[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Despite 21 years of socio-economic achievements, deeply-rooted challenges persist in Morocco

July 30, 2020 marks the 21st anniversary of King Mohammed VI’s ascension to the Moroccan throne. Throughout his reign, several mega-projects, a foreign policy re-direction, and infrastructural change have boosted the kingdom’s economy and set the stage for future international investment and cooperation. Yet, although some macro-economic and social indicators point to an improved socio-economic landscape, the country continues to suffer from deeply rooted socio-economic problems- including high unemployment rates, towering public debt, overreliance of a fickle agricultural sector, social inequality, and a persistent urban-rural divide. These problems, which have fueled discontent in recent years, will be exacerbated by the far-reaching economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic, and may lead to future contestation.

Achievements

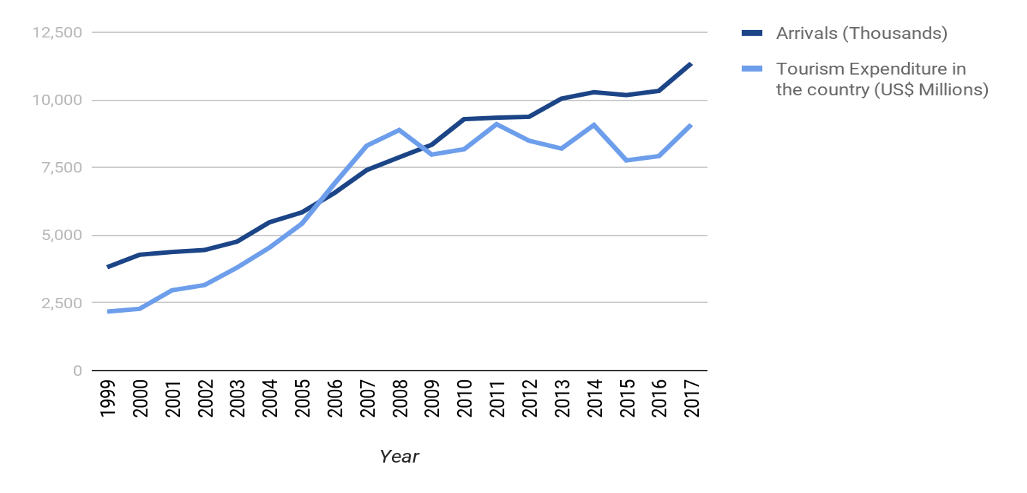

Since Mohammed VI’s ascension to the throne in 1999, there has been significant improvement in terms of macro-economic indicators. Between 1999 and 2019, exports tripled,[1] per capita income (constant dollars over time) increased from USD 1,963 to USD 3,361,[2] and total unemployment decreased from 13.9 percent to 9 percent (see Figures 1 and 2).[3] Available poverty data show that, between 2000 and 2013, the poverty headcount ratio at the national poverty lines decreased from 15.3 percent to 4.8 percent.[4] Furthermore, a strong revival of the tourism sector boosted the economy. Over the last two decades, the number of tourists visiting Morocco tripled (see Figure 3).[5] In fact, from 2000 to 2018, the country recorded an average annual growth of 6 percent in tourism arrivals; this is two points higher than growth in global tourism.[6]

Figure 1: GDP Indices, 1999-2018

Source: World Bank, Morocco “GDP per capita (current US$),” and “GDP (current US$ 10 Millions),” retrieved on July 30, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

Figure 2: Morocco National Unemployment Rate and Annual Change (1999-2020)

Source: World Bank Unemployment Data, accessed via Macro Trends, retrieved on July 30, 2020, <a href=’https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MAR/morocco/unemployment-rate’>Morocco Unemployment Rate 1991-2020</a>. www.macrotrends.net.

Figure 3: Inbound Tourism and Expenditure, 1999-2017

Source: World Tourism Data, “Arrivals of non-resident tourists/visitors” and “tourism expenditure,” Retrieved July 30, 2020, http://data.un.org/DocumentData.aspx?q=tourism&id=409#19.

