[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The epidemiological situation will continue to deteriorate at multiple levels. This is evidenced in the ever-rising number of cases, which reinforces fears of the collapse of the national health system.

Introduction

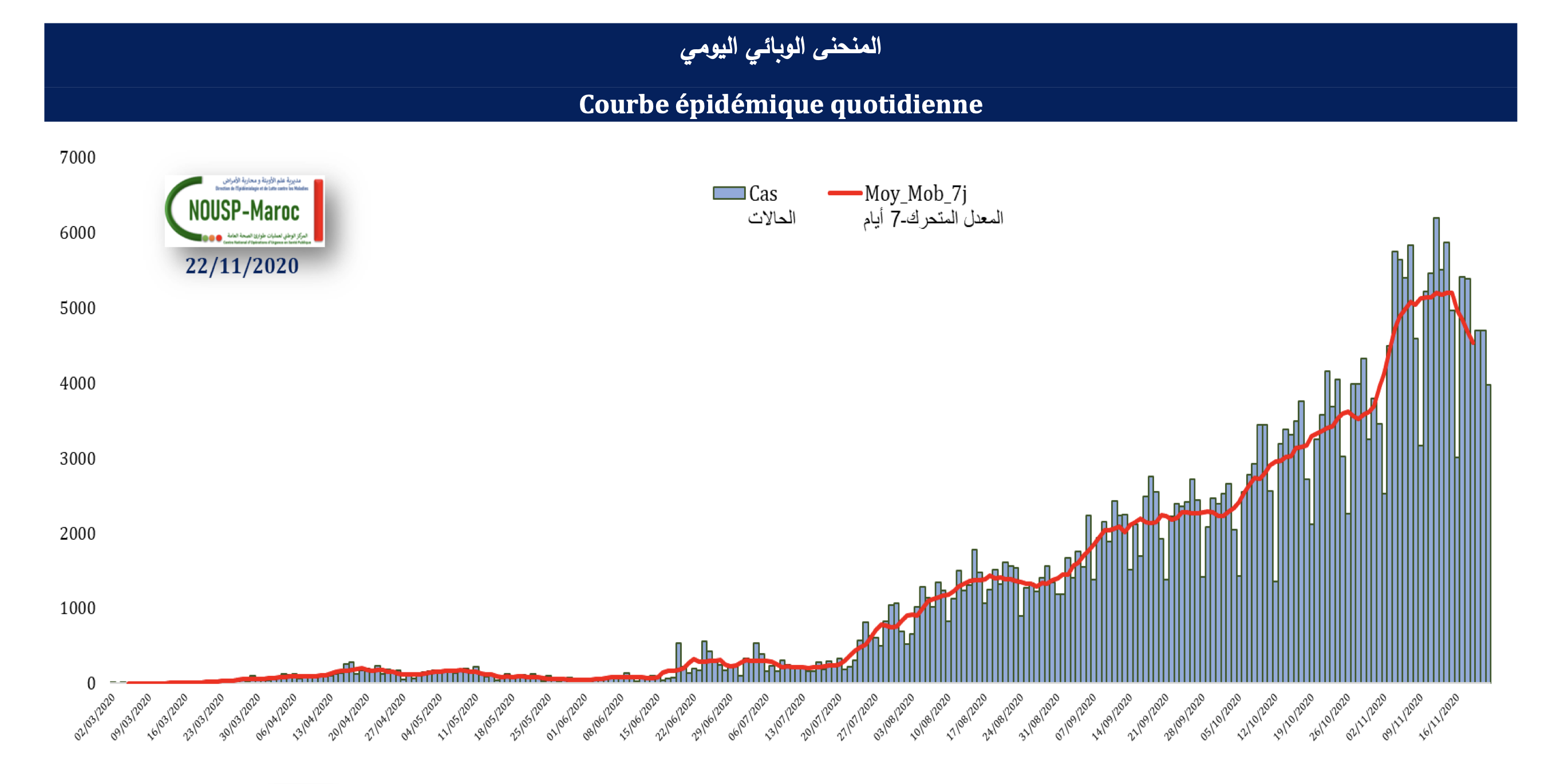

By mid-November, the total number of cases of Covid-19 in Morocco reached 293,177 confirmed cases, including 4,779 deaths. The largest number of infections was recorded in October with 95,431 confirmed cases, representing nearly half of the total number of cases recorded since the first one in the country dated March 2nd. This important number recorded within one month confirms the increase in the number of cases by more than 37% compared to September.

