in the activation of parliamentary diplomacy tools.

This research paper adopts the concept of parliamentary diplomacy [2] as an emerging model within the field of international relations, defined as “a contemporary practice closely tied to parliamentary activity at the international level. Parliamentary diplomacy is seen as a smart complement to traditional diplomacy—typically reserved for representatives of the executive branch—where parliaments now play an increasingly significant role in international relations.” [3] Consequently, the paper is framed within the context of “soft power theory,”[4] emphasizing the parliament’s role as a political and cultural influencer that operates beyond official diplomatic channels.

In defining parliamentary diplomacy, we regard it as encompassing the various efforts undertaken by Members of the House of Representatives through available mechanisms—such as friendship and fraternity groups, permanent national delegations, and participation in regional and international conferences and meetings—to engage with other national parliaments and contribute to achieving Morocco’s foreign policy objectives. The impact of these efforts is measured by the extent to which parliamentarians enhance their country’s image, defend its core interests (such as the Sahara issue for Moroccans), and strengthen economic and political cooperation with international partners.

-

Parliamentary Diplomacy in the King’s Speeches

As Head of State and its highest representative, the King presides over the opening session of Parliament each legislative year, which begins on the second Friday of October. Since his accession to the throne in July 1999, the King has delivered a total of 26 speeches in Parliament—addresses primarily aimed at providing guidance to Members of Parliament, as well as to the government, while also offering directions to constitutional institutions and the general public.[5]

An analysis of these 26 royal speeches reveals that parliamentary diplomacy was featured in ten of them when inaugurating the parliamentary session: half of these mentions occurred during the first decade of his reign, four in the second decade, and once in the middle of the third decade.

Data gleaned from the King’s speeches [6] before both Houses of Parliament, in which he addressed the topic of parliamentary diplomacy (a total of ten speeches), shows that his first reference to it appeared in the 2003 inaugural speech of the legislative year when he urged parliamentarians to intensify their diplomatic efforts to defend the national cause. With the exception of 2008, the King consistently used his opening-of-Parliament speeches from 2003 until 2010 to encourage parliamentarians to adopt a parliamentary diplomacy he variously described as “professional,” “effective,” “proactive,” as well as “vigorous and open.”

In those speeches, the King called for “constructive initiatives and effective action to defend Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara.” His appeals to parliamentarians for activating parliamentary diplomacy then ceased in the October speeches of 2011 and 2012, before he revisited the subject the following year in a different tone. In his speech on the second Friday of October 2013, the King highlighted the shortcomings in parliamentary diplomacy, stating: “We have observed certain deficiencies in handling our foremost national issue,” affirming that parliamentary initiatives “remain insufficient.” One year later, in his address inaugurating the 2014 legislative year, the King again raised the subject of parliamentary diplomacy—this time commending parliamentarians for their substantial efforts, following the previous year’s directives, notably in countering attempts to exploit human rights issues in the southern provinces and in negotiations with the European Union on the fisheries agreement.

According to information drawn from the royal speeches at Parliament’s opening sessions, the issue of parliamentary diplomacy was absent for nine consecutive years [7] before reemerging in the latest address inaugurating the legislature on October 11, 2024. On that occasion, the King called for “more coordination between the two Houses of Parliament,” and urged the adoption of “partisan and parliamentary diplomacy that secures broader recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara.” He also advocated for “establishing suitable internal structures staffed with qualified human resources, adopting competency-based criteria in selecting delegations for both bilateral meetings and regional or international forums.”

While the royal speeches to Members of the two Houses serve as directives for parliamentary work, the fact that parliamentary diplomacy was raised in 10 out of 26 speeches underscores its significance as a complementary tool supporting the Kingdom’s official diplomacy. Nevertheless, the King’s decision to refrain from urging parliamentarians to focus on and strengthen parliamentary diplomacy during two key periods—2011–2012 and 2015–2023—may be explained by shifting priorities or by dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of parliamentary diplomacy, given the weak response to repeated calls for its activation.

Moreover, after the first lull (2011–2012), the King resumed speaking on the subject in October 2013, this time critically, pointing to flaws in parliamentary diplomacy and stressing that parliamentary efforts remain “insufficient”—reinforcing the possibility of royal dissatisfaction. A similar pattern followed the second period of silence (2015–2023). When he returned to the subject, the King outlined directives to advance and reinforce parliamentary diplomacy, particularly in supporting Morocco’s position on the Sahara, and stressed the importance of institutionalizing parliamentary diplomatic work.