In terms of social indicators, between 1999 and 2019, primary school enrollment rate increased by over 27 points,[7] and life expectancy increased by over eight years. [8] Furthermore, massive infrastructural development took place as the regime pushed for mass electrification and moved to improve the country’s motorway infrastructure. [9] Between 1999 and 2016, the motorway network’s length was extended from around 400 kilometers to 1,831 kilometers.[10] This upgraded network gives 60 percent of the population (mostly in urban areas) direct access to the highway network;[11] and it connects 18 airports and 37 commercial ports (13 of which are dedicated to foreign trade).[12]

Morocco’s foreign policy re-direction[13] under the current king has benefited the economy as Mohammed VI diversified the kingdom’s alliance base by rejoining the African Union (AU) in 2017 [14] and by improving relations with Europe.[15] Indeed, over the last two decades, Morocco has preserved a strong relationship with the European Union (EU) which allowed it to receive EU bilateral aid and to maintain trade relations with Europe. The latter, Morocco’s largest trading partner and donor, accounted for 59.4 percent of Morocco’s trade in 2017- specifically, 64.6 percent of its exports and 56.5 percent of its imports (see Figure 4).[16] At least 73 percent of Morocco’s inward foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks in 2019 came from European countries.[17]

Figure 4: EU-Morocco Trade Flows and Balance (2008-2018)

Source: European Commission, “ European Union, Trade in goods with Morocco,” Retrieved July 30, 2020, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_morocco_en.pdf

Mohammed VI’s move to champion greater Moroccan presence within the African continent also benefited Morocco’s economy as it encouraged Moroccan companies to increase cooperation with sub-Saharan Africa in banking, telecommunications, insurance, and manufacturing. [18] In fact, 85 percent of the kingdom’s FDI went to sub-Saharan states in 2018.[19] Trade with the continent increased by 68 percent between 2008 and 2018 (see Figure 5);[20] and Moroccan exports to western Africa tripled during the same period.[21] Furthermore, beyond boosting the kingdom’s economy and diversifying its alliance base, Morocco’s re-direction towards Africa enhanced the country’s international standing, shored up its regional support, and benefited its relationship with the EU by opening up the possibility of Morocco-EU-African trade.

Figure 5: Annual change in total trade volume with Morocco (%), 2008-18

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) Database, “Morocco Import in thousand US$ all regions between 1993 and 2018,” accessed June 26, 2020, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/MAR/StartYear/1993/EndYear/2018/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/BY-REGION/Indicator/MPRT-TRD-VL#; WITS Database, “Morocco Export in thousand US$ all regions between 1993 and 2018,” accessed June 26, 2020, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/MAR/StartYear/1993/EndYear/2018/TradeFlow/Export/Partner/BY-REGION/Indicator/XPRT-TRD-VL.

Finally, Mohammed VI’s reign saw the completion of two mega-projects: a solar complex and a high-speed train. The country’s first mega solar power complex, Noor, will be the world’s largest concentrated solar power plant,[22] and will be able to power a city twice the size of Marrakech at peak capacity.[23] It will eventually reduce Morocco’s reliance on energy imports, the aim being for 42 percent of Morocco’s electrical power to come from renewable sources by 2020 and 52 percent by 2030.[24] Funded at around USD 9 billion,[25] most of Noor’s phases are already on stream (and construction is underway for the final phase).[26]

The first phase of Morocco’s high-speed rail service, Al Boraq, was inaugurated in November 2018. It currently spans close to 350 kilometers, connecting Casablanca and Tangier and reducing the travel time between them from five hours to two hours. The plan is for the high-speed rail service to extend to 1,500 kilometers throughout the country.[27] By investing in such a high cost project (funded at USD 2 billion)[28] the regime aims to attract greater investment and tourism inflow.

Challenges

Despite these achievements, Morocco faces persistent socio-economic challenges. The country continues to suffer from towering public debt which reached USD 76.8 billion in 2019, which is 65.0 % of the country’s nominal GDP. [29] An oil and gas importer, Morocco imported 76.4 billion dirhams’ worth of energy resources (around USD 8 billion)[30] in 2019, which represented 15.6 percent of its total import bill and made it the largest energy importer in North Africa. Morocco’s reliance on oil imports makes it vulnerable to oil’s boom-and-bust cycle, pressuring its economy every time oil prices peak.

