[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

While the quota system increased women’s representation in the Moroccan parliament, the cultural and socio-economic structures limited their participation in decision-making processes.

Download article

Executive Summary

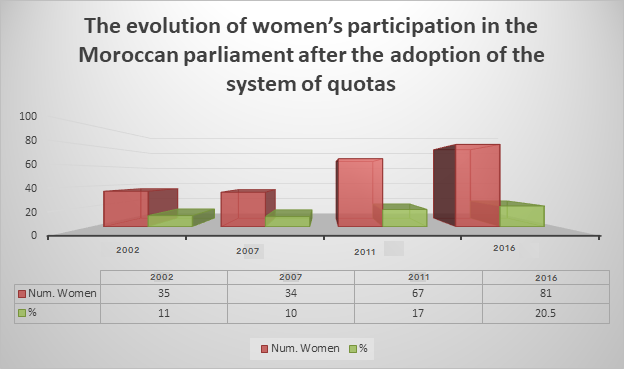

The quota system increased women’s representation in the Moroccan parliament significantly from two seats in 1993, to 81 seats in 2016 elections. Yet, despite the system’s success in increasing women’s representation in parliament, it failed in its main purpose of achieving broader participation for women outside of that system. Since the creation of that system in 2002, a limited number of women that succeeded to get elected outside the system of quota. The failure is a result of cultural and socio-economic structures that limit women’s participation in decision-making processes.

Introduction

Morocco first witnessed women run for office 1993, when two women won seats in the parliamentary elections that year. This achievement shed light on the issue of women as a “precarious” segment of society and raised questions about how their integration in the political process, including parliament, could improve their overall situation.

Based on this assumption, Morocco adopted the quota system in 2002 in order to guarantee a minimum level of representation for women in the legislative establishment. Morocco also implemented proportional representation through a closed party-list system, helping 35 women secure 11% of parliamentary seats that year. Thus, a consensus among the various parties has been achieved to allocate a list for women in the legislative elections. This agreement was done thanks to pressures from the government that aimed to integrate more women in the political sphere including the parliament. Under this consensus, each party presents a women’s list to the electorate to be voted on nationally throughout the electoral districts.[1]

At first glance, the adoption of the quota system aimed to facilitate women’s access to the political sphere. Yet, a deeper look to the results of four legislative elections (2002, 2007, 2011, 2016), demonstrates that this approach failed in its main objective, which is the promotion of a new generation of leaders capable of competing with men outside the quota system. This failure raised doubts about the system’s effectiveness in challenging male domination of the political sphere and whether this tool is capable of changing the stereotypes on women as “less capable” of holding decision-making positions.

The Quota System

As a mechanism of affirmative (or positive) discrimination, the quota system is used to facilitate the access for disadvantaged groups into representative structures. Governments around the globe use this tool to integrate groups that face racial, religious, or sexual discrimination, with women and youth quotas being the most widespread tool for positive action in politics. In fact, this system allowed for tangible results in terms of women’s representation in parliament, yet, some criticism of the system has been raised, describing the quota as undemocratic as it does not assure equal rights and opportunity between males and females.

Although there is some truth to this view, the quota system generally derives its legitimacy from the principle of justice, which requires the representation of a broad and disadvantaged segments of society, in this case, women. The quota system is also seen as the optimum interim solution for a society that still believes, to a certain extent, that women are inept for political and decision-making positions.

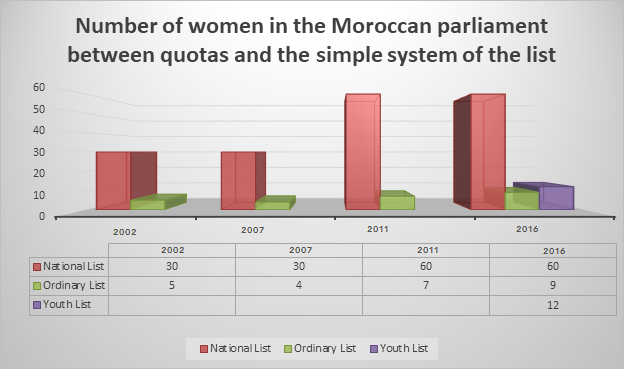

In Morocco’s 2002 elections, 30 out of 325 seats were allocated to women in the national list, guaranteeing parliamentary seats for 30 women, in addition to only five others who succeeded in winning seats under the same rules of competition as men (i.e. without the quota). In 2007, only four women managed to win seats outside the quota system, bringing the total number of women in parliament down to 34, or 10%.

