Faced with EU’s incentives and pressure, Morocco seeks to strike a balance between cooperation and resistance on migration management.

Executive Summary

- Migration management and control have become defining elements of the EU’s relationship with its neighboring countries, especially those south of the Mediterranean.

- Migration is quasi-present in all EU external policies targeting third countries, especially those considered as major migrant sending and/or transit countries.

- Due to the geopolitical significance of Morocco’s location, the EU and its member states have devised several policy frameworks and provided financing and technical assistance to deepen their cooperation with Morocco on matters pertaining to migration management and border control.

- In recent years, Morocco has become active in combating the illegal migration of its own citizens and that of third country nationals that got enticed by the country’s geographical proximity with Europe.

- Morocco shares land borders with Spain as well as maritime borders, therefore, offering many seemingly easy points of entry to Europe.

- Yet, Morocco seems to be balancing its response to EU’s incentives and pressure by showing cooperation on border control and resisting proposals that it deems detrimental to its strategic interests.

Introduction

In the last two decades, migration management and security[1] have gained prominence in Morocco-EU multilayered, complex cooperation. The Rabat Process, a regional dialogue platform initiated in 2006 with the aim to involve countries of origin, transit, and destination in migration management, and the Mobility Partnership signed between Morocco and the EU in 2013, are good examples of this shift in priorities. Financial instruments such as the European Neighborhood Instrument (ENI), and the EU Emergency Fund for Africa, are also indicators of this shift in priorities from trade and diplomatic relations to security and migration management, which both are on the top of the agenda of the EU and its member states.

The EU has put in place policy frameworks and gave life to these policies through an array of financial instruments, with the aim to ensure that migrants are contained and kept as far as possible from its borders. Achieving this objective requires active participation of partner countries such as Morocco which, the EU and its member states, especially Spain, consider a key partner and a major player in the migration dossier.

The migration policies of the EU and its member states are turning Morocco into a de facto “Gendarme de l ’Europe,” a function that the country adamantly does not want to fulfill nor be identified with. Morocco’s position and sentiment in this regard, were clearly stated in 2013 by Mr. Saad Eddine El Othmani, the then Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (current head of government), when he unequivocally stated that Morocco refuses to be Europe’s gendarme.[2]Morocco’spolitical public position on this issue is disjointed from what is happening on the ground. EU pressure (political, economic, and financial) and the commitments of the country under the different cooperation frameworks with the EU and its member states, have, in fact, turned Morocco into the first line of defense against undocumented migrants.

This paper discusses Morocco’s role in curbing illegal migration to Europe and how EU’s policies, diplomatic and political pressure, and financial incentives are turning Morocco into a de facto gendarme of Europe.

Border Control, Surveillance and Management

Morocco’s experience with migration went through three stages in which the country played different roles depending on a set of factors. In the 1960s and 1970s, Morocco was a source country of migrant workers; hence it pursued an active policy of labor export.[3] This policy continued until Western European countries put restrictions on the migrant workers’ scheme in the mid-1970s. Then in the late 1990s, Morocco became the privileged transit platform for illegal migrants zeroing in on the European ‘Eldorado.’ And in the context of the enhanced border control and deepened migration cooperation between Morocco and the EU, mainly with Spain, the former has become a receiving country.

In contrast to Morocco’s evolving attitude toward migration, Europe’s stance on migration continues to drastically change, especially after the 2008 financial crisis which rocked many economic sectors in Europe. In particular, the sectors that employ low skilled workers (e.g., construction).[4] As a consequence, European governments adopted more restrictive policies and Europe’s public opinion became intolerant towards migrants. This development and the broad range of policies adopted by the EU under its Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM) turned Morocco into a country of destination in its own rights. Moreover, Morocco’s new status got confirmed after the country regularized the legal situation of thousands of undocumented migrants in 2014 and 2017.

The EU’s cooperation with Morocco on migration management and control, has many moving parts. Europe’s focus is on border control and management, and readmission agreements. On the former, Morocco has deep cooperation with the EU and its member states, namely Spain. In the latter, Morocco has concluded many bilateral readmission agreements with European countries such as Spain, France, and Germany. However, despite starting negotiations with the EU to conclude a EU readmission agreement (EURA) in 2000, these negotiations came to a halt in 2013.[5] In fact, the EU was unsuccessful in concluding an EURA with any of the Maghreb countries.[6] This failure, could explain the motives behind the EU’s 2018 disembarkation platforms proposal, which despite some enticing incentives could not gain momentum due to the strong opposition of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It seems that Maghreb countries saw in this proposal an unfair share of responsibility and a way for the EU to escape and deflect its international responsibility under international as well as European laws.