Table (1): Parliamentary Diplomacy in the King’s Speeches at Parliament’s Opening Sessions

| Date of Speech | Content/Text | Notes |

| 10 October 2003 | Call for activating parliamentary diplomacy and defending the national cause with boldness and efficacy. | Call for activation |

| 08 October 2004 | Call for effective and open parliamentary diplomacy to bolster Morocco’s global stature and defend its vital interests. | Call for activation |

| 14 October 2005 | Request that Parliament adopt proactive parallel diplomacy to defend the Moroccan identity of the Sahara. | Call for activation |

| 12 October 2007 | Urging parliamentarians to pursue professional parliamentary diplomacy. | Call for activation |

| 10 October 2008 | Call for effective parliamentary diplomacy coordinated with the government. | Call for activation |

| 09 October 2009 | Request that parliamentarians take effective action to defend Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara. | Call for activation |

| 08 October 2010 | Request for continuous and effective initiatives to defend the Moroccan Sahara through parliamentary diplomacy. | Call for activation |

| 11 October 2013 | Warning about shortcomings in handling the national cause and underscoring that parliamentary efforts remain insufficient. | Warning about shortcomings |

| 10 October 2014 | Commendation of the year’s parliamentary diplomacy efforts and call to continue mobilization and vigilance against Morocco’s adversaries. | Commendation of achievements |

| 11 October 2024 | Emphasis on the role of parliamentary diplomacy in gaining further recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara, and call for adopting competency-based criteria in selecting delegations. | Call for activation |

Source: Prepared by the researcher.

-

Available Mechanisms

With the adoption of the 2011 Constitution, the Kingdom of Morocco reinforced the role of parliamentary diplomacy as a means of supporting official diplomacy to “defend the nation’s just causes and vital interests.”[8] The Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives[9] devote Part Eight to parliamentary diplomatic work, defining a set of tools and outlining their formation and competencies.

Permanent National Delegations (Shu‘ab)

Under Article 312 of the Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives (2024), the House establishes “at the start of each legislative term, and based on the principle of proportional representation of parliamentary groups, alliances, and non-affiliated Members, permanent national delegations that represent the House in international and regional parliamentary organizations in which it holds membership, while observing gender parity in accordance with Article 19 of the Constitution.”[10]

The same article stipulates that the opposition “shall contribute to these permanent delegations and to all diplomatic activities of the House in proportion to its representation,” pursuant to Article 10 of the Constitution. It also states that “the permanent national delegations shall meet periodically according to a set agenda to examine relevant issues, and they shall prepare an annual report on their work, which is submitted to the Bureau of the House.”[11]

Friendship and Fraternity Groups

Article 318 of the Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives (2024) deals specifically with the formation of parliamentary friendship and fraternity groups at the beginning of each legislative term “with parliaments of brotherly and friendly countries and international parliamentary organizations,” ensuring “proportional representation of parliamentary groups and alliances and compliance with the principle of gender parity.” The same article notes that the Bureau of the House shall establish “specific rules for these groups before the end of the first year of the legislative term, defining the principles governing their operations and methods of functioning.” Moreover, “friendship and fraternity groups shall develop their annual action plan according to the guidelines set out by the Bureau of the House, and submit it to the Bureau for approval.”[12]

III. Outcomes of Parliamentary Diplomacy

An analysis of data published on the official portal of the House of Representatives regarding its diplomatic activities[13] indicates a total of 495 diplomatic events—either hosted or participated in—since the opening of the first legislative year of the current term on October 8, 2021, until the conclusion of the second session of the third legislative year on July 25, 2024. Examining these data points provides insights into the principal actors, the focus areas of the lower chamber’s parliamentary diplomacy, the nature of its diplomatic engagements, and the achievements they have yielded in support of Morocco’s official diplomacy.

While parliamentary diplomacy serves as a complementary mechanism to its official counterpart, actual practice sheds light on the degree to which the House’s internal structures—namely, the Presidency of the House, the friendship and fraternity groups, the permanent national delegations, and the standing parliamentary committees—are involved in its activation.