Morocco relies on unstable sectors- most notably agriculture and tourism- which makes it vulnerable to exogenous shocks such as weather conditions, global economic crises, pandemics etc. Indeed, the agricultural sector accounted for approximately 39 percent of total employment in 2018;[31] while the tourism sector represented 7 percent of the country’s economic activity in 2019, generated USD 8 billion in foreign currency inflows, and employed around 750,000 people.[32]

Inequality remains a pressing issue due to the country’s wide center-periphery wealth divide and the state’s failure to close the gap between the highest and lowest socio-economic classes. With its Gini index standing at 40.9 percent in 2019- meaning it has barely improved since 1998-[33] Morocco is the North African country with the highest inequality score (excluding war-stricken Libya).[34] In 2018, OXFAM reported that a Moroccan on minimum wage (MAD 2,570.86 or around USF 250 per month in 2018) would need over 150 years to earn as much as a billionaire does in one year, while the estimated wealth of three Moroccan billionaires 4.5 billion was more than that of 375,000 of the poorest Moroccans.[35]

Furthermore, while nearly a quarter of citizens are poor or at risk of poverty according to the World Bank,[36] Moroccans living in rural areas are more affected. Indeed, the rural population accounted for 79.4 percent of poor people in the country in 2018, twice as high as at the national level.[37] Urban populations face economic hardship as well, especially urban youths who struggle with high levels of unemployment (see Figure 6). In 2019, Morocco’s youth unemployment rate reached 22% nationally and 40.3% in urban areas.[38] These numbers are even more significant when considering that 16.6 percent of the population consists of young people (ages 15 to 24).[39]

Figure 6: Morocco Youth Unemployment Rate and Annual Change (1999-2020)

Source: World Bank Unemployment Data, accessed via Macro Trends, retrieved on July 30, 2020, <a href=’https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MAR/morocco/youth-unemployment-rate’>Morocco Youth Unemployment Rate 1991-2020</a>. www.macrotrends.net.

Conclusion

Protests in recent years have been triggered, at least in part, by tough economic conditions, including the 2011 uprisings, the 2016-2018 Rif upheaval, protests in Jrada and Errachidia, and various scattered manifestations throughout 2019.[40]This trend will likely continue. As economic hardship persists for marginalized communities and popular frustration grows due to persistent social inequality, discontent will increase, and protests will likely multiply. The economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic (due to disrupted trade flows, reduced tourism, population lockdown, a potential European crisis, and increased public spending) will exacerbate the situation. Regional mobilization, such as the Hirak movement in neighboring Algeria and the protests movement in Lebanon, will embolden Moroccans to express dissent. The regime must act fast to reduce social inequality and improve the country’s economic landscape in the long-term. Although high public debt and dependency on oil imports have limited available state funding, the regime still has several options available, including improving the tax collection system; spending less on mega-projects; and reforming the country’s taxation policy.

Read more here: https://www.brookings.edu/research/progress-and-missed-opportunities-morocco-enters-its-third-decade-under-king-mohammed-vi/

Endnotes

[1] World Bank Statistical Database, “Exports of goods and services (constant 2010 US$) – Morocco,” accessed January 4, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.KD?locations=MA.

[2] World Bank Statistical Database, “GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$) – Morocco,” accessed January 4, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=MA.

[3] World Bank Statistical Database, “Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) – Morocco,” accessed September 25, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=MA.

[4] World Bank Statistical Database, “Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) – Morocco,” accessed September 25, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?locations=MA.

[5] United Nations Data, “Arrivals of nonresident tourists/visitors, departures and tourism expenditure in the country and in other countries,” accessed May 4, 2020, http://data.un.org/DocumentData.aspx?id=409.

[6] https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/01/264155/tourists-morocco/

[7] World Bank Statistical Database, “Adjusted net enrolment rate, primary (% of primary school age children) – Morocco,” accessed September 25, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.TENR?locations=MA.

[8] World Bank Statistical Database, “Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Morocco,” accessed September 25, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=MA.

[9] World Bank Statistical Database, “Access to electricity, rural (% of rural population), Access to electricity, urban (% of urban population),” accessed September 30, 2019, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG&country=#.

[10] “Chiffres clés: Dates clés” [Key figures: Key dates], Autoroutes du Maroc, accessed May 20, 2020, https://www.adm.co.ma/adm/Chiffres-cles/Pages/dates-cles.aspx.

[11] Agence France-Presse, “20 ans de règne. L’analyse de 2 conseillers du roi et de 2 anciens ministres” [20 years of reign. Analysis of two king’s advisers and two former ministers], Les Inspirations Éco, July 31, 2019, https://leseco.ma/20-ans-de-regne-l-analyse-de-2-conseillers-du-roi-et-de-2-anciens-ministres/.