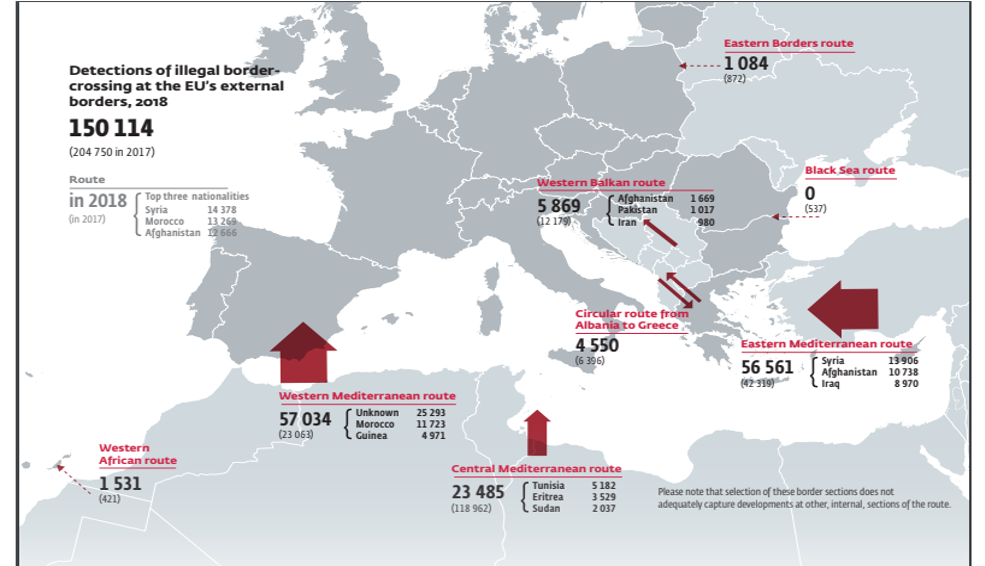

According to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX), 2018 has seen an increase in migratory pressure on Spain in which the number of detected illegal entries was doubled that of 2017. The same report indicated that departures from Morocco increased

fivefold during the same period, and that most of the migrants taking the West Mediterranean (WM) route came from sub-Saharan Africa in addition to a significant number of Moroccans (20.55% of the total entries).[7]This could be seen as the result of the spillover effect of the unstable situation in Libya and the Italian crackdown on migrants through its restrictive and repressive policies. These security and policy changes turned the West Mediterranean route into the most frequently used route in 2018,[8] and Spain into the main entry of undocumented migrants into the EU.

Source: FRONTEX 2019

This situation brought Morocco and Spain closer and deepened their cooperation on migration. Spain has become Morocco’s advocate in the EU, networking on behalf of the North African Kingdom to secure more funding under different EU’s financial instruments.[9]

In recent years, several high-level Spanish officials visited Rabat to meet their Moroccan counterparts to discuss matters of common interest with migration being top of the agenda. In 2018, for instance, Mr. Joseph Borrell, the then Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs said that: “immigration is a European problem that [Europe] will not be able to solve if we do not count on Morocco’s help.”[10]

It is evident that curbing migration requires a strong commitment from the Moroccan authorities which need to adopt policies and consecrate human and financial resources to effectively secure and control its terrestrial and maritime borders with Europe. However, Morocco seems to be in a delicate situation vis-à-vis its European partners, for the ‘migration problem’ that Europe, as stated by Mr. Borrell, wants to solve might become Morocco’s problem. In other words, the toughening of its border controls and their securitization means that more and more migrants would be trapped in Morocco. The increase in the number of migrants on Morocco’s soil is something that the Moroccan government wants to avoid because of its perceived economic and social ramifications. Would this explain why Morocco has not put in place the legal and institutional frameworks necessary for an effective migration policy and a working asylum system despite the recommendations of its human rights institution, the CNDH?

Morocco seems to be willing to cooperate with Europe on migration as long as this cooperation does not jeopardize its strategic interests nor put it in a situation where Europe’s responsibility is shifted to it, especially when, as indicated by Mr. Joseph Borrell, “Morocco is not well treated in terms of the aid granted by the European Union—for the fight against illegal immigration,”[11]

In comparison with the funds that Turkey was promised under the EU-Turkey Deal, Morocco is only receiving a small fraction. The magnitude of the numbers of migrants that Turkey hosts on its soil is a legitimate and plausible argument to support the financial preferential treatment bestowed on this country. However, Turkey’s economy is much bigger than that of Morocco, which struggles to provide economic opportunities even for its own people. This is one of the main reasons why more Moroccan youth is resorting to illegal migration. Moreover, most of those present in Turkey are from neighboring countries (mainly from Syria and Iraq) that share historical and religious ties with their hosts, and there is a big possibility that they will go back once the wars end.