Activities of the Friendship and Fraternity Groups

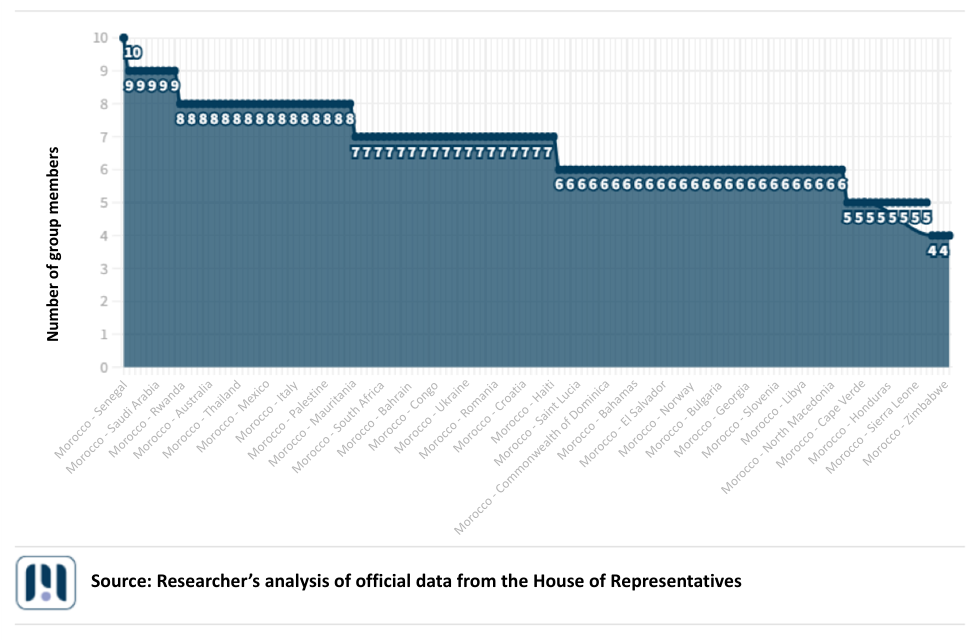

Since the start of the current legislative term,[14] the House of Representatives has formed a total of 148 friendship and fraternity groups with parliamentary bodies across various continents. Although the internal regulations of the legislative institution do not stipulate the number of members per group, available data show that membership in these groups ranges between 4 and 10 members.

Figure (1): Friendship and Fraternity Groups in the House of Representatives during the 2021–2026 Legislative Term

The data analysis indicates that the Morocco-Senegal Friendship Group attracts the highest number of Moroccan House Members, totaling 10. Meanwhile, three friendship groups—Kenya, Togo, and the Central African Republic—have the smallest membership, with only four Members each. Figures also show that around two-thirds of the House (251 Members) serve in one or at most two friendship groups. Notably, however, 41 Members do not belong to any friendship group at all, suggesting a lack of interest on their part in fulfilling their roles in strengthening parliamentary diplomacy.

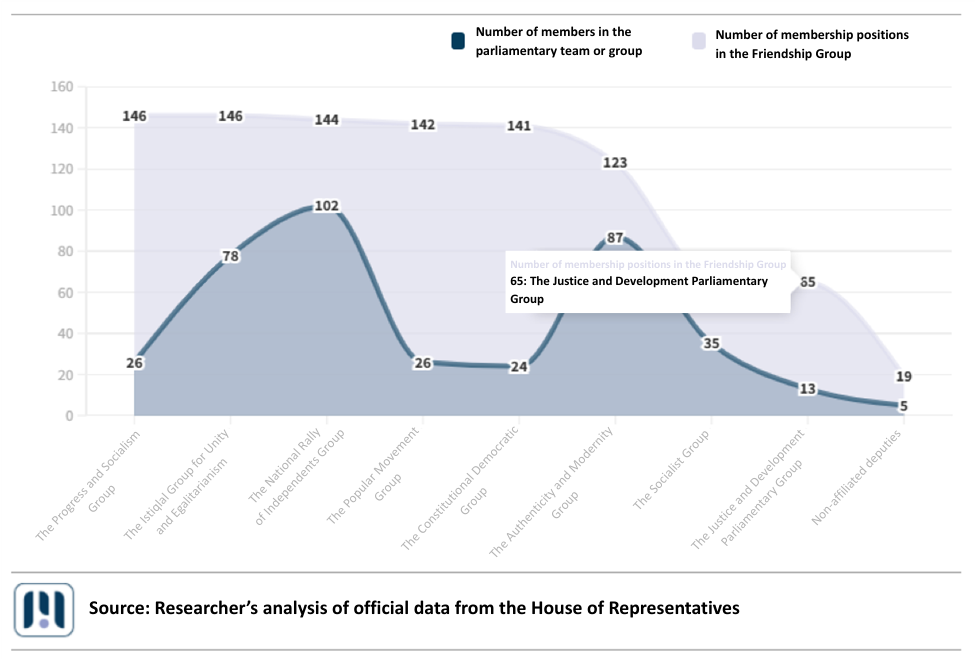

Figure (2): Members with the Highest Representation in Friendship and Fraternity Groups, by Political Affiliation