It appears that the number of cases that the Kingdom recorded since the beginning of September to mid-November is more than four and a half times (4.6 times) what was recorded in the previous period, which reflects the aggravation of the epidemiological situation in the country. Moreover, Morocco went from 65th global rank in the number of cases indicator in mid-June to 32nd up to mid-November[1], in addition to the grade point average that increased from 69 cases per 100,000 people at the end of July to 603.3 per 100,000 people at the end of October. Plus, the basic reproduction ratio (R0) moved from 1.38 at the end of July to 1.9 at the end of October, noting that it had settled in 0.7 at the beginning of June and was crucial in the decision of lifting the quarantine.

Amid these worrying indicators, there is a question that determines the future of health security for Moroccans, and which this paper attempts to answer: Will the aggravation of the epidemiological situation lead to the collapse of the Moroccan health system?

The epidemiological situation during and after quarantine

Although Morocco still maintains the lowest fatality rates in the world at 1.7%[2], and that the recorded cases remain mostly benign and without symptoms[3], which is confirmed by the high recovery rate above 80%[4], the comparison between the period of quarantine and the one after its lifting showcase an ongoing breakdown in the rest of the epidemiological situation indicators.

During the period between March 19 and June 15, which was marked by the quarantine and the state of health emergency[5], three indicators demonstrate that Morocco was able to achieve stability of the epidemiological situation[6]: the first is the decrease of the Real-time transmission index (Rt) below 1; the second is that the number of active cases did not exceed 3 per 100,000 people; and the third is that the proportion of serious and critical cases was stable at 0.2%. It has to be noted that the number of confirmed cases did not reach 9,000, the deaths did not exceed 212, and the critical cases remained below 60.

However, immediately after the gradual lifting of quarantine and the resumption of economic activity, the epidemiological situation started escalating, despite taking urgent measures intermittently to cordon off the 1192 active foci (professional and familial) until October 25th[7]. As a result, the number of cases magnified by 24.7, the deaths by 17.4, and the critical cases count exceeded 800 until the said date.

A graph showing the development of the number of cases (Source: Ministry of Health’s daily Covid-19 bulletin)

The table shows the number of cases, deaths, and critical cases during and after quarantine

| After quarantine | During quarantine | |

| 2019084 | 8838 | Number of confirmed cases |

| 3695 | 212 | Number of deaths |

| 814 | Not exceeding 60 | Number of critical cases |

A trio pushing Morocco towards disaster

Despite official assurances about controlling the epidemiological situation[8], there are three challenges indicating that the health system in Morocco is under a state of increasing pressure and has reached a critical stage that may lead to the collapse of the health system if the situation is not remedied in the short term.

First: Difficult access to laboratory tests

Although the number of tests conducted increased from the daily average of 93 during March to 20,000 since mid-July, and Morocco is at the forefront of North African countries in this indicator[9], this number no longer accommodates the increasing demand for tests, being the only mechanism approved to find out whether a person is infected or not[10]. Furthermore, citizens complain about the difficulty of making an appointment to get tested, which may take days, in addition to the delay in obtaining the results for more than 48 hours[11], and the invalidity of analyses of citizens in some cities after the expiration of the samples taken[12].

There is a causal relationship between the delay in accessing laboratory analyses and the number of critical cases, as the latter doubled four times within six weeks, moving from 202 cases in mid-September to 814 at the end of October 2020. Therefore, doctors see the need to amend the Covid-19 diagnostic protocol, by treating patients so that the laboratory tests are not the only way to confirm citizens’ infection[13], especially when the main symptoms appear on the potential case and the x-ray examination reveals damage to the lungs.

It should be noted that Morocco relies on diagnostic tests that reveal whether the person is currently infected with the virus and is able to transmit the virus to others. After expanding the network of Covid-19 testing laboratories, Morocco also started conducting tests that reveal whether a person has been infected with the virus in the past and has been cured of it. For the diagnostic test, the “polymerase chain reaction” (PCR) is used. It consists of getting a swab from the person’s upper respiratory tract, that is, the throat, nose and mouth, before analyzing the sample to determine whether it contains the genetic factor for Coronavirus. If the genetic factor (or the “genome”) of the virus is detected in the sample, this means that the person has the virus. Antibody test is the second type of tests used to detect the Covid-19. Also known as “ELISA” technology, it is an enzymatic immunoassay that shows whether or not a person has been infected with the virus in the past. Generally, when the body is infected with any virus, the immune system creates antibodies to fight it. This test is done by taking a blood sample.

However, this second type is not recommended, as it is not suitable for the initial diagnosis[14]; this is because its result comes back negative if the patient is in the early stages of the disease, and it is preferable to use it in the follow-up of epidemiological examination in some professions.