In the case of migrants in Morocco, however, the situation is different, hence there is an unspoken fear of the gradual erosion of the so-called ‘Moroccan identity.’ Xenophobic attitudes towards sub-Saharan migrants are evidenced by the 2017 violent confrontations between young Moroccans and migrants in a neighborhood in Morocco’s biggest city, Casablanca.[12] Morocco is now facing challenges, and the resentment that some Moroccan youth have towards migrants is on the rise since they “see migrants as having everything easy.”[13]The way the media covers events about migrants particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa is also to blame for their negative depiction in society.

Direct Measures

To control its borders, Morocco needs considerable financial and human resources that the country lacks. Therefore, Morocco cannot afford to divert its scarce resources to fight illegal migration on behalf of the EU. Besides, fighting illegal migration is costly politically and financially, and Morocco seems to be not willing to risk its interests without receiving ‘a fair compensation’ in exchange from Europe.

In 2017 and 2018 Morocco was hit by two major social unrests in the city of Hoceima, North, and the former mining town of Jerrada, East of the country. These two cities are not major urban centers and are, indeed, located in the periphery of the country, however, the magnitude and longevity of the protests there are a strong indication of the social and economic malaise of Morocco. The government chose a repressive approach in dealing with the legitimate socio-economic demands of the residents of the two cities, which are still marginalized and economically not viable for their residents, especially to most of the youth who face bleak prospects.; hence, pushing thousands of young men and women to look for alternative ways to secure a better future for themselves and their families. This would also explain the exponential rise of Moroccan illegal migrants attempting to reach Europe in comparison to previous years. In 2018, Moroccans were the largest single nationality arriving in Europe through Spain.[14]

Morocco needs to create the right socio-economic, democratic, and institutional conditions to dissuade its citizens from attempting to cross to Europe illegally, as well as it needs to secure its borders to prevent the illegal migration of third-country nationals. This double function cannot be achieved without considerable resources that should not be mainly devoted to border control and neglect addressing the root causes of migration.

From 2014 to 2018, the EU disbursed Euro 232 million to fund 27 projects related to migration in Morocco.[15]A quick survey of these projects and that of the funds allocated to them reveal the following:

- Morocco holds the largest cooperation portfolio amongst North African countries.

- EU-Morocco cooperation on migration is financed through mainly three financial instruments: The EU Emergency Fund for Africa (EUTF Africa) created after the EU-Africa Valetta Summit, European Neighborhood Instrument (ENI), and the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI)

- Most of the funds, that is, 73% (Euro 170 million) go towards border management and the fight against human trafficking and smuggling, and the remainder of these funds is geared towards socio-economic integration (4%), protection (10%), and governance and migration policy (13%).

- Most of the project implementers are either Moroccan state institutions or European NGOs and EU member states development agencies (e.g., Spanish, German GIZ, French AFD), and UN specialized agencies (e.g., UNICEF, UNHCR, IOM). Only five Moroccan NGOs are among the list of implementers. This situation would be counterproductive in the long run because Moroccan NGOs will not develop their capacity nor be effectively involved in finding solutions and facilitating the integration of migrants if they continue to be deprived from funding, which is very crucial and indispensable in every field.

As was highlighted above, most of EU funding to Morocco goes towards border management and control. This is a clear indication that the EU supports the Kingdom’s repressive approach to migration and that the securitization of borders is the predominant response to migrants’ influx. Besides, there have been media reports that Morocco has requested60 million euros in additional funding from its EU partners to buy high-tech surveillance equipment such as radars, scanners, helicopters, and other gear for its security agents in charge of border control.[16] It is reported that the Moroccan authorities sent the list of the aforesaid equipment to the Spanish government which in turn sent it to the European Commission.[17]

There is, indeed, close operational cooperation between Spain and Morocco. The two countries conduct joint patrols at sea, share information gathered through radars, satellites, and drones about the movements of undocumented migrants either at sea or in the forests surrounding the two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. The enhancement of Spain’s monitoring capabilities of its coastlines after it deployed in the mid-2000s the External Surveillance Integrated System (SIVE) has also contributed to intelligence sharing between the two parties, which is necessary for their joint fight against human traffickers as well as migrants and narcotics smugglers.[18] The two countries even work together, sometimes, to circumvent European and international law through their cooperation on ‘hot returns’ at the buffer zone between the fences surrounding the two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, where migrants are reportedly held until Moroccan border control agents arrive to take them back to Morocco.