[12] Ibid; Agence Ecofin, “Maroc : 20 ans de règne de Mohammed VI en 10 chiffres clés” [Morocco: 20 years of Mohammed VI’s reign in 10 key figures], July 28, 2019, https://www.agenceecofin.com/gouvernance/2807-68234-maroc-20-ans-de-regne-de-mohammed-vi-en-10-chiffres-cles.

[13] Mohamed Karim Boukhssass, “Yasmina Abouzzohour: al-Maghrib ‘abbara biwuduh ’anahu la yumkin ’an yakuna tahta wisayati ’ahadin wa la yumkin ’ibtizazuhu limawaqifihi,” [Morocco has clearly stated that it cannot be under the guardianship of anyone and cannot be blackmailed for its positions], Al Ayam no. 840 (February 14–20, 2019), https://mipa.institute/6525.

[14] Nizar Manek, “Morocco Rejoins African Union Three Decades After Withdrawal,” Bloomberg, January 31, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-31/morocco-rejoins-african-union-three-decades-after-withdrawal.

[15] Yasmina Abouzzohour and Beatriz Tomé-Alonso, “Moroccan foreign policy after the Arab Spring: a turn for the Islamists or persistence of royal leadership?,” The Journal of North African Studies 24, no. 3 (2019): 444–67, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13629387.2018.1454652.

[16] “Morocco Trade Picture,” European Commission, accessed May 21, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/morocco/index_en.htm.

[17] Author’s calculations based on data from “Recettes des investissements directs étrangers au Maroc: Repartition par pays et organisme financier” [Receipts from foreign direct investments in Morocco: Breakdown by country and financial institution], Office des Changes, accessed June 26, 2020, https://www.oc.gov.ma/fr/etudes-et-statistiques/series-statistiques. The countries included in the author’s calculations are the following: Ireland, France, Denmark, Spain, Luxembourg, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Cyprus, Germany, Malta, Italy, Greece, Portugal, Poland, Austria, Norway, and Sweden.

[18] “HM the King Delivers Speech to Nation on 44th Anniversary of Green March,” Agence Marocaine de Presse, accessed May 20, 2020, http://www.mapnews.ma/en/discours-messages-sm-le-roi/hm-king-delivers-speech-nation-44th-anniversary-green-march.

[19] “Banking on ECOWAS: Why Morocco is cosying up to sub-Saharan Africa,” The Economist, July 19, 2018, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/07/19/why-morocco-is-cosying-up-to-sub-Saharan-africa.

[20] “Moroccan-Sub-Saharan Trade Increased by 9.1% in 2016: Foreign Exchange Office,” Morocco World News, July 15, 2017, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2017/07/223214/moroccan-sub-Saharan-trade-increased-by-9-1-in-2016-foreign-exchange-office/.

[21] “Banking on ECOWAS.”

[22] Tarik Bouhal et al., “Technical feasibility of a sustainable Concentrated Solar Power in Morocco through an energy analysis,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 81, no. 1 (January 2018): 1087–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.056.

[23] “Morocco Reaps Benefits of King’s Energy Farsightedness,” The North Africa Post, July 16, 2019, https://northafricapost.com/32543-morocco-reaps-benefits-of-kings-energy-farsightedness.html.

[24] The World Bank, “Implementation Completion and Results Report on a Loan in the Amount of US$200 Million, Loan Number 80880-MA, and a Clean Technology Fund Loan in the Amount of US$97 Million, Loan Number TF010916, to the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy for the Ouarzazate Concentrated Solar Power Project ( P122028 ),” Report No. ICR00004271, March 31, 2018, http://documents.banquemondiale.org/curated/fr/503371525382384008/pdf/ICR4271-PUBLIC-3-29-18.pdf.

[25] Hamza Hamouchene, “The Ouarzazate solar plant in Morocco: Triumphal ‘Green’ capitalism and the privatization of nature,” Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt, March 25, 2016, https://www.cadtm.org/The-Ouarzazate-solar-plant-in; Reuters, “Vast Moroccan Solar Power Plant is Hard Act for Africa to Follow,” Fortune, November 5, 2016, https://fortune.com/2016/11/05/moroccan-solar-plant-africa/.

[26] “Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex,” Power Technology, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.power-technology.com/projects/noor-ouarzazate-solar-complex/.

[27] “La LGV en chiffres” [The high-speed rail in numbers], Libération, November 16, 2018, https://www.libe.ma/La-LGV-en-chiffres_a103324.html.