An analysis of data on the friendship and fraternity groups reveals a noticeable variation in Members’ engagement with this critical mechanism of parliamentary diplomacy. While Members of the Party of Progress and Socialism are the most active—each Member serving, on average, in seven different groups—it is striking that Members of the ruling majority have the lowest participation, generally belonging to only one or two groups at most.

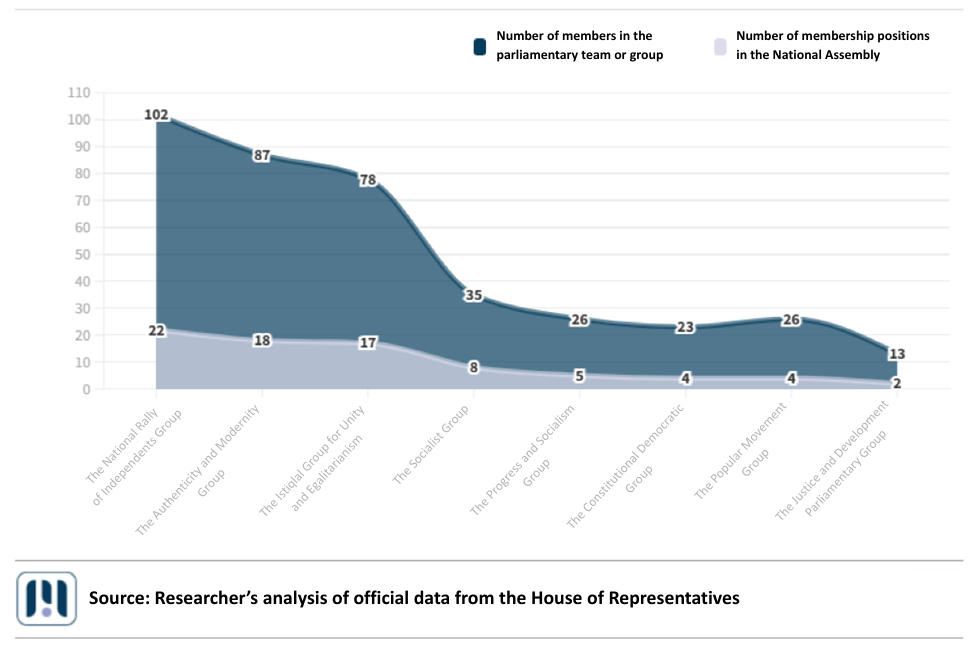

Regarding the Permanent National Delegations

Since the start of the current legislative term, 19 permanent national delegations have been formed, comprising a total of 80 Members who represent the House in international and regional parliamentary organizations. The data indicate that 71% of these delegates belong to majority groups: 22 are from the National Rally of Independents Group, 18 are from the Authenticity and Modernity Group, and 17 are from the Istiqlal Group for Unity and Egalitarianism—collectively exceeding the government majority’s proportional representation in the House of Representatives by about four percentage points.[15]

Ranking fourth is the Socialist–Federal Opposition Group with eight seats, followed by the Party of Progress and Socialism Group with five seats. Both the Constitutional Democratic and Social Group and the Popular Movement Group hold four seats each, while the Justice and Development Parliamentary Group has two seats.