Spanish – Moroccan bilateral efforts are supplemented by EU resources. The border control and surveillance between the two states are partially EU-funded and reinforced through FRONTEX’s two main operations in the Western Mediterranean, Minerva and Indalo.[19] The main objective of these operations is to assist national authorities in their fight against illegal migration and drug trafficking. They provide information and conduct rescue missions at sea. There are, in fact, 180 officers from several EU member states helping the Spanish authorities to, inter alia, fight criminal smuggling networks, register migrants, and conduct border checks.[20]

Border control and surveillance are done through multilayer cooperation between Spain, Morocco, and the EU. Each of these three actors seems to have a particular task to fulfill. Morocco, for instance, is apparently tasked with taking all the necessary preventive and precautionary measures to dissuade migrants from approaching the popular illegal migration hotspots. Spain then intervenes as a second line of defense, by providing technical support and some funding to their Moroccan counterparts, then the EU joins the efforts of the two countries by providing financing, political and diplomatic support, as well as institutional policies and legal frameworks to facilitate the fight against illegal migration which, is not always done in total respect of the basic human rights of migrants.

Indirect Measures

Under the impulse of its EU partners,[21] Morocco uses other means to curb illegal migration. Moroccan authorities have made northern cities like Nador and, to some extent, Tangier and Tetouan off-limits even to sub-Saharan migrants who acquired legal status after the two regularization campaigns in 2014 and 2017.[22]The Nador branch of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH) frequently reports on the illegal arrests,[23] detention, and displacement of sub-Saharan migrants from Nador and towns around it. The same NGO has criticized the authorities on numerous occasions for the detention conditions of migrants, especially vulnerable groups such as women and minors.

The arrest of sub-Saharan migrants is mainly based on racial profiling,[24]as it is reported by GADEM, AMDH, and others. Moroccan security agents arrest migrants from Africa even when the arrested person is legally residing in the country. Reports talk of arrests taking place in hospitals, markets, streets, and anywhere a ‘black person is seen.’[25] The authorities’ conduct is a clear violation of the country’s constitution which prohibits discrimination based, inter alia, on race, color, and national origin. With this conduct, Morocco is also violating the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), which the country ratified on December 18, 1970.

Morocco also uses forced displacements of migrants from the northern cities to fight illegal migration. Displacing potential illegal migrants as far as possible from the two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, and from Moroccan coastal cities known to be the point of departure for boats carrying illegal migrants, has become one of Morocco’s special techniques. This technique does not differentiate between migrants legally residing in the country and those that are undocumented. Forcefully displacing people is against the right of free movement enshrined in the 2011 Constitution (art. 24). Furthermore, it causes migrants a lot of psychological and material damage like loss of property and separation from loved ones, to cite a few.[26]

There are instances where Morocco has used administrative barriers to create unbearable conditions for migrants to make them reconsider their plans to settle in northern ‘hotspots’ such as Nador and the towns and localities in its vicinity. For instance, during the regularization campaigns, 278 applications filled out by sub-Saharan migrants in the northern city of Nador were rejected. The two applications that were approved out of the 280 that were filled out belonged to migrants from the Middle East.[27] It is noteworthy that the populations living in Moroccan cities adjacent to the two Spanish enclaves have, based on agreements between Morocco and Spain, the right to enter these two enclaves without a visa; and only with an identification card showing residency in one of these towns. Perhaps this is why the Moroccan authorities did not approve the regularization requests made by sub-Saharan migrants in Nador for this might have given them access to Melilla, and therefore, a foot on EU territory or at least kept them closer to Europe’s borders.

Using its strategy of direct and indirect migration control mechanisms, Morocco managed, according to its Minister of Interior, in 2018 alone to foil 89,000 illegal migration attempts, dismantle 229 migrant trafficking networks, and rescue 29,715 migrants at sea.[28] However, has this elaborate toolkit of border control techniques and the so-called long and ‘model’[29] cooperation between Spain and Morocco brought down the number of illegal entries into EU territory?

The Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS) found that in the period 2008 – 2015,[30] the number of illegal border crossings was on the rise almost every single year, and that despite deep bilateral cooperation between Spain and Morocco, and the EU support through funding and advanced surveillance through, inter alia, the European Border Surveillance System, EUROSUR.[31]

The survey of the illegal crossings of migrants through the Western Mediterranean route for the period 2015 – 2018 confirms the previous findings; and shows that despite all the efforts deployed (financial, political, and human costs), the fight against illegal migration, as evidence shows, is failing.