In 2011, constitutional reforms included a new regulatory law that increased, through a legislative mechanism, the number of parliamentary seats allocated to women from 30 to 60. This enabled a total of 67 women to win seats in parliament that year, accounting for 17% of all seats. Parliament also ratified a law pertaining to the local elected councils, which increases women’s representation inside local councils (municipalities and rural councils) from 12% to 27%. As for the most recent legislative elections in 2016, women win 81 of 395 seats, or 20.5%; 60 seats through the national women’s list, 9 through regular (non-quota) lists and 12 through the youth list, which approximately 4% increase.[2]

Despite these apparent gains, however, women’s representation in parliament increased only marginally because after four electoral cycles (2002, 2007, 2011, and 2016) with the quota system in place the number of women outside of the quota system remained constant (between 4 and 9 seats), which raise the doubts of the effectiveness of the Quotas system as a tool to improve women inclusion in the political process.

Political Culture

To understand the limits of the quotas system to improve women political participation one should look at the dominant political culture, which seems an obstacle for more inclusion. the unwavering “masculine mentality” in Morocco is rooted in beliefs that in men’s political performance are higher than women. in addition, women face the spread of nepotism within their own political parties, reflecting negatively on the role that women play and raising questions about the quality and competence of female candidates put forward by the parties. All these factors reflect on women’s performance within the elected councils and hinders progress in overcoming existing stereotypes about women.

Furthermore, the political parties’ structures were not improved enough to meet with the constitutional reforms. This is clear at the level of the absence of equality in decision-making positions within the political parties. With the exception of the Unified Socialist Party (FGD), which is led by a woman, no party has offered a female member the post of secretary-general. Moreover, candidates for the political bureau and other higher positions inside the parties are typically limited to party leaders’ inner circles. And, although some political parties, such as the Justice and Development party (PJD) and the Istqlal party (PI), established committees dedicated to the question of equality, this has not significantly improved the status of women inside the parties.

In fact, the subject of the quota system has brought to light an important public debate regarding its usefulness and effectiveness in improving women’s status within the political sphere. Critics of the system consider it “political rent,” an argument that is contested by women’s rights activist Latifa El Bouhssini. The quota, she argues, represents “an international effort that came as a measure within the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against women.”[3] However, she adds, its application in non-democratic regimes transforms it into a political rent. Nonetheless, El Bouhssini affirms that this experience “is more positive than negative.”[4]

Supporters of the quota system, meanwhile, view it as part of a framework for positive action towards women. MP Ibtissam Azzaoui, a member of the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM), argues that the quota allowed women MPs to shed the light on social issues and laws that “would have gone unnoticed,” referring in this context to article 19 of the 2011 constitution, which establishes an authority for parity and the fight against all forms of discrimination. MP Azzaoui expressed that “the extensive debate that accompanied the law and the scale that it took regardless of the text, would not have been possible without female MPs.”[5]

Some studies point to the persistence of traditional conceptions about the role of women in the political sphere, which consider women incapable of engaging in political action and unable to make decisive decisions. These conceptions also consider women less capable than men, who are seen to be more rational and responsible. To that effect, Mokhtar El Harras concludes in his book Women and the Political Decision, that the patriarchal norms embodied in relations of dominance and submission still play a major role in perpetuating gender inequality.[6]

Yet, an EU report[7] found that all countries around the world have made significant gains related to women’s political participation, despite the slow pace of that process, owing to the time lag between the granting of rights and their exercise. This lag is further exacerbated by the delay in attaining decision-making positions in the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary, as well as in the private sector and the job market.