Figure (3): Members with the Highest Representation in the Permanent National Delegations, by Political Affiliation

Key Actors

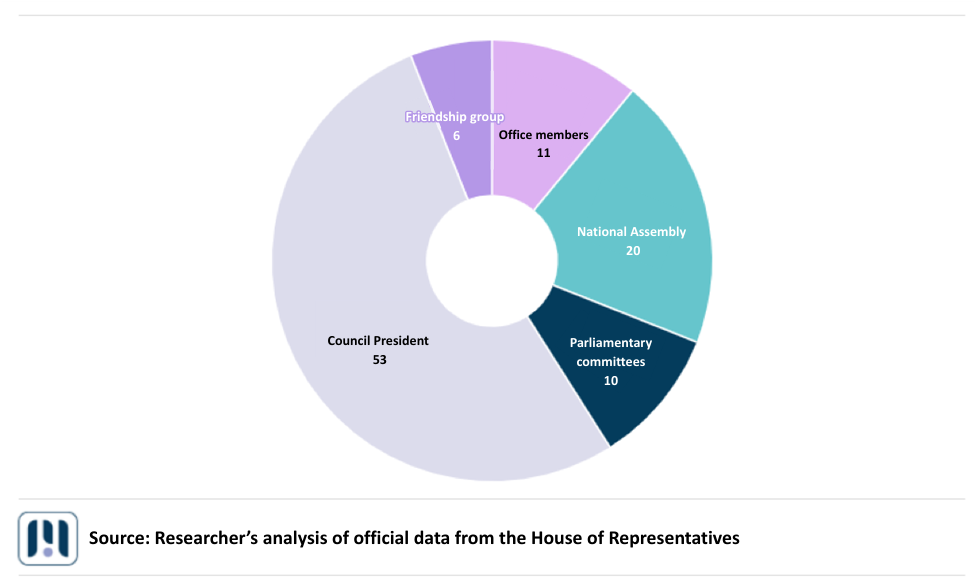

An analysis of the available data on the 495 diplomatic activities of the House of Representatives reveals the main players in this area, foremost among them the Bureau of the House, represented by the Speaker, the Deputy Speakers, and the House Secretary. At the top of the list stands the Speaker, accounting for 53% of all parliamentary diplomatic activities. Including the diplomatic activities overseen by the Deputy Speakers and the House Secretary brings the proportion for the House Bureau as a whole to 73% of all diplomatic activities, while the remaining 27% is split among other actors (the permanent national delegations, friendship and fraternity groups, and the standing committees).

Figure (4): Key Actors in Parliamentary Diplomacy (October 2021 – July 2024)

Friendship and fraternity groups—one of the most important mechanisms of parliamentary diplomacy—play only a modest role, accounting for 6% of all the House of Representatives’ diplomatic activities since the start of the current legislative term. In contrast, the proportion rises somewhat for the permanent national delegations: the total number of diplomatic activities in which members of these delegations were the main actors stands at 99, or approximately 20% of all diplomatic activities.

Areas of Engagement

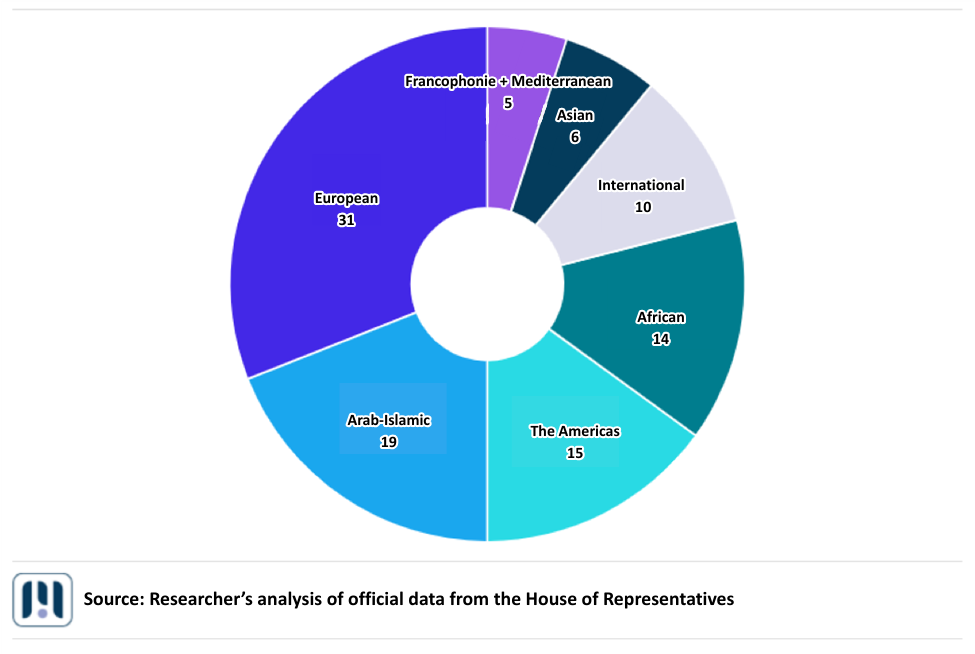

Parliamentary diplomacy has maintained its traditional areas of focus, even as it shows a clear trend toward expanding into new regions, notably through engagement with the parliaments of Latin America, the Caribbean, the Andean region, and the Central American Parliament. Meanwhile, Europe remains the arena that attracts the highest level of Moroccan diplomatic involvement, particularly through the Joint Parliamentary Committee between the Moroccan Parliament and the European Parliament, as well as the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