Table 1: Illegal crossings by year on all Mediterranean routes.

| Year | Eastern Mediterranean (EM) | Central Mediterranean (CM) | Western Mediterranean (WM) | Share of WM irregular crossings in total. |

| 2015 | 885,386 | 153,946 | 7,004 | 0,67% |

| 2016 | 182,277 | 181,376 | 9,990 | 2,67% |

| 2017 | 42,319 | 118,962 | 23,063 | 12,51% |

| 2018 | 56,561 | 23,485 | 57,034 | 41.6% |

Source: Data compiled by the author from FRONTEX statistics.

These findings prove that, in spite of all the high-tech surveillance, joint patrols, and the fencing off of Ceuta and Melilla, the borders between Spain and Morocco are difficult to seal off. The number of illegal crossings has more than doubled each year since 2016 and migrants still find ways to circumvent these measures and reach Europe. Unfortunately, to circumvent Moroccan and Spanish border controls, migrants do resort to dangerous ways, hence the increasing number of recorded deaths.

Table 2: Total deaths by year on all Mediterranean routes.

| Year | Total Death of Migrants (EM, CM, WM) | Western Mediterranean | Share of Deaths in Total |

| 2014 | 452 | 19 | 4.20% |

| 2015 | 2,103 | 38 | 1.80 |

| 2016 | 2,911 | 86 | 2.95% |

| 2017 | 2,155 | 69 | 3.20% |

| 2018 | 1,177 | 293 | 24.89% |

| 2019 (January – June) | 597 | 201 | 33.67% |

Source: Data compiled by the author from IOM website: missingmigrants.iom.int

The findings above show the limits of a security-driven approach as well as the human cost of these measures. Therefore, it is time for Europe to think of innovative and humanistic ways to tackle illegal migration instead of ‘throwing more money at the problem,’[32] and causing tragedies at sea and land borders.

In order for migrants to reach Morocco they need to transit through other countries, therefore, it is important to involve these countries in the fight against illegal migration. The EU Commission seems to have come to this conclusion. In its 2019 report to the EU parliament and Council, the Commission concluded that: “Addressing migratory flows and tackling smuggling routes towards Morocco from its neighbors should also be part of this closer cooperation.”[33]

It is time to see illegal migration through a multi-colored lens rather than through a security prism per se. As has been highlighted in other studies,[34] the mainstream media and policy discourse in Europe persist in advocating for a security-driven approach to migration. Would other voices rise and propose other alternatives, especially now that the focus on border control has proven to be limited and costly in financial terms as well as in human lives?

Readmission

The other major aspect of EU-Morocco cooperation on migration is readmission. Morocco has signed readmission agreements with some EU member states as early as 1992, and started negotiations on a EURA since the 2000s. The negotiation between the EU and Morocco on this mechanism of migration control has come to a halt in 2013. Bilateralism is the path that Morocco and its European partners seem to prefer when it comes to the readmission of Moroccan nationals as well as third country nationals (at least in the case of Spain).[35]

Bilateral Readmission Agreements

The first readmission agreement between Morocco and an EU member state that comes to mind, is the Agreement Between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Morocco on the Movement of People, the Transit and Readmission of Foreigners who Have Entered Illegally (readmission agreement) signed in 1992.[36]This agreement has come to the forefront in recent years, especially in the context of the increasing fight against illegal migration and the human rights violations that occurred in this context. The illegal pushbacks or hot – returns from the two Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, are violations of international law as well as European law, namely the European Convention on Human Rights, as has been exemplified in the emblematic ECtHR case of N.D and N.T v. Spain.[37] The case of Doumbe Nnabuchi v. Spain which is still pending before the ECtHR proves that pushbacks are not isolated but used systematically.

The Spanish government invokes its readmission agreement with Morocco to legitimize its actions. So, what is the particularity of this agreement?

The main particularity of this agreement, which came into effect on 21 October 2012,[38] is that it responds to the issue of the readmission of third country nationals (TCN). This clause that most transit countries south of the Mediterranean seem not to be inclined to incorporate in their agreements with European countries is the raison d’être of the Spanish – Moroccan agreement; and thus far, it is the only agreement where Morocco accepts to readmit third-country nationals. However, this agreement targets sub-Saharan African migrants as it excludes in its article 8(e) the expulsion of illegal migrants from the Maghreb States.

