Morocco’s migration policy reflects of the interconnectedness of foreign policy priorities, desired reform and the reality of domestic politics. Morocco has positioned itself as a counterterrorism and migration ally for Europe; while leaning toward the African Union, and African markets.

Download article

Abstract

Morocco hosted the Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, known also as the Global Compact for Migration (GCM), in Marrakech in mid-December 2018 under the sponsorship of the U.N. General Assembly. (1) GCM was perceived by the international organization as “a milestone in the history of the global dialogue and international cooperation on migration,” and was “rooted in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, and informed by the 2013 Declaration of the High-level Dialogue on International Migration and Development.”(2)

The new pact asserted that refugees and migrants are “entitled to the same universal human rights and fundamental freedoms, which must be respected, protected and fulfilled at all times. However, migrants and refugees are distinct groups governed by separate legal frameworks. Only refugees are entitled to the specific international protection defined by international refugee law.”(3) The adoption of such a paradigm was in concert with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations; and proposed “a 360-degree vision of international migration”, and calls for the need for “optimizing the overall benefits of migration, while addressing risks and challenges for individuals and communities in countries of origin, transit and destination.”(4)

The Global Compact for Migration, a non-binding agreement signed by 164 countries, showcases a “cooperative framework that builds on the commitments agreed upon by Member States in the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants”, while acknowledging, “No State can address migration alone, and upholds the sovereignty of States and their obligations under international law.”(5) However, the meeting and the subsequent pact signed in Marrakech triggered some controversy, since some countries such as the United States, Australia, and Hungary, refused to attend or sign the new agreement. Other countries including Italy, Bulgaria, Israel, and Switzerland remained undecided about the new accord.(6) The contextualization of this array of positions ushers to an unsettled debate about the cost and benefit, security risks, and humanitarian imperatives towards “over 258 million migrants around the world living outside their country of birth.”(7)

Despite these contentious reactions to the trajectory of the new pact, there is still consensus around the need for better management of the migration flows; and that the refugee crisis needs to be addressed sooner than later. The location of the meeting in Marrakech indicated the significance of Morocco’s role in managing and supporting a new path toward migration reform. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has categorized Morocco as a country that “has increasingly become a place of destination for refugees and migrants.” Refugees in Morocco originate from 38 countries, and 59 per cent of them came from Syria. The total number is poised to increase in 2019 to 8700 people residing in 50 locations across the country.

In this paper, Anna Jacobs proposes an assessment of the 2014 new migration policy that Morocco, the host nation of GCM, has adopted vis-à-vis the influx of migrants and refugees from sub-Sahara Africa, Syria, and other parts of the Middle East. She probes into what seems to be a dichotomy between the normative value of Morocco’s policy and the struggling implementation, or the reported “repressive measures” taken by the government against African migrants, at various incidents since 2014. She studies some “incoherence” and “contradictions” in pushing the country’s migration policy forward, and explains how the government’s approach to the implementation of the new policy has undermined the potential positive aspects of the legislative and political reform. To develop a nuanced interpretation of how Morocco’s migration policy has been shaped in the last four years requires analysis of the interconnectedness between domestic, continental and Mediterranean factors, as well as evoking several perspectives of various stakeholders, mainly the European Union, sub-Sahara countries, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), non-governmental organizations, and the impact of local civil society groups.

Introduction

Located at the tip of North Africa 17 kilometers away from the southern cost of Spain, Morocco is at the heart of migration flows between Africa, Asia, and Europe. It has also accumulated three reputations associated with migration: ‘a country of source’, ‘transit’, and ‘destination’. Local border control officials in Tangiers have pointed out, “Traffic on the central route from Libya to Italy has gone down by 150 percent, which means that we are facing networks who are adapting their strategies to the reaction of different European countries. But in dealing with this, Morocco is applying its law.”(8) However, international human rights advocacy groups have condemned what they have termed “large-scale crackdown” as “cruel and unlawful”.(9) Amnesty International has pointed out that at least 5000 people have been “swept up in the raids” around Morocco, “piled on to buses and abandoned in remote areas close to the Algerian border or in the south.”(10)

During delivering his speech at the Marrakech UN meeting, Morocco’s foreign minister Nasser Bourita emphasized his country “is fighting smuggling and human trafficking networks that are using the territory to endanger the lives of these migrants. We’ve dismantled the trafficking cells and worked to save the lives of a large number of migrants.”(11) He also reminded his world audience of his government’s decision to grant 50000 residency permits to migrants, while easing access to the job market, health and education. Bourita referred to Marrakech as “the capital of migration”. So far, Morocco is the only country in MENA that has sought to enact significant migration and asylum reform.