Figure (5): Percentage of the Most Active Parliamentary Diplomacy Arenas (October 2021 – July 2024)

Analysis of the data shows that 31% of the House of Representatives’ diplomatic activities took place in the European arena, followed by the Arab-Islamic sphere at 19%, then the Americas at 15%, Africa at 14%, the international arena at 10%, Asia at 6%, the francophonesphere at 3%, and finally the Mediterranean space at 2%.

Territorial Integrity

Given that safeguarding the Kingdom of Morocco’s territorial integrity is naturally the top priority for the parliamentary diplomacy of the House of Representatives, data indicate that 69 recorded activities—representing 14% of the total since the start of this legislative term through the end of July 2024—have resulted in an explicit stance supporting the Kingdom’s territorial integrity. Furthermore, the data show that 45% of the House’s diplomatic activities led to a position or decision aimed at strengthening or institutionalizing bilateral relations between Morocco and other parties—whether states or regional and international organizations. Meanwhile, 25% of these diplomatic activities were devoted to showcasing Morocco’s reforms and achievements in various fields.

Figure (6): Morocco’s Gains from the House of Representatives’ Diplomatic Activities

Multilateral parliamentary relations stand out for bringing new issues to the forefront of international discussions—ranging from climate and climate justice to advocacy on behalf of African countries in the Global South, among others. Moroccan advocacy around these issues—whether to express the Kingdom’s positions or to safeguard its interests—accounts for approximately 11% of all diplomatic activities undertaken by the House of Representatives. Notably, the gains made by the House’s parliamentary diplomacy during its first three legislative years include securing around 13 leadership positions within regional and international parliamentary organizations following the participation of Moroccan delegations in conferences and organizational meetings—occurrences that represent about 3% of the recorded diplomatic activities from the start of this term until the end of the second session of the third legislative year. During the same period, 8 Memorandums of Understanding were signed.

-

Challenges Ahead

Despite the requirements outlined in its internal regulations pertaining to Friendship and Fraternity Groups and Permanent National Delegations, the House of Representatives has not fully complied with these provisions. Three years into the current legislative term, the Permanent National Delegations have yet to produce any annual reports on their activities,[16] and the Friendship and Fraternity Groups have not developed the annual work plan they are supposed to submit to the Bureau for approval. Additionally, the Bureau itself has yet to establish specific rules regulating the work of these groups, hindering the attainment of their intended objectives.

A review of the King’s engagement with the topic of parliamentary diplomacy—from his accession to the throne until the opening of the legislative year in October 2024—and consideration of the data analyses concerning the House’s diplomatic activities reveal several challenges confronting parliamentary diplomacy. Chief among these are insufficient training, limited financial resources, and the dominance of ad hoc or situational practices.

Lack of Capacity Building

No concrete progress has been made in preparing Members of Parliament for their tasks in the realm of parliamentary diplomacy. This situation has persisted despite an April 2019 alert issued by the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council, which highlighted various obstacles to strengthening parliamentary diplomacy—most notably, the unaddressed need for better training for elected representatives.

In its report on “The Parliamentary Approach to the New Development Model for the Kingdom of Morocco,” the Council noted that the House of Representatives had devised a project “to enhance capacities in collaboration with the Diplomatic Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, though this project has yet to be implemented.”[17] Indeed, by the end of 2024, the initiative still had not materialized. The Minister of Foreign Affairs indicated that “the Diplomatic Academy is at the disposal of Members of Parliament to bolster their training,”[18] proposing “the availability of recognized diplomatic expertise to help support parliamentary diplomacy.”[19]

Given that the proportion of parliamentarians without a baccalaureate degree has risen from one-quarter in the previous legislative term to one-third in the current term (according to Ministry of the Interior data),[20] the question of Members’ fluency in foreign languages stands out as a major issue. This deficit represents a significant obstacle to making parliamentary diplomacy truly impactful, especially within Friendship and Fraternity Groups.