Second: Malfunctions in managing the epidemiological situation

There is another worrisome indicator related to the difficulty in managing the treatment of Covid-19 asymptomatic patients at home, which was issued by the Ministry of Health at the beginning of last August, after the challenge of keeping up with their health condition and receiving the required medicines for treatment due to the lack of human resources.

Another malfunction was the missing of data from patients treated in the private sector. In fact, some patients whose analyses were conducted in private laboratories, were found to be positive cases[15], but the laboratories did not share the data with the Ministry of Health. The latter noticed this belatedly and consequently closed several laboratories. Although the most important thing for those who refuse to enter this perplexing situation is to resort to voluntary quarantine in their homes, failure to record their data and inform the local authorities of their situation may tempt them to return to their normal life, especially if they do not show symptoms of the virus.

Third: the instability of human resources and the weakness of the intensive care system

There are two other factors that contribute to the complexity of the situation and limit Morocco’s ability to deal with the pandemic, namely: Instability human resources and the weakness of the intensive care system.

Since the spread of the epidemic in Morocco, the Ministry of Health has witnessed a lack of stability in positions of responsibility, due to the dismissals that included senior officials in the ministry, and the several central, regional and provincial directorates that are currently being run on an interim basis in addition to hospitals. The Minister of Health Khalid Aît Taleb issued 59 dismissals in less than 10 months[16], which mainly included directors of regional and provincial hospitals in which Covid-19 patients were housed, and regional and provincial directors responsible for implementing policies to control the pandemic. Moreover, key positions in the ministry are being run on an interim basis since months, and this concerns the General Secretariat, the General Inspectorate, the Human Resources, Equipment and Maintenance Directorates, the National School of Public Health, the National Center for Blood Transfusion and the Communication and Information Department. It appears that this situation will last for a longer time, after 14 vacant or occupied senior positions and 164 positions of responsibility opened on September 15 and 16 only.[17]

Second: The imbalance in the map of the deployment of intensive care beds and physicians, which is characterized by four regions holding the largest share at a time when the intensive care system is the main indicator of the resilience of the health system of any country. In Morocco, there are no accurate figures on the number of intensive care beds allocated to critical cases, as each time the Minister of Health announces a different number.[18] Official statistics dating back to December 2019[19] (that is, three months before the first case was recorded in Morocco) reveal that the number of these beds does not exceed 557 in public hospitals, of which four regions account for 76% of them. They are in the following order: Fez and Meknes (114 beds), Marrakesh and Safi (113), Rabat and Kenitra (108) and Casablanca (89).

The government promised at the beginning of the epidemic to raise this number by three times, but after more than 9 months, this promise was not fulfilled as only 127 intensive care beds were added during this period.[20]

However, the biggest challenge is the lack of human resources, which exacerbates the epidemiological situation and impedes the development of the intensive care system. Indeed, Morocco has only 439 doctors specializing in intensive care and anesthesia in the public sector, distributed in an unbalanced manner, where 66% of them are concentrated in four regions, namely : Casablanca and Settat (81 doctors), Marrakech and Safi (77 doctors), Fez and Meknes (73 doctors), Rabat, Sale and Kenitra (60 doctors). All these figures make Morocco far from the international standards in this area, which stipulate the provision of 20 intensive care and anesthesia doctors for every 100,000 people, so that the health system is able to guarantee intensive care services for its citizens. Morocco has only 1.22 intensive care and anesthesia doctors for every 100,000 people[21].

The weakness of the intensive care system will accelerate the collapse of the health system in the event that the number of serious or critical cases continues to rise. This number reached 1051 cases in mid-November, including 549 cases under invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation,[22] moving closer to filling up the intensive care beds with Covid-19 patients. Plus, intensive care beds in the public sector are supposed to receive all patients in critical condition, not just Covid-19 patients.

Conclusion

The epidemiological situation appears to continue to deteriorate on multiple levels, as it is reflected in the ever-rising number of cases and critical cases. While front-line doctors warn of the danger of the collapse of the national health system, this paper proposes solutions to develop a diagnostic, treatment, and patient tracking procedure that revolves around the triad of diagnosis, treatment, and governance.

For diagnostics, it is important to increase the capacity of RT-PCR tests and their regional distribution and to provide quick results. This will not be possible without opening new laboratories, enhancing their capabilities, and engaging the maximum number of private laboratories, while ensuring tests are at an appropriate price compared to the current high prices, as well as providing the regions containing a lot of cases with mobile laboratories. Furthermore, laboratory tests should be abandoned as the only mechanism for diagnosing the disease, because the number of cases that need to be analyzed daily is much greater than the capacity of hospitals.