After more than a decade of advocacy efforts by the Moroccan civil society, King Mohammed VI officially announced a plan to enact a “humanitarian approach” to the country’s migration and asylum system in late 2013.(12) This step led to the creation of a governmental department to oversee migration affairs, the distribution of the first round of refugee and asylum seeker cards, and and the adoption of the 2014 ‘National Strategy on Immigration and Asylum by the Council of Government’. The new policy included a status regularization program for undocumented individuals living in Morocco. It has also improved access to residency cards for undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. The international community recognized Morocco’s efforts to reform the immigration and asylum system, and leading the way in migration reform in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.(13)

At the international level, Morocco and the United States were the only two non-European countries to attend the G6 Interior Ministers meetings held in October 2018, including major EU countries: France, Germany, United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and Poland. These talks focused primarily on security cooperation, counterterrorism efforts, and better regulating irregular migration.(14) These issues represent key priorities for the European Union and the United States. Morocco’s presence at the meeting also reflected its strategic importance in shaping a migration and security strategy in the MENA, as well as the Mediterranean region.

Still, the prospects of positive change have not been in full swing while several legal obstacles and issues regarding access to resource are still unsettled. Morocco’s new policy was expected to pass a new legislation to reform the migration and asylum policy, and help mitigate the dilemma of human trafficking across the Mediterranean. Despite the limited implementation of such a policy, Morocco remains the only exception in the MENA region with a national system of asylum. In 2017, the number of asylum seekers jumped to 6779, a percentage of 87 of refugee and asylum-seeker children were enrolled in local primary schools, and 420 students received university scholarships in the country, according to the statistics of UNHCR.(15)

Still, several field reports have pointed to the continuation of harsh treatment of migrants continues by Moroccan authorities. A crackdown against sub-Saharan migrants, including police raids and human rights abuses, began in the summer of 2018. The Moroccan government neither denied these reports, nor contested the allegations that those raids took place in coordination with Spain and other EU members. Rabat justified those harsh measures by the need for “targeting” human trafficking and irregular migrants.

However, local human rights advocacy groups, such as Groupe antiracist d’Accompagnement et de Defense des Etrangers et Migrants (GADEM) and Association Marocaine Des Droits Humains (AMDH), have argue that the arrests included arbitrary arrest and detention, expulsion, and even detention of minors. According to GADEM, Moroccan authorities have detained and displaced 6500 migrants since June 2018.(16) At a camp the port city of Casablanca, one migrant from Ivory Coast recalls his experience with authorities: “I was arrested and put in a police car with dogs. From the police station, I was put on a bus with other migrants and taken near the Algerian border. I, then, had to beg on the streets to make enough money for a bus ride back up.”(17) These revelations seem to contradict the “humanitarian approach” espoused by the new 2014 migration policy, and raise new questions about the real intent of the King’s promise within the temporal and political context.