Parliamentary diplomacy demands skill sets enabling forceful and professional advocacy for Morocco’s strategic interests in international forums, in alignment with official diplomatic norms. Enhancing the effectiveness of parliamentary diplomacy and ensuring it becomes a sustained endeavor—rather than an occasional exercise—requires the House of Representatives to adopt a comprehensive training and capacity-building program for parliamentarians. This was underscored by the King in his most recent address to Parliament on October 11, 2024, when he urged Members to pursue a proactive role in parliamentary diplomacy through “strengthening human resource capacities and adopting competence-based criteria in selecting parliamentary delegations.”

Limited Resources

Financial and human resources play a vital role in supporting parliamentary diplomacy. When Members of Parliament and chairs of Friendship and Fraternity Groups were asked whether the House allocates any dedicated budget for their activities, they responded: “We have no information on this, nor has the House’s administration ever informed us of such a budget.”[21] Meanwhile, a member of the House Bureau observed that “it is not possible to open participation in diplomatic missions abroad to the chairs and members of Friendship Groups, due to limited financial resources.”[22]

A review of the House’s 2025 budgetary allocation reveals no specific funds for Friendship and Fraternity Groups to carry out their work. Although the House assigned 49.1 million dirhams for parliamentary diplomacy—representing 7.6% of its total budget—22% of that amount goes toward covering travel costs for Members and staff, 25% toward mission allowances abroad, and 29% toward lodging and catering expenses.[23] Given the modest outcomes achieved by parliamentary diplomacy, these figures raise questions about whether it amounts to “luxury tourism,” as the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council suggested in its 2019 report. In that analysis, the Council pointed out that “parliamentary diplomacy has not been sufficiently developed, has not attained its expected standing, and has not been allocated the requisite resources. In fact, it has sometimes been perceived as a form of luxury tourism.”[24]

Occasional Diplomacy and Official Dominance

Eleven years have passed since the King warned parliamentarians that they “only mobilize vigorously when there is an imminent threat to our territorial integrity, as though they await a signal before taking action.”[25] More than a decade on, this situation remains largely unchanged; the work of parliamentary diplomacy in the House of Representatives still appears mostly reactive. Most diplomatic activities consist of attending international and regional conferences, receiving foreign delegations at the House, or hosting events for international and continental parliamentary organizations.

A telling example is that the Speaker of the House is the primary actor in 53% of its diplomatic engagements—largely through participation in international conferences, receiving visiting parliamentary speakers and foreign ambassadors, or representing the King at various heads-of-state inaugurations. In this regard, a female Member of Parliament, who chairs a Friendship Group with an African country, noted that the Speaker, Rachid Talbi Alami, was forthright in a meeting, stating that financial resources are limited and do not allow for fully activating all parliamentary Friendship Groups. She added that the clear takeaway is that “the objective of these Friendship Groups is aligned with the circumstances Morocco faces and what official diplomacy, as managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, intends to achieve.”[26]

She went on to explain that official diplomacy largely delineates where and how parliamentarians can act to bolster parliamentary diplomacy. She remarked, “I have not convened any meeting of the Friendship Group I head. I am waiting for guidance from the House administration on any initiatives, based on our bilateral relations with the friendly country.”[27]

Although the House has, through parliamentary diplomacy, elicited statements of support for Morocco’s territorial integrity in about 14% of the total 495 diplomatic activities recorded during the first three years of this legislative term, these statements merely reaffirmed existing positions—they did not represent new breakthroughs or a major diplomatic gain. Consequently, the House of Representatives must develop a proactive parliamentary diplomacy strategy, setting clear objectives that enable significant gains in support of the national cause, as well as economic benefits by promoting investment opportunities in the Kingdom and building new partnerships.

Conclusion

Amid growing international support for Morocco on the Sahara issue, parliamentary diplomacy plays a pivotal role in securing strategic achievements and broadening supportive stances for the national cause. Yet current data indicate that the proportion of House-led diplomatic activities resulting in expressed support for Morocco’s territorial integrity stands at just 14% of the total 495 events during the first three years of the 2021–2026 legislative term—a figure that underscores a significant shortfall, given the high expectations placed on the legislative institution to defend the nation’s interests.

Although the Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives call for establishing parliamentary Friendship and Fraternity Groups and confer significant competencies upon them, the House continues to fall short of its mandate to invigorate parliamentary diplomacy, effectively stalling the tools at its disposal.