Women’s integration in political life is not only dependent on their participation in parliament and the elected councils, however. It is also directly related to women’s empowerment to take vital decisions within the state and encouragement to participate politically in various fields. This, in turn, clashes with the structural imbalance between men and women, which effectively impedes women’s broad participation in public affairs.

A Structural imbalance between men and women

The low level of female participation outside the quota system reflects not only a weak culture of involvement within political parties, but also illustrates the structural imbalance between men and women on the economic level. For instance, women suffer from higher illiteracy rates than men, especially in rural areas. According to the 2014 general census, almost 42% of Moroccan women are illiterate, compared with 22% of men.[8],[9] This discrepancy is due in large part to the declining standard of education and the increase in school dropouts in Morocco, which prevents girls in particular from continuing their education.

Additionally, women still suffer from higher rates of poverty and unemployment than men. According to the High Commissioner for Planning (HCP), the unemployment rate among women stands at 14.7%, compared with 9.8% for men.[10] And, although the government and civil society organizations have taken some remedial steps on this front, namely implementing small projects in villages in poor areas and promoting local production and microenterprise, these measures appear to be insufficient, especially in light of Morocco’s current economic conditions and crises.

Conclusion

Although the quota experiment is important to women’s participation in the public sphere, it has yet to yield the desired results, indicating that legislation alone is insufficient in empowering women and providing them access to decision-making positions. To do so would require not only the legislation of new public policies that would allow women to participate, but would also require policies to reduce the structural imbalance between men and women on the socioeconomic level. Unless the structural imbalance is addressed and there is a change in the “masculine mentality,” the quota system will fail to achieve its primary purpose of broader participation for women in the political sphere.

Notes

[1] Driss Lagrini “The quotas and its role in the empowerment of women,” Journal massalik al fikr fi syassa wa iqtissad , 23-24 / 2013. p. 55. (in Arabic).

[2] Address by Mr. Rachid Abadi, Deputy Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies at the opening of the Regional Seminar on Women in Politics, website of the House of Representatives, July 2018, link: http://www.chambredesrepresentants.ma/ar

[3] See: “Women’s Quotas … Means to Raise Women’s Political Participation or Political Revenue?”, August 2016, http://lakome2.com/politique/17753.html

[4]Latifa Bouhssini, Moroccan human rights activist and feminist, website asswat Magharebia, for more information please visit:

https://www.maghrebvoices.com/a/Moroccan-women-parliament/389216.html

[5]Halima Abruk: Women in parliament … What did they offer to Moroccans? Published on asswat Magharebia website, for more information, please visit the following link: https://www.maghrebvoices.com/z/622/2017/9/5

[6] Mokhtar Al-Harras: Women and Decision-Making in Morocco “The University Foundation for Studies and Publishing, First Edition 2008.

[7] Report on the analysis of the regional situation, “Women’s human rights and gender equality in the Euro-Mediterranean region”, Promoting equality between men and women in the region. Funded program issued by the European Union.

[8] The rural/urban discrepancy is even greater with almost 48% illiteracy among rural populations, compared with 22% in urban populations.

[9] Newsletter of the High Commissioner for Planning, on the occasion of World Literacy Day, website of the High Commissioner for Planning, 2017, link https://www.hcp.ma/Note-d-information-du-Haut-Commissariat-au-Plan-al- occasion-de-la-journee-internationale-de-l-alphabetisation-du-8 a2009.html

[10] the situation of the labor market during 2017, website of the High Commissioner for Planning, March 2018, link https://www.hcp.ma/La-Situation-du-marche-du-travail-en-2017 a2108.html

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Ikram Adnani

Ikram Adnani is a professor of political science and constitutional law at Ibn Zohr University in Agadir, Morocco. She is an active member in many think tanks. Her main academic research concerns are on women, youth, migration and minorities. She has published many articles in Moroccan and Arab journals.