With regard to treatment, primary care physicians in the public and private sectors must be granted the authority to prescribe medication under special conditions: a mandatory declaration of disease, a clear national protocol, the possibility of conducting tests in the two sectors, and insurance. It is also time to involve private clinics in the care of Covid-19 patients according to the applicable national protocol, and prescribe medication based on clinical symptoms. To apply this, a new and clear protocol must be developed, pursuant to the principle of rapid treatment, based on clinical assumptions before the results of the tests.

As for governance, a return to partial quarantine may be a solution to reduce infection rates, especially in provinces and prefectures that are experiencing deterioration in this regard. If a comprehensive quarantine is economically heavy and can cost more than one billion dirhams per day, then partial quarantine can be an effective way to control the pandemic until the start of the vaccination process in the coming weeks.

Footnotes

[1] According to the recent update of the global specialized website “channelnewsasia”: https://infographics.channelnewsasia.com/covid-19/map.html

[2] – The Covid-19 official page, the Ministry of Health website, at: http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Pages/LESINFOAR.aspx

[3] The presentation before the Council of Representatives’ Social Sectors Committee, Professor Khalid Aît Taleb, Minister of Health, September 17, 2020, page 19.

[4] The Covid-19 official page, the Ministry of Health website

[5] Decree-Law No. 2.20.292 issued on Rajab 28, 1441 (March 23, 2020) regarding the enactment of provisions for the health emergency and the procedures for announcing it, official bulletin, No. 6867 bis, dated Rajab 29, 1441 (March 24, 2020), page 1782.

[6] Presentation of the Minister of Health, page 7

[7] The Minister of Health admits: The epidemiological situation is very worrying … and we have recorded 1192 active foci, Kifach, October 26, 2020, at: https://kifache.com/%D9%88%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D8%AD%D8%A9-%D9%8A%D8%B9%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%81-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A-%D9%85%D9%82%D9%84%D9%82-%D8%AC%D8%AF/

[8] The last of which was the speech of the Minister of Health, Khalid Aît Taleb, in the House of Representatives on September 17, 2020, stating that the situation is alarming, but has neither not got out of hand, nor has it reached the level of pressuring the capabilities of the national health system or exhausting the extensive efforts of the healthcare teams.

[9] “Covid-19” … Morocco ranks second in Africa and first in North Africa in terms of the number of conducted analyses, MAP, July 25, 2020, at: http://www.mapexpress.ma/ar/actualite/%D9%83%D9%88%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%AF-19-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%BA%D8%B1%D8%A8-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%B2-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%A5%D9%81%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%82%D9%8A/%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B9-%D9%88%D8%AC%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AA/

[10] As stipulated in the treatment protocol of the Ministry of Health.

[11] The truth about what is happening inside the Ministry of Public Health, Al-Ayyam, Issue 911, September 10, 2020, page 11.

[12] Interview with Dr. Mohamed Zizi, citizens’ analyses expired and results were ready after their owners died, and more than a thousand analyses are awaiting in Rachidiya, Al-Ayyam, Issue 911, September 10, page 14

[13] Interview with Ahmed Ghassan Al-Adib, intensive care professor, Four Wheels Leading Us to the Epidemic Disaster, Al-Ayyam, Issue 911, September 10, page 12.

[14] ibid

[15] The truth about what is happening inside the Ministry of Public Health, Al-Ayyam, Issue 911, September 10, 2020, page 11.

[16] The Minister of Health “breaks the record” by dismissing 59 officials within a year, Hespress, September 18, 2020, at: https://www.hespress.com/societe/484435.html

[17] The Ministry of Health opens the door for applying for 14 high-ranking positions, le 360, September 21, 2020, at: https://ar.le360.ma/societe/169832

[18] Mohamed Karim Boukhassas, The Shocking Facts about the Collapse of the Health System in the Kingdom, Al–Ayyam, Issue 920, November 12, 2020, page 16.

[19] Obtained documents of the Ministry of Health

[20] Yasser ElMakhtoum, The Pandemic … Frightening Facts and Missing Readiness, Akhbar Al-Yawm, Issue 3311, October 10, page 12.

[21] ibid

[22] Covid-19 Daily Bulletin, November 15, 2020, the official page of the Coronavirus, the Ministry of Health website, at: http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Documents/BULLETIN/BQ_COVID.15.11.20.pdf[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]