Parliamentary diplomacy should not be confined to occasional endeavors or reactive measures. Rather, it is a strategic and ongoing effort that demands continuity and meticulous planning. It is here that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’[28] initiative to launch a Diplomatic Academy takes on added significance, offering a crucial opportunity to train parliamentarians and equip them with the necessary diplomatic skills. By doing so, the legislature can develop a pool of competent representatives capable of addressing sensitive issues in international forums with both effectiveness and professionalism.

References

[1] – Royal speech dated October 11, 2024, delivered at the opening of the first session of the fourth legislative year of the eleventh parliamentary term. See the website of the Moroccan House of Representatives, available at: https://2u.pw/bVS1PAVk

[2] – Parliamentary diplomacy appeared in the late nineteenth century as a mechanism complementary to traditional diplomacy, following the founding of international organizations where the seeds of parliamentary diplomacy were sown—chief among them the Inter-Parliamentary Union, established in 1889, which is regarded as the first international organization aimed at promoting dialogue among parliaments.

[3] – As explained by French academic Philippe Péjo in a doctoral dissertation published by Université Paris-Saclay; see https://univ-droit.fr/recherche/actualites-de-la-recherche/parutions/35041-la-diplomatie-parlementaire

[4] – The “Soft Power” theory in the field of international relations was formulated by American scholar Joseph Nye in his 1990 book, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. The theory refers to the ability of states, institutions, or other actors to influence others or shape their preferences through attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or military force.

[5] – In a speech on October 14, 2016, the King stated: “The opening of the legislative year is a platform through which I simultaneously address the government, the parties, the various bodies and institutions, and the citizens.” See the text of the speech on the website of the Moroccan House of Representatives.

[6] – Published on the Parliament’s website: https://2u.pw/uemkJuBy

[7] – Referring to the period from 2015 to 2023.

[8] – Article 10 of the 2011 Constitution.

[9] – Internal Regulations of the House of Representatives, endorsed by the Constitutional Court on August 7, 2024, and published on the House’s website, available at: https://2u.pw/XWTXcbBg

[10] – Ibid.

[11] – Ibid.

[12] – Ibid.

[13] – The House of Representatives publishes its diplomatic activities in a dedicated section on its official portal; see https://2u.pw/zEtLjQO7

[14] – According to data published on the House of Representatives’ online portal.

[15] – The government majority comprises three parties: the National Rally of Independents (RNI), the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM), and the Istiqlal Party (PI). Together, they hold 267 seats—approximately 67% of the total 395 seats in the House of Representatives.

[16] – Article 312 of the House’s Internal Regulations stipulates that the Permanent National Delegations “shall prepare an annual report on their work, which shall be submitted to the Bureau of the House.” Seehttps://www.chambredesrepresentants.ma/sites/default/files/2024-09/RI2024F_0.pdf

[17] – Report by the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (under reference No. 24/2019), published on its official website, pp. 53–54, available at: https://2u.pw/bbAPHLnt

[18] – As stated by Nasser Bourita on November 8, 2024, before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, National Defense, Islamic Affairs, and Affairs of Moroccans Residing Abroad, during the presentation of his Ministry’s budget proposal for the 2025 fiscal year, p. 31.

[19] – Ibid.

[20] – According to a communiqué issued by the Ministry of the Interior to media outlets on September 26, 2021. See Al-3omk online news, available at: https://al3omk.com/684531.html

[21] – Research interviews with three chairs of parliamentary Friendship Groups.

[22] – Research interview with a member of the House Bureau.

[23] – Based on a presentation by the Speaker of the House of Representatives on November 8, 2024, regarding the draft sub-budget of the House, delivered to the Finance and Economic Development Committee of the House.

[24] – Report by the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council, previously cited, p. 54.

[25] – Speech by King Mohammed VI at the opening of Parliament on October 11, 2013.

[26] – Research interview conducted in January 2025 with a female Member of Parliament who chairs a Friendship Group.

[27] – Ibid.

[28] – Nasser Bourita’s presentation before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, previously cited, p. 31.

Yassir El Makhtoum

A Moroccan journalist recognized for their exemplary contributions to the field of journalism, having been awarded the Grand National Prize for Moroccan Journalism as well as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Prize for Specialized Journalism, specifically within the context of the Middle East and North Africa region.