[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Morocco’s experience in addressing the economic fallout from COVID-19 illustrates many of the economic challenges that middle-income countries are facing and the fiscal limitations they confront.

Middle-income countries within and beyond the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) adopted strong security responses early on, which helped in mitigating the public health threat at the onset of the coronavirus outbreak. However, confronted with heightened economic hardship, these countries gradually relaxed precautionary measures and must now control the epidemiological situation, while attempting to rebuild their economies and provide social welfare to their citizens. Morocco’s experience in addressing the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic illustrates many of the economic challenges that middle-income countries are facing, and the fiscal limitations they confront that wealthier countries do not have to bear.

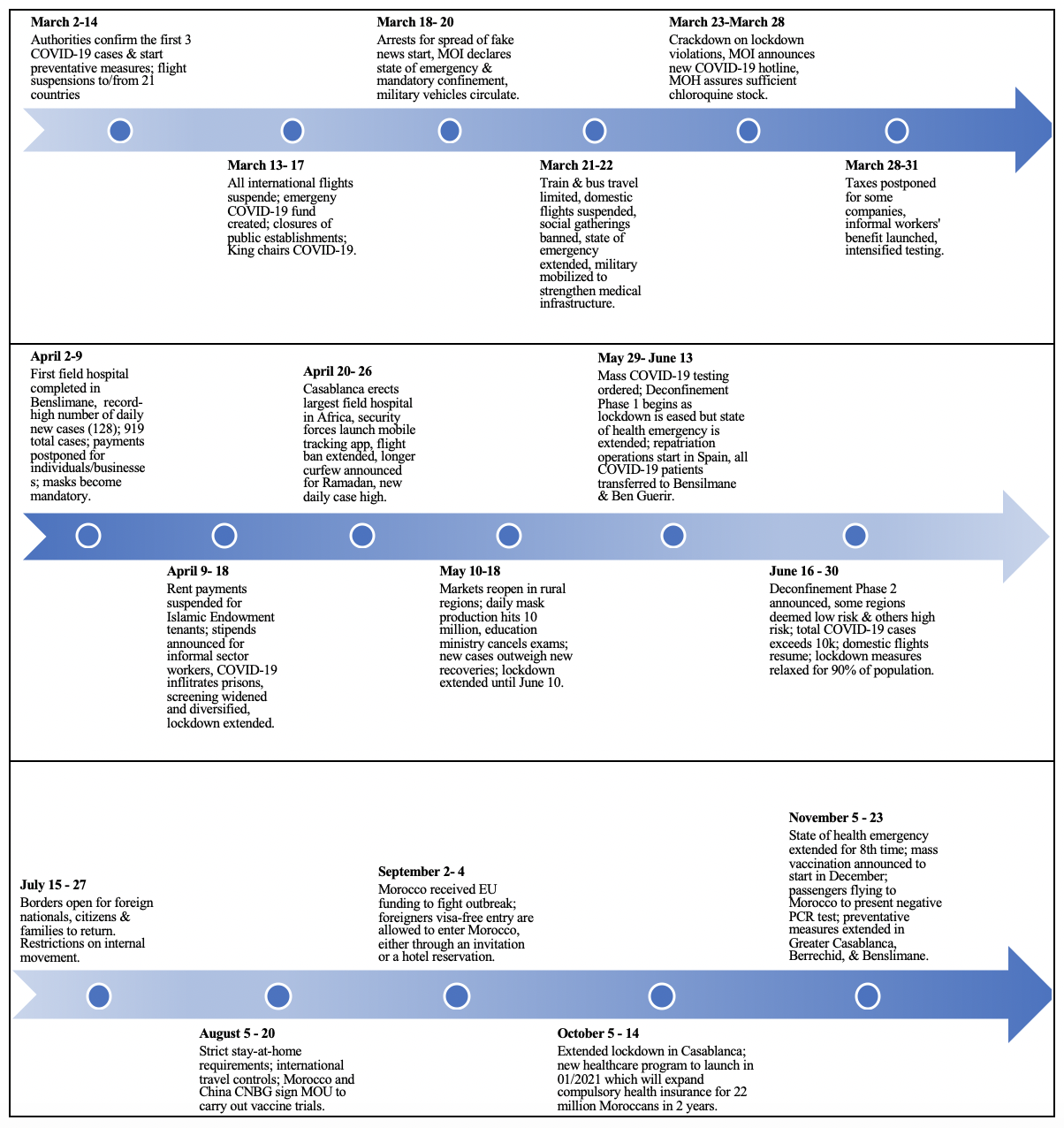

Currently one of the MENA’s most impacted countries by the coronavirus pandemic in terms of contaminations and deaths, Morocco had initially successfully controlled the outbreak between March and May 2020 after declaring a national health emergency, closing its borders, and calling for mandatory confinement (see Figure 1). However, the state’s priorities shifted as the pandemic, and the associated lockdown strategy, resulted in economic loss. As a result, Moroccan decisionmakers relaxed precautionary measures in June 20 in favor of relaunching the economy and alleviating the financial burdens of citizens and businesses (see Figure 2).

How did the Moroccan regime address the massive economic impact of the global pandemic, what were the strengths and weakness of its strategy, and what challenges will it face when attempting to recover the economy following what will likely be a deep recession?

Figure 1: Timeline of Government COVID-19 Response in Morocco (March- November 2020)

Source: MEED, “Latest on the Region’s Covid-19 Recovery,” November 24, 2020, www.meed.com/latest-news-on-the-pandemics-economic-impact; Safaa Kasraoui, “Coronavirus Pandemic: A Timeline of COVID-19 in Morocco,” Morocco World News, March 19, 2020, www.moroccoworldnews.com/2020/03/296727/coronavirus-a-timeline-of-covid-19-in-morocco.

Figure 2:Stringency of Morocco’s COVID-19 response against daily cases

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Our World in Data.

Note: On the Stringency Index, 100 represents the strictest approaches to closures. Daily new cases have been smoothed using a running average.

