[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This study attempts to shed light on Moroccan Salafis’ perception of themselves and their Social and Political Environment.

Introduction

The transformations within the Salafi movement after the Arab Spring have generated considerable attention among scholars and policymakers alike, particularly concerning the relationship between Salafism and violent extremism, among other issues. Yet, while most of the studies have relied on secondary sources and qualitative data, research that relies on primary sources, namely those that scrutinize Islamists through quantitative analysis, remains scarce. Some studies have sought to investigate violent extremism by creating a database that monitors the activities of armed groups and terrorist operations[1]. Those studies, however, did not explore representations and perceptions of ordinary Salafi activists.

In this regard, two factors explain why Salafism has resisted quantitative analysis. The first is related to the difficulty in measurement of data. Questions on extremism and moderation are both contextual and relative. What is perceived by some as indicators of extremism, is perceived by others as part of their religious identity. Moreover, the Salafi phenomenon is a complex one that is difficult to analyze and package into ready-made templates. This had led some researchers[2] to stress the difficulty of relying on quantitative analysis to explain the factors that make individuals vulnerable to extremism[3]. The second factor is related to the studied population. Salafi groups are a particular sector in society that is hard to reach and persuade to participate in a study. For example, Mohammed Abu Rumman, a prominent scholar on Salafism