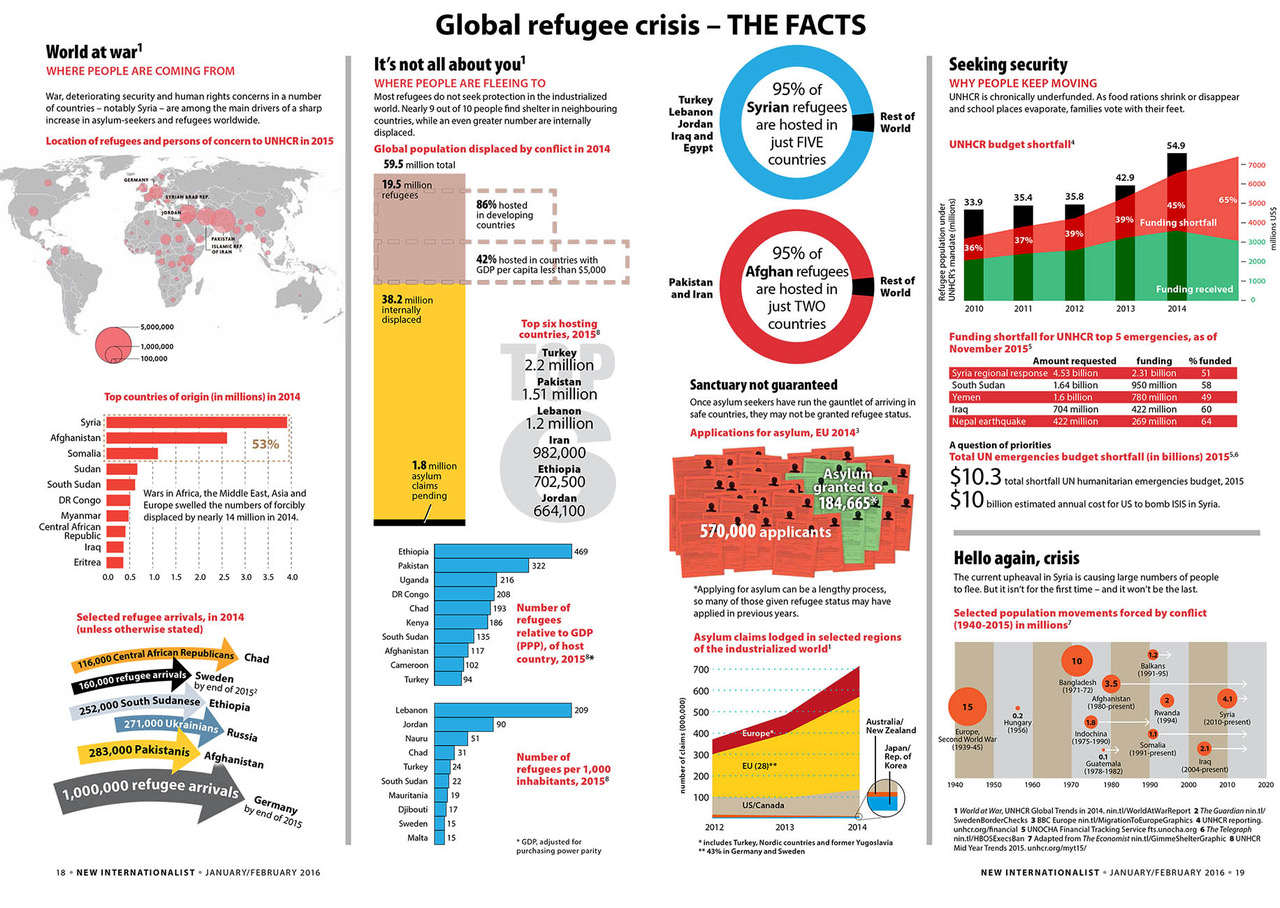

Global Refugee Crisis (New Internationalist)

Political Reform within Morocco

Debates about the nature of political reform have taken center stage in Mohammed VI’s Morocco in the last two years. The more optimistic group, which tends to dominate the public sphere, highlights ‘greater freedom’ of expression, presence of key democratic institutions, and a vibrant civil society. They also point to what they consider improvement in Morocco’s record of human rights, including women’s rights, since the King ascended to the throne in July 1999, and the rupture with past abuses in the era of his father Hassan II, known as ‘Les Années de Plomb’ (Years of Lead), mainly between 1960s and 1980s. This shift has entailed various reform projects during the reign of Mohammed VI, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the family code reform, promises of media liberalization,(18) and other political concessions offered in the aftermath of the 2011 protests.

The King’s reform initiatives tend to affirm a rather unilateral and informal process in Morocco. These political openings have not been supported by institutional changes, but rather demonstrate occasional ad hoc reform impulses. Some critics argue that these changes may have some positive effects in the short term; but, do too little to challenge the monarchy-based authoritarian system, which remains at the center of political life today. The political and economic influence exercised by the Royal Palace and the financial elite is considered one of the main limitations to political liberalization.(19) One Moroccan activist expressed concern that he had much less freedom in 2018 than he had had in 2011; “We are not living under the rule of law. Our constitution is not democratic, despite a few improvements in the wording. The Makhzen [central power] is clever. Nothing is ever formalized and hence any progress is reversible.”(20)

According to the 2018 Transformation Index (BTI), prepared by the Germen Bertelsmann Stiftung, “Morocco is a liberalized autocracy, so there is no consensus on democracy. All the political parties fall within the autocratic orbit of the monarchy… Democratic institutions are weaker than they could be from a constitutional point of view as the national government and municipal councils include a multitude of parties preoccupied with infighting over ministerial and other political posts and resources.”(21) In short, the 2011 dynamics and the emerging disarticulation between state and society have been significant in introducing other aspects of reform. The local civil society has been robust in seeking real change including the legal and socio-cultural approach to migration.

2014 Breakthrough

In recent years, several Moroccan civil society groups, like GADEM and AMDH, as well as a host of migrant-led organizations, have been resilient in pushing their advocacy agenda forward. There was also negative international media coverage of Morocco’s treatment of sub-Saharan migrants, as well a series of disturbing reports prepared by GADEM, Medecins sans Frontieres (MSF-Spain), and the National Council of Human Rights (CNDH) documenting widespread human rights abuses. CNDH, a palace-funded body, offered a host of proposal drafts with promises of new migration and asylum laws that would ensure better protection for migrants, a comprehensive strategy to battle human trafficking, and a regularization program that would help irregular migrants obtain residency permits. Both UNHCR and IOM have worked for years in Morocco. However like with other reform processes in the Kingdom, the palace, political elites, and subordinate institutions take center stage in policymaking and move at their own pace

CNDH has collaborated with various local civil society groups in supporting a new policy, and there was an apparent momentum for change. King Mohammed introduced a new migration policy in September 2013, and paved the way for the legislative adoption of a new law known as Law 02-03. Since then, the parliament in Rabat has not passed any laws to amend or replace the existing law, which governs migration related issues in Morocco.

Morocco’s 2013 migration policy could be a good point of entry in regulating a complex field of social work and economic empowerment. However, there is still need for domestic legal frameworks to help ensure proper implementation of a more humane migration policy that would respect the standards of international law in terms of asylum, refugee status, the principle of non-refoulement, (or forced deportation) and providing human rights protections for persons regardless of their legal status. This kind of objectives kept the activist mood focused on highlighting other grievances. They also paved the way for two important achievements in 2014 and 2017, which helped nearly 50000 irregular migrants gain access to residency permits.(22)

Since 2014, the implementation of Morocco’s migration policy has had several up and down turbulences. Civil society organizations like GADEM and AMDH have maintained their fieldwork, and lobbied for real and sustained reform. Meanwhile, the wave of optimism triggered by the King’s speech in September 2013 stared to fade away. While the political discourse emphasized the ‘virtues’ of implementing the first Regularization Program in the country, raids against sub-Saharan migrants have continued in the last four years.

Renewed abuses were cited in the “Expulsions Gratuites” report published by GADEM and in the New York Times in October 2018. The incidents included the arrest and displacement of about 6500 migrants; “The government has also begun expelling some migrants, rights groups say. 91 migrants including six minors have been expelled since the beginning of September. Another 37 remain in arbitrary detention.” (23) These draconian measures seem to indicate Morocco is back-peddling from the promises of reform made by the Monarch. They also raise new concerns about their trajectory.

An annual festival known as “Migrant Scene”, organized by GADEM was set to take place in Tangier in December 2018 was canceled. The organizers have sought to raise awareness about migrants and cultivate solidarity, tolerance, and understanding. The Moroccan authorities decided to ban the event without giving any explanation or justification. Mehdi Alioua, founding-member of GADEM and professor of Sociology at the International University of Rabat, wrote on his Facebook page, “The Moroccan authorities say they have changed their migration policies. The change did become a reality with the two regularization campaigns and a minor change in the treatment of foreigners from the ministry of interior. But besides that and some other small actions, there was no implementation of this change… Worse still, the poor treatment of sub-Saharan migrant started again; it’s on the rise after major outbreak this summer.”(24)

“Migrant Scene” Festival (GADEM)

Morocco’s 2014 migration policy has entailed several problems; one of them is lack of implementation. The public praise of this policy, two regularization programs, and the whole rhetoric about the new approach toward migrants and refugees have not led to full-fledged new legislations. The policy remains rather procedural, and desperately needs a legal framework to give it teeth. The migrant and refugee community still struggles with access to essential services including education for children, access to health care, and the ability to obtain a work permit. The administration of the Refugee Status Determination process officially remains with the UNHCR, not under the jurisdiction of a Moroccan ministry—which implies more challenges in ensuring that UNHCR would recognize refugees and asylum seekers can obtain Moroccan residency permits. This reality reflects continued discrepancy between Morocco’s national legislation and its formal commitments to the international legal frameworks vis-à-vis the United Nations agencies and the European Union.

Recent reports have also indicated members of the sub-Saharan migrant community face persecution, even when they carry residency permits. A revealing article “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants”, published in the New York Times in October 2018, has depicted how Morocco has essentially enacted a policy of systematic racial profiling and arbitrary arrest. Sub-Saharan migrants, including some with legal residency permits, have been picked up and dropped off in southern cities in Morocco. The article also describes how police dress in civilian clothing and go into the home of migrants, load them up, and take them to remote locations in the country or near border areas. This level of repression again the migrant community has also led to rising racism and xenophobia throughout the country.(25)

It is important to note these practices have occurred in Morocco while the rise of right-wing and populist movements in Europe and the United States has pushed for anti-immigration and anti-tolerance debate in the public square. Paradoxically, some Moroccan officials may find adequate resonance and justification of their misdeeds toward the migrant and refugee community at home. Either at the national or international level, this anti-immigration sentiment entails a recipe of violence, intolerance, xenophobia and racism, and instability in the long term—especially for countries like Morocco. But, Morocco and neighboring countries are not well-positioned to manage the migration complexities alone.

Diversity of Migration (Getty)

EU-Morocco Relations

Historically, Morocco has long been a source of migration since the 1970s, as waves of labor seekers crossed to Europe. Since the 1990s, it has become a country of transit and destination for migrants coming from sub-Saharan Africa. Exact numbers vary, but most organizations posit that around 70000 sub-Saharan migrants currently reside in Morocco.(26) North African countries, especially Morocco, have been labeled Europe’s “policeman” for supporting the EU’s “externalization of the migration problematic.”(27) Morocco has often pushed back, at least rhetorically, against this role.(28) From a strategic angle, it has used the migration question as a valuable bargaining chip in managing its relations with the EU, as well as in bilateral relations with countries like Spain.

The security-border control strategy is a slippery slope. The alleged human rights abuses against migrants, especially women and children, have resulted into more funding from the European Union for various initiatives in Morocco with the aim of providing assistance to the most vulnerable.(29) One recent funding initiative was a $275 million package “to help with basic services and support job creation” with the objective of curbing “illegal migration.”(30) This philosophy of aid packages and humanitarian initiatives is often overshadowed, not to say undermined, by internal politics and the often-cited paradigm “securing the border”, and other narratives of keeping migrants away from the European Union countries.

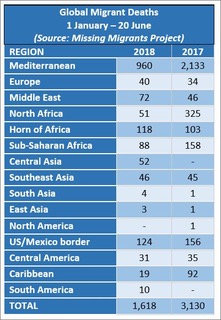

Global Migrants Deaths (Missing Migrants Project)

In late 2018, Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, proposed creating a border security unit of 10,000 men. Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, and Sebastien Kurz, Austrian chancellor, have also announced plans for further migration cooperation with Egypt, in spite of the rise in human rights violations and authoritarianism there.(31) They have plans to organize an EU-Arab League summit in Cairo next year, and formulate better migration control mechanism, a strategic issue that may take precedence over human rights concerns in MENA region.

Regional disembarkation proposals were presented earlier in 2018, even though these were strongly criticized by every state in North Africa.(32) A key condition in these proposals is that third countries must be determined “safe” and “respect non-refoulement.” However, countries like Morocco,(33) Algeria,(34) Libya(35), and Egypt,(36) do not often respect the principle of non-refoulement, nor are they particularly safe for migrants from sub-Saharan Africa. All these countries have engaged in practices of raids, arbitrary arrests and detention, and deportation of vulnerable persons, including asylum seekers, refugees, pregnant women, and minors.

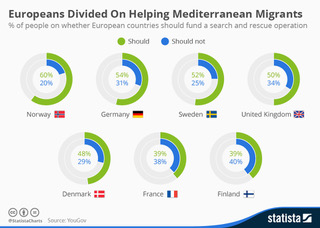

Europeans divided on helping Mediterranean migrants (Statista)

Morocco: Out of Africa, Onto Africa

Another key factor in determining the potential of Morocco’s migration policy is the perception and ties with Africa. The 2014 migration reform process, especially the regularization programs, aimed at highlighting some openness toward migration coming from the south. This perspective has aligned with Morocco’s foreign policy and economic plans to shift attention toward the continent—a move rooted in the strategy of rejoining the African Union (AU) and expanding into African markets. However, one potential cause for Morocco’s controversial migration policy derives from the foreign policy orientation. Morocco’s openness towards Sub-Sahara Africa, in terms of markets and movement of people, is often limited by the EU’s pressure to secure its northern borders and keep migrants and refugees far from Europe’s shores.

Furthermore, Morocco’s diplomatic overtures to the African Union were embedded in its efforts to seek an international legitimacy for its disputed ‘sovereignty’ over Western Sahara. Morocco’s re-entry into the AU, in January 2017, was conceived as a diplomatic victory that would offer hope for peacebuilding.(37) Morocco maintains a de-facto control over the majority of the territory, and remains attached to fulfilling the promise of the 1975 Green March: the validation of international bodies such as the AU and the U.N of the Moroccan territorial control. After a diplomatic stalemate over six years, UN-brokered peace talks resumed between Morocco, Algeria, the Polisario, and Mauritania in November 2018.(38)

King Mohammed spent much of 2016 traveling around Africa to secure support for his bid to rejoin the African Union, offering sizable foreign investment and business deals in several capitals. These trips resulted in more than fifty bilateral agreements with African countries and spearheaded talks of Morocco joining the ECOWAS bloc. According to the OCP Policy Center, Morocco is currently the second largest African investor in the continent, after South Africa.(39)

Morocco’s strategy of expanding into the African market seems on the path of success, even though important questions remain about their potential membership in ECOWAS. Moroccan exports in Africa increased by around 9 percent every year from 2008 to 2016. Significant foreign direct investment flows have grown by 4.4 percent, and countries like Nigeria, Senegal, Mauritania, and the Ivory Coast have become the principal buyers of Moroccan products on the continent.(40) As economist Riccardo Fabiani writes, “Most importantly, Morocco’s long-term goal is to become a trade and production hub that can interface between European, American, and Sub-Saharan African trading blocs.”(41)

Sub-Saharan migration represented a crucial dimension in Morocco’s shift toward Africa in 2010s. As mentioned earlier, the regularization program gave residency permits to a majority of undocumented migrants and refugees in 2014, a limited appeals process occurred in 2015, and another regularization process took place in 2017. According to the World Bank, more than 25000 individuals received one-year residency permits from 116 different countries included in the 2014 regularization process. All women and children who applied were accepted, and the overall acceptance rate was over sixty-five percent. The migrant population came mostly from Senegal (twenty-five percent), Syria (twenty percent), and Nigeria (nine percent).(42) The second round of regularization was announced in 2017, around the time that Morocco started making overtures to join the ECOWAS economic bloc. The second campaign legalized around 28,000 individuals.(43)

Overall, the regularization program has led to new conversations about Morocco’s reintegration into the African Union, economic cooperation, and free movement of people between Morocco and Western African countries. Yet, the prospects of this shift, which started in 2014, has been overshadowed by continued police raids of sub-Saharan migrants, as well as poor living conditions experienced by many migrants and refugees throughout the country.(44)

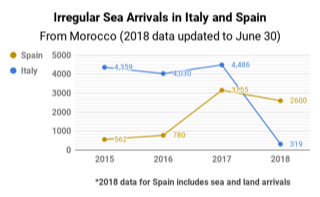

Irregular Sea Arrivals in Italy and Spain (Getty)

Conclusion: At a Challenging Intersection..!

Morocco’s migration policy is a reflection of the interconnectedness of foreign policy priorities, desired political reform and the reality of domestic politics. Morocco has positioned itself as ‘de facto ally’ for Europe in counterterrorism and migration control; while aiming at the African Union, ECOWAS, and African markets. This move toward Africa accentuates its significance in Morocco’s diplomatic modalities vis-à-vis the dispute over Western Sahara. This political tendency has shored up an added value for King Mohamed and the Moroccan private sector: the gains of financial and economic expansion into African markets.

Domestically, any process of political reform remains short-term, centralized, and often co-opted. Its primary aims are to mitigate criticism temporarily rather than substantively change policy in the long term. As described above, lack of, or improper, implementation of the 2014 migration policy continues to hinder the idea of reform. The no-follow up legislations for four years have left the migrant and refugee community economically, socially, and legally still very vulnerable.

Europe and Africa have a moral and political responsibility to step up their efforts and act as genuine partners in improving the Euro-Mediterranean migration system. It should include the formulation of long-term strategies that would focus on the root causes of the problem as well, rather than short-term or reactionary attempts to keep these human beings away from the Mediterranean. Europe must incorporate substantive avenues for regular, or “legal” immigration, to stymie the often-irregular mechanisms, or “illegal,” avenues that many people feel they must take.

Morocco seems to on the right track with its regularization programs, but needs a pragmatic mechanism of introducing, and overseeing the implementation of, a comprehensive socio-economic and legal migration policy.

This paper was jointly published with Al Jazeera Center for Studies.

References

- N., “Intergovernmental Conference 2018,” https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/intergovernmental-conference-2018,2018

- UNGA, “Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, Marrakech Dec. 11 and 11, 2018 A/CONF.231/3 http://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.231/3

- UNGA, “Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, Marrakech Dec. 11 and 11, 2018 A/CONF.231/3 http://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.231/3

- UNGA, “Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, Marrakech Dec. 11 and 11, 2018 A/CONF.231/3 http://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.231/3

- UNGA, “Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, Marrakech Dec. 11 and 11, 2018 A/CONF.231/3 http://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.231/3

- Faras Ghani, “UN members adopt global migration pact,” December 10, 2018, aljazeera.com/amp/news/2018/12/members-adopt-global-migration-pact-181210092353957.html.

- United Nations, Global Compact for Migration, December 2018 https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/migration-compact

- Faras Ghani, “Morocco’s migrants treatment under spotlight after UN conference”, Aljazeera,12 Dec 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/spotlight-morocco-defends-treatment-migrants-181212033244311.html

- Faras Ghani, “Morocco’s migrants treatment under spotlight after UN conference”, Aljazeera,12 Dec 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/spotlight-morocco-defends-treatment-migrants-181212033244311.html

- Faras Ghani, “Morocco’s migrants treatment under spotlight after UN conference”, Aljazeera,12 Dec 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/spotlight-morocco-defends-treatment-migrants-181212033244311.html

- Faras Ghani, “Morocco’s migrants treatment under spotlight after UN conference”, Aljazeera,12 Dec 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/spotlight-morocco-defends-treatment-migrants-181212033244311.html

- Royaume du Maroc, Ministère Charge des Marocains Résidant a l’Etranger et des Affaires de la Migration, “Stratégie Nationale d’Immigration et d’Asile,” http://www.marocainsdumonde.gov.ma/sites/default/files/Fichiers/Pages/strat%C3%A9gie%20Nationale.pdf, accessed December 1, 2018.

- “Immigration and Asylum Policy: Morocco Sets Example, UNHCR,” ma, October 3, 2018, http://www.maroc.ma/en/news/immigration-and-asylum-policy-morocco-sets-example-unhcr-0.

- “Morocco Takes Part in EU G6 Interior Ministers’ Meeting on Terrorism, Migration,” The North Africa Post, October 9, 2018, http://northafricapost.com/25747-morocco-takes-part-in-eu-g6-interior-ministers-meeting-on-terrorism-migration.html

- UNHCR, Global Focus: Morocco http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/10331

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants,” New York Times, October 22, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html.

- Faras Ghani, “Morocco’s migrants treatment under spotlight after UN conference”, Aljazeera,12 Dec 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/spotlight-morocco-defends-treatment-migrants-181212033244311.html

- See my Mphil Thesis, “Print Media and Political Reform in Morocco: the case of Le Journal (1997-2010)” Anna Jacobs

- Maghraoui “Introduction: Interpreting Reform in Morocco,” 143.

- lhem Rachidi, “So long to freedom of expression in Morocco”, the New Arab, June 27, 2018 https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/comment/2018/6/27/so-long-to-freedom-of-expression-in-morocco

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Morocco-Country report, 2018 https://atlas.bti-project.org/share.php?1*2018*CV:CTC:SELMAR*CAT*MAR*REG:TAB

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants, The New York Times, October 22, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants, The New York Times, October 22, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html

- Facebook post, Mehdi Alioua, co-founder of GADEM, November 10, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/mehdi.alioua.12/posts/10156951701390536

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants, The New York Times, October 22, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html

- Ibid.

- Stylianos Kostas, “Morocco’s Triple Role in the Euro-African Migration System,” Middle East Institute April 18, 2017, https://www.mei.edu/publications/moroccos-triple-role-euro-african-migration-system.

- Charlotte Bozonnet, “Maroc: ‘La seule politique migratoire coherente de l’Europe, c’est mettre de la pression sur les pays de transit,’”Le Monde, November 2, 2018, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2018/11/02/maroc-la-seule-politique-migratoire-coherente-de-l-europe-c-est-mettre-la-pression-sur-les-pays-de-transit_5377982_3212.html.

- S’exprimant à cette occasion, l’ambassadeur, chef de la délégation de l’UE à Rabat, Eneko Landaburu, a souligné que le soutien aux droits de l’Homme est un axe majeur et prioritaire dans la coopération entre l’UE et le Maroc : Dans la migration de l’Afrique subsaharienne vers le Maroc, il y a parmi les migrants de plus en plus de femmes et de plus en plus d’enfants, dont beaucoup sont non-accompagnés de leurs parents», a-t-il relevé, saluant à cet égard l’action de «Terres des Hommes», Gadem et l’association OEB, qui offrent un accueil humain aux femmes et enfants migrants au Maroc dans leur centre «Tamkine». Darcissac, Marion « Maroc: Terre des hommes renforce les droits des femmes et enfants migrants, » Terre des Hommes, http://www.tdh.ch/fr/news/maroc-terre-des-hommes-renforce-les-droits-des-femmes-et-enfants-migrants (April 1, 2012).

- Souhail Karam, “Morocco Gets $275 Million Aid from EU as Illegal Migration Rises,” Bloomberg, September 16, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-16/morocco-gets-275-million-aid-from-eu-as-illegal-migration-rises.

- “More for less? Europe’s new wave of ‘migration deals,’” European Council on Foreign Relations, October 8, 2018, https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_more_for_less_europes_new_wave_of_migration_deals.

- According to the European Commission, “the objective of regional disembarkation arrangements is to provide quick and safe disembarkation on both sides of the Mediterranean of rescued people in line with international law, including the principle of non-refoulement, and a responsible post-disembarkation process. Regional disembarkation platforms should be seen as working in concert with the development of controlled centres in the EU: together, both concepts should help ensure a truly shared regional responsibility in replying to complex migration challenges.” “Migration: Regional Disembarkation Arrangements: Follow-up to the European Council Conclusions of 28 June 2018,” European Commission, June 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20180724_factsheet-regional-disembarkation-arrangements_en.pdf.

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants, The New York Times, October 22, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html

- Human Rights Watch, “Algeria: Inhumane Treatment of Migrants: Pregnant Women, Children, Asylum Seekers Among Thousand Expelled to Desert,” June 28, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/28/algeria-inhumane-treatment-migrants.

- David Brennan, “Humans for Sale: Libyan Slave Trade Continues While Militants Kill and Torture with Impunity, U.N. Says,” Newsweek, March 21, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/humans-sale-libyan-slave-trade-continues-while-militants-kill-and-torture-855118.

- Jan Claudius Volkel, “Livin’ on the Edge: Irregular Migration in Egypt,” Middle East Institute, April 12, 2016, http://www.mei.edu/publications/livin-edge-irregular-migration-egypt.

- Ben Quinn, “Morocco rejoins African Union After 30 years,” The Guardian, January 31, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jan/31/morocco-rejoins-african-union-after-more-than-30-years

- https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/morocco-polisario-western-sahara-talks-an-ice-breaker-20181203

- Cecile Guerin, “Morocco’s ambitious investments in Sub-Saharan Africa full of risks and rewards,” Global Risk Insights,” May 26, 2017, https://globalriskinsights.com/2017/05/morocco-continues-to-invest-in-sub-saharan-africa/.

- Riccardo Fabiani, “Morocco’s Difficult Path to ECOWAS Membership,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 28, 2018, http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/75926.

- Ibid.

- Kirsten Schuettler, “A second regularization campaign for irregular migrants in Morocco: When emigration countries becoming immigration countries,” World Bank, January 13, 2017, http://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/second-regularization-campaign-irregular-immigrants-morocco-when-emigration-countries-become.

- Aida Alami, “Morocco Unleashes a Harsh Crackdown on Sub-Saharan Migrants, The New York Times, October 22, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/africa/morocco-crackdown-sub-saharan-migrants-spain.html

- Human Rights Watch, “Abused and Expelled: Ill-treatment of Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Morocco,” February 10, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/02/10/abused-and-expelled/ill-treatment-sub-saharan-african-migrants-morocco#.

Anna Jacobs

Anna Jacobs is an independent researcher based in Doha, Qatar. She currently works as the senior research assistant for the Brookings Doha center. She was formerly the Academic Director for the SIT Study Abroad program, Field Studies in Journalism and New Media, as well as a lecturer in politics and media at the Ecole de Gouvernance et d'Economie (EGE) in Rabat. She also worked as a freelance political risk consultant on Morocco and Algeria. Her research has primarily focused on politics in the Maghreb, democratization and political reform in the Middle East and North Africa, media and civil society, and migration, as a student at the University of Virginia, the University of Oxford, and as a Fulbright Scholar in Morocco. She was most recently published with Public Books, The Brookings Markaz Forum, Jadaliyya, and Muftah magazine.