[28] Ahlam Ben Saga, “Politician Omar Balafrej Says LGV Train is Not a Priority for Morocco,” Morocco World News, November 15, 2018, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2018/11/257768/omar-balafrej-lgv-train-not-priority-morocco/; David W. Smith, “Morocco’s €1.8 billion TGV project splits opinion,” Construction Shows, October 31, 2011, https://www.constructionshows.com/moroccos-e1-8-billion-tgv-project-splits-opinion/.

[29] “Morocco Government Debt: % of GDP,” CEIC Data, accessed December 16, 2019, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/morocco/government-debt–of-nominal-gdp.

[30] Youssef Boudlal, “Morocco’s trade deficit widens by 1.5% in 2019,” Reuters, February 5, 2020, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/moroccos-trade-deficit-widens-by-1.5-in-2019-2020-02-05

[31] Danish Trade Union Development Agency, “Labour Market Profile 2018: Morocco,” Labour Market Profile, January 2018, https://www.ulandssekretariatet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Marocco_lmp_2018.pdf; “The World Factbook – Morocco,” Central Intelligence Agency, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mo.html.

[32]Ahmed Eljechtimi, “Morocco hopes to boost domestic tourism to save key sector,” Reuters, May 13, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-morocco-tourism/morocco-hopes-to-boost-domestic-tourism-to-save-key-sector-idUSKBN22P2Q8; Yahia Hatim, “Nearly 13 Million Tourists Visited Morocco in 2019,” Morocco World News, February 3, 2020, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2020/02/292688/nearly-13-million-tourists-visited-morocco-in-2019/.

[33] The Gini index measures the distribution of income across income percentiles in a population. A higher score indicates greater inequality. “Gini Coefficient by Country 2020,” World Population Review, accessed May 20, 2020, http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/gini-coefficient-by-country/; World Bank Statistical Database, “GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Morocco,” accessed May 21, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=MA.

[34] “Gini Coefficient by Country 2020.”

[35] “Un Maroc égalitaire, une taxation juste.” OXFAM Reports, April 29, 2019, https://www.oxfamfrance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Rapport-Oxfam-2019-Un-Maroc-égalitaire_une-taxation-juste.pdf.

[36] Marie Anne Chambonnier, “Macro Poverty Outlook: Morocco,” The World Bank, 2019, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/234641554825526725/mpo-mar.

[37] The World Bank, “Morocco Digital and Climate Smart Agriculture Program (P170419): Program Information Document (PID),” Report No. PIDC190843, July 28, 2019, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/648291567624827368/pdf/Concept-Stage-Program-Information-Document-PID-Morocco-Digital-and-Climate-Smart-Agriculture-Program-P170419.pdf.

[38] World Bank Statistical Database, “Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15-24) (modeled ILO estimate) – Morocco,” https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SL.UEM.1524.ZS&country=MAR; Katya Schwenk, “Despite Accelerated Growth, Unemployment Persists in Morocco,” Morocco World News, June 5, 2019, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/06/275140/acceleration-growth-unemployment-morocco-industries/.

[39] “The World Factbook – Morocco.”

[40] Ahmed Eljechtimi, “Moroccan economy falls short of meeting social demands, central bank says,” Reuters, July 29, 2019, https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL8N24U5L6; “Morocco: Hundreds of teachers protest in demand for higher wages,” Middle East Monitor, October 7, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20191007-morocco-hundreds-of-teachers-protest-in-demand-for-higher-wages/; Reuters, “Thousands of Moroccan teachers protest over pay,” France 24, March 24, 2019, https://www.france24.com/en/20190324-thousands-moroccan-teachers-protest-over-pay-rabat-education; “Moroccan police crack down on protesting teachers,” Al Jazeera, February 20, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/02/moroccan-police-crack-protesting-teachers-190220173941088.html.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Yasmina Abouzzohour

A visiting fellow at Brookings, Abouzzohour holds a PhD in Politics from the University of Oxford where she taught comparative politics, international relations, and economic governance. Her research focuses on authoritarian persistence and transition, strategic regime behavior and interactions with opposition movements, and mixed methods research. She is currently writing a book on regime survival in MENA monarchies and completing several projects on the politics and economy of North African states. Abouzzohour previously worked as a Political Risk Analyst at Oxford Analytica and holds a B.A. (Hons) in Political Science from Columbia University.