COVID-19’s economic impact on Morocco

Morocco’s macroeconomic balances were predictably negatively impacted by the containment measures and reduced global demand resulting from the pandemic, as well as by a harsh drought and a drop in major exports. Indeed, the trade deficit has widened by 23.8 percent in the first quarter of 2020; while economic growth receded by 1.1 percent in the first quarter of 2020, and 1.8 percent in the second quarter. Because of a breakdown in their supply chains and the disruption of tourism, most major export sectors have been impacted (automotive, aeronautics, textile etc.); in fact, exports dropped by 19.7 percent between January and April, 2020. Imports, on the other hand, are expected to increase. The kingdom is expected to conclude 2020 with an economic contraction of 6.6 percent.

Furthermore, the pandemic, and associated lockdown measures, led to a significant increase in unemployment and underemployment. In fact, national unemployment rates, which are projected to reach their highest levels since 2001, increased from 9.1 percent in 2019 to 13 percent in 2020. In urban areas, the unemployment rate reached 15.6 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (compared to 13.1 percent in 2019); in rural areas, it increased from 3.4 percent in 2019 to 7.2 percent in 2020. For young people aged 24 to 35 years specifically, this number reached a record-high of 22.6 percent.

In terms of numbers of jobs lost, this translates to an estimated 581,000 jobs lost year-on-year during the third quarter of 2020, most of which were in rural areas. In the informal sector, which accounted for an estimated 20 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), around five million workers became unemployed since the start of the pandemic. In addition, working hours decreased on average from 46 to 22 hours per week (i.e., 265 million less weekly working hours in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the same timeframe in 2019).

Companies were also harshly affected by the pandemic; 142,000 companies (i.e., 57 percent of those registered) declared suspending operations (135,000 temporarily and 6,300 altogether); 72 percent of these were micro-sized. Significantly, one of the worst-hit sectors, tourism, is also one of the sectors Morocco’s economy depends on the most, and is projected to account for 6.4 percent of GDP. This sector may see up to $14 billion in losses between 2020 and 2022. The percentage of companies that suspended activities in the closely related hospitality sector reached 89 percent.