Morocco had also concluded arrangements with Spain for the repatriation of thousands of unaccompanied Moroccan minors present either in the two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla or on the Spanish mainland. This step caused the outrage of human rights NGOs which saw in this agreement an infringement on the rights of these minors.[39]

Morocco was also cooperating with Germany on the return of thousands of Moroccan nationals whose applications for international protection were denied, and with France which, in recent years returned 1,161 of undocumented Moroccan migrants with a staggering cost of 171 million euros .[40]

Furthermore, other studies show that Morocco is not reluctant in its cooperation with member states when it comes to the readmission of Moroccan nationals. A study carried out by the Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and commissioned by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung’s North African Office in Rabat found that there were instances where the identification and issuance of travel documents by Morocco’s consular services were done in a faster pace than the steps taken by the requesting state.[41] One aspect of the return policy that Morocco does not seem to be keen about is the use of charter flights, something that the Algerian authorities are also against. Tunisia, however, does not seem to have a problem with the use of charter planes when returning its citizens.[42]

Bilateral readmission agreements between Morocco and several EU member states are operational and seem to be increasingly used despite some practical barriers such as the localization of individuals to be deported, and the reintegration of those readmitted into the country’s social fabric. Leaving illegal migration drivers and push factors unaddressed is what keeps the vicious cycle of illegal migration turning. A recent study by the Arab Barometer for the period fall 2018 – Spring 2019 revealed that an alarming number of youth from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) wish to emigrate to one of the developed countries.[43] The case of Moroccans is quite alarming for over 43% of youth surveyed wish to leave the country as soon as an opportunity presents itself. These findings should inform policymakers and politicians to rethink their strategies and overhaul EU’s external policy on migration. Working on developing partnerships to create opportunities for the disenfranchised youth and to promote the necessary conditions for a real democracy and rule of law might be the solution.

EU Readmission Agreement: Disjointed Expectations?

The negotiations between the EU and Morocco on an EURA started in the early 2000s, and continued until 2013 where, after more than 15 rounds of negotiations, it came to a halt. The signing of the 2013 Mobility Partnership between the EU and Morocco left the door open for further negotiations on an EURA. The Commission concluded in its 2011 evaluation of EURAs that: “If a TCN clause was not demanded by the EU or was underpinned with appropriate incentives, some negotiations [e.g., Morocco, and Turkey] could have been concluded already.”[44]

EU member states see that the added value of an EURA with Morocco is in the inclusion of a TCN clause. Morocco adamantly rejects the TCN clause for practical reasons as well as political ones. On the practical side, Morocco sees that it would be quite difficult, if not impossible, to prove that a migrant transited through Morocco or not (e.g. What kind of proof could be considered?).[45]On the political side, Morocco apparently sees in an EURA a way through which the EU wants to transfer its problems to other countries. Furthermore, the TCN clause may prove too costly, both financially and politically. On the political side, Morocco will appear as a country that ‘subcontracts dirty jobs’ from Europe, and this will be detrimental to its public image in Africa especially in the context of its ‘politique Africaine.’[46] On the financial side, readmitting third country nationals means that Morocco needs to build its reception infrastructure, and negotiate as well as offer financial incentives to African countries to readmit their nationals.

Moroccan officials legitimately ask why EU member states do not conclude readmission agreements with the African countries whose citizens are illegally residing in Europe instead of concluding an EURA with Morocco that includes the contentious TCN clause?[47]

A plausible answer to this question could be that most member states’ decisions concerning return go through administrative as well as judicial reviews, which slow and sometimes even annul such decisions. In fact, the recast EU Asylum Procedures Directive (2013/32/EU) sets appeal procedures including the right to an effective remedy.[48] Furthermore, certain EU member states use the concept of ‘safe countries of origin’ in their review process of asylum applications.[49] According to this concept, a country is considered safe if it has a democratic system and consistently there is no persecution as defined in article 9(2) of Directive 2011/95/EU,[50]“no torture or inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment, no threat of violence, and no armed conflict”.[51]Most sub-Saharan African countries are not considered safe countries of origin by most EU member states. This means that the removal of these undocumented migrants from Europe would be challenging. Therefore, an EURA with Morocco that includes a TCN clause seems to be what member states see as the adequate solution.

Conclusion

Morocco faces increasing pressure “from Europe in matters relating to migration governance, in light of the geopolitical significance of the Kingdom’s location.”[52] Nonetheless, Morocco should not succumb to these pressures, nor should it hide behind Europe’s pressures to not respect the human rights of migrants and not fulfill its conventional responsibilities. Morocco needs to take proactive steps and stand its ground as it did when it rejected EU’s “regional disembarkation” proposition.

Morocco cannot pretend to be a major player and champion of a critical dossier such as migration, without building its own adequate migration framework. Hence, it needs to complete its legal and institutional protection systems and bridge the gap between law and practice. It is important to keep in mind that laws are merely texts on paper if they are not implemented and effectively enforced. It is time for Morocco to effectively implement the laws it has already enacted and expedite the creation of those it lacks to build its protection machinery. The incomplete protection system it has, is insufficient and inconsistent with Morocco’s political stance and its promises under its National Strategy on Immigration and Asylum. Furthermore, Morocco’s 2011 Constitution enshrined the supremacy of international conventions over national legislation. This is a laudable development; however, it will remain lettre morte if Morocco does not align its legislation with international law, especially the treaties it has ratified, likewise, if it does not train judges and law practitioners to apply treaties when litigating a case or rendering a verdict on one. Morocco also needs to strengthen its judiciary system to ensure that the right to an effective remedy is attainable in practice.

Furthermore, if Morocco is serious about improving its human rights record and ensuring that the human rights of persons under its jurisdiction are fully respected, then it needs to effectively adhere to UN and regional treaty bodies by submitting its reports on time and accepting individual complaints procedures. This would offer venues for its citizens and those under its jurisdiction to protect their rights. Morocco also needs to join the African Union’s human rights mechanisms, particularly, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. This would ensure some accountability as a system without accountability is a system that encourages abuses.

Concerning the European Union, this institution must be realistic and humanistic when drafting and implementing its migration control policies. It would be judicial to conduct an impact assessment of these policies and to make sure that their application would not engender any human rights violations. The EU needs also to create monitoring bodies to ensure that migration control is done in total respect for the rights of migrants, and to work with countries of origin and transit on sustainable solutions and pathways that open Europe’s doors to those in need of protection. Transferring the burden or delegating border control to third countries is not the solution.

Footnotes

[1] Chloe Teevan (2019), EU-Morocco: a win-win partnership? Moroccan Institute for Policy analysis. Retrieved June 07, 2021. https://mipa.institute/jorifiq/2019/06/Chloe-Teevan-English-.pdf

[2] Statewatch News Online: (2013). Retrieved June 16, 2019, from http://www.statewatch.org/news/2013/mar/05eu-morocco.htm

[3] Bel-Air, F. D. (2016). Migration Profile : Morocco. 16.

[4] The so-called migration crisis of 2015 reinforced Europe’s fear of migrants.

[5] Carrera, S. al (2016, January 22). EU-Morocco Cooperation on Readmission, Borders and Protection: A model to follow? [CEPS]. Available at: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/eu-morocco-cooperation-readmission-borders-and-protection-model-follow/

[6]Abderrahim, T. (2019, January 15) Pushing the boundaries: How to create more effective migration cooperation across the Mediterranean. (2019). Retrieved from: https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/pushing_the_boundaries_effective_migration_cooperation_across_Mediterranean

[7] See FRONTEX (2019), “Annual Risk Analysis of 2019”, Warsaw, P. 6. Available at: https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis_for_2019.pdf

[8] Ibid, P. 8

[9] Bazza, T. (2018, October 18). Spain Calls for Raising EU’s Fund to Morocco for Border Control. Retrieved June 18, 2019, from Morocco World News website: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2018/10/255651/spain-calls-for-raising-eus-fund-to-morocco-for-illegal-immigration/

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, (2018), Evaluation of the Partnership for Democracy in Respect to the Parliament of Morocco, available at: http://website-pace.net/documents/18848/4457779/20180911-MoroccoPartnerDemocracy-EN.pdf/f922662b-60b2-4e39-8726-aaff08e3c931 (P 11, pp 63)

[13] Ibid

[14]Communication From The Commission to The European Parliament, The European Council, and The Council (2019), “Progress report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration”, available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20190306_com-2019-126-report_en.pdf

[15] For more details see the factsheet of the EU cooperation on migration with Morocco available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/eu-morocco-factsheet.pdf

[16] Kasraoui, S. (2018, July 28). Morocco Asks Spain for €60 Million to Fight Undocumented Migration. Retrieved June 19, 2019, from Morocco World News website: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2018/07/251326/morocco-spain-e60-million-fight-undocumented-migration/

[17] Ibid

[18] Carrera, S. al. (2016)

[19] Ibid

[20] For more detail about FRONTEX main operations, please see https://frontex.europa.eu/along-eu-borders/main-operations/operations-minerva-indalo-spain-/

[21] Through financial and political support, the EU and its member states seem not to take the respect of human rights at heart when it comes to the so-called fight against illegal migration.

[22]Morocco’s Strategy on Immigration and Asylum was put in place in 2014 as a response to the CNDH’s critical report on the situation of migrants, and to the responsiveness of the Moroccan Monarch towards its recommendations thereof. Consequently, Morocco launched two regularization campaigns, the first in 2014 and a second in 2017. These campaigns received a lot of media coverage by the authorities as being innovative, and humanistic in their approach. Emphasis was put on the fact that Morocco’s initiative was the first in the region and that the country is mindful of the rights of migrants and that it does all it could to facilitate their integration despite the country’s limited resources.

[23] AMDH Nador (2018), « La Situation de Migrants et Refugiés à Nador », Retrieved on 15 June 2019 from : http://amdhparis.org/wordpress/?p=4645

[24]Active identity checks / profiling of sub-Saharan Africans occurs mainly in cities like Tangier and Nador whereas almost no identity checks are conducted in other cities.

[25] AMDH Nador (2018) and GADEM (2018)

[26] Ibid

[27] Ibid

[28] VOA News, 2019, Report: Morocco Foils 89,000 Illegal Migration Attempts in 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2019, from : https://www.voanews.com/a/morocco-foils-89-000-illegal-migration-attempts-in-2018-interior-ministry-reports/4747825.html

[29] Carrera, S. al (2016, January 22). EU-Morocco Cooperation on Readmission, Borders and Protection: A model to follow? [CEPS]. Available at: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/eu-morocco-cooperation-readmission-borders-and-protection-model-follow/

[30] Ibid

[31] More details about this border surveillance system can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/border-crossing/eurosur_en

[32] Carrera, S. al (2016, January 22).

[33] Communication from The Commission to The European Parliament, The European Council, and The Council (2019), “Progress report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration”

[34] See Carrera, S. al (2016, January 22).

[35]Money, J., & Lockhart, S. (2018). Migration Crises and the Structure of International Cooperation. Athens: University of Georgia Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt22nmcdt

[36] The English version of the agreement is available at: https://therightsangle.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/19920213-spain-morocco-readmission-agreement-eng.pdf

[37] ECtHR Grand Chamber, however, determined on February 13, 2020, that Spain did not violated the ECHR. See https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/cp_spain_eng.pdf

[38] See Submission by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the cases of N.D. and N.T. v. Spain (Appl. Nos 8675/15 and 8697/15) before the European Court of Human Rights, available at: https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1424631/1226_1518764566_59d3a81f4.pdf

[39] Eliason, M. (2019, April 25). Spain Prepares to Repatriate Unaccompanied Moroccan Minors. Retrieved June 25, 2019, from Morocco World News website: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/04/271426/spain-repatriate-unaccompanied-moroccan-minors/

[40] LAKHDAR, Y. (2019) (French Authorities Deported 1161 with a Cost of Euro171 Million) ا لسلطات الفرنسية تُرحل 1161 مهاجراً مغربياً بـ171 مليون درهم. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from: https://www.hespress.com/societe/434677.html

[41] CEPS, 2017, ‘EU and German External Migration Policies: The Case of Morocco’, Rabat, Morocco. https://ma.boell.org/sites/default/files/eu_and_german_external_migration_policies_-_ceps.pdf

[42] Abderrahim, T. (2019)

[43] BBC News, (2019, June 27). Arab uprisings: Which country could be next? Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48771758

[44] Commission (2011b), “Communication – Evaluation of EU Readmission Agreements”, COM (2011) 76 final. P. 9. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-is-new/news/pdf/comm_pdf_com_2011_0076_f_communication_en.pdf

[45] Carrera, S. al. (2016)

[46] BALDE, O. (2017) ‘La politique africaine du Maroc expliquée par Bourita.’ Le Soir Economic Maroc, Retrieved June 28, 2019, from https://www.leseco.ma/les-cahiers-des-eco/afrique/58136-la-politique-africaine-du-maroc-expliquee-par-bourita.html

[47]den Hertog, L. (2016). Funding the eu–Morocco ‘Mobility Partnership’: Of Implementation and Competences, European Journal of Migration and Law, 18(3), 275-301. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12342103

[48] Directive 2013/32/EU of the EU Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection.

[49] European Migration Network (2018). Safe Countries of Origin – EMN Inform. Brussels: European Migration Network. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/00_inform_safe_country_of_origin_final_en_1.pdf

[50] Directive 2011/95/EU of the EU Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on common on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for persons eligible for subsidiary protection, and for the content of the protection granted (recast).

[51] See EU ‘Safe Countries of Origin’ List available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/background-information/docs/2_eu_safe_countries_of_origin_en.pdf

[52]OHCHR. (2018, December 21). End of Mission Statement of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance at the Conclusion of Her Mission to the Kingdom of Morocco. Retrieved July 13, 2019, from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24043&LangID=E

Mustapha Hadji

Mr. Hadji holds an MA in Global Affairs from George Mason University – USA. While in the United States, Mustapha worked, for 5 years, as an adviser at an Arab Embassy in Washington DC. Then, an Africa researcher with a USG contractor in Virginia. And for the last 3 years, a field protection delegate (in several African countries) with a prominent international organization. Mustapha’s research interests include African Affairs, conflict resolution, and Human Rights and Democratization.