Alleviating economic pressures

Similar to other middle-income countries, Morocco’s COVID-19 economic strategy aimed to support economically vulnerable citizens and businesses (through aid, repayment plans, and loan packages), increase healthcare spending, and ensure liquidity provision. However, fiscal limitations meant that relief packages were smaller than in wealthier countries (see Figure 3). Despite these limitations, significant steps were taken, starting with the creation of a taskforce to help the Ministry of Economy and Finance monitor the economic impact of the pandemic. The regime also created an emergency fund in mid-March to help with COVID-related expenses; this fund raised the equivalent of $3.2 billion as of end of April 2020.

Furthermore, after a national lockdown was implemented in March, the government pledged stipends for all workers who lost jobs or working hours due to the pandemic. Formal sector employees would receive the equivalent of $220 per month, and those in the informal sector would receive between $90 to 134 per month, depending on family size. However, there were notable issues surrounding these stipends. First, distributing the pledged aid to all affected employees across the country did not happen in a regular and consistent manner; delays and missed payments took place.[1] Second, while helpful, the amount of aid provided was not sufficient to cover the basic needs of many people (rent, subsistence, etc.).

Businesses also received help; the central bank reduced the benchmark lending rate, increased refinancing operations for small businesses, and expanded the range of collateral to include public and private debt instruments. Furthermore, small businesses received tax deferments, while both small and medium businesses were entitled to three-month loan repayment suspensions and interest free loans. Indeed, as of May 2020, 9,000 loans (the equivalent of $370 million) were given to companies with a turnover below $50 million, though the newly founded guarantee program Damane Oxygene. Self-employed individuals affected by the COVID-19 crisis benefitted from interest-free loans of up to $1,500.

Figure 3: Fiscal support in response to COVID-19: Limited policy space constrained many More Developed Countries (MDC). (percent of GDP)

Economic Recovery Outlook

Resource-poor Morocco’s fiscal realities limit and complicate the regime’s response to the massive economic consequences of the global pandemic. Indeed, beyond the far-reaching impacts of COVID-19, the kingdom’s already frail economy was further harmed by a draught and a major drop in exports in 2020. In light of this, any economic recovery strategy will be undermined by Morocco’s underlying lack of resources; the regime does not have the wealth or solid economic structures required to deal with the pandemic.

The Central Bank has concluded that the outlook for Morocco’s economic development in 2021 and 2022 is uncertain. However, the last quarter of 2020 has been marked by government level discussions about how economic recovery might be approached in the near future. In October, the king announced a roadmap to revive the country’s economy with the help of a major universal social security project which will reform public establishments.[1] Another main focus will be determining how to revive and prioritize key sectors that were harshly affected in 2020, such as tourism, transport, hospitality, and the private sector.

Several major challenges remain. First, since Morocco’s main trading partner, the European Union, is likely to face a recession, trade is unlikely to bounce back immediately. Second, while reducing the national unemployment rate in 2021 is necessary, this is something the regime has struggled with for decades and is unlikely to solve in the near future. Finally, banking on the tourism sector to accelerate economic recovery will lead to disappointing results. Given travel difficulties associated with the global pandemic, international tourism will continue to plummet, while domestic tourism will be limited due to citizens’ economic hardship.

In the short-term, as COVID-19 cases continue to rise, and as the Moroccan regime attempts to strike a balance between recovering the economy and saving lives, Morocco is banking on Chinese laboratory Sinopharm’s vaccine to pave the way for economic recovery. In the meantime, the regime must invest more in reforming the social coverage system as it does not have enough resources to deal with the economic fallout of such crises. Indeed, the economic management of the crisis has shown that there are difficulties linked to the narrowness of the tax base which jeopardizes the state’s budgetary margins and its ability to adopt countercyclical policies.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Yasmina Abouzzohour

A visiting fellow at Brookings, Abouzzohour holds a PhD in Politics from the University of Oxford where she taught comparative politics, international relations, and economic governance. Her research focuses on authoritarian persistence and transition, strategic regime behavior and interactions with opposition movements, and mixed methods research. She is currently writing a book on regime survival in MENA monarchies and completing several projects on the politics and economy of North African states. Abouzzohour previously worked as a Political Risk Analyst at Oxford Analytica and holds a B.A. (Hons) in Political Science from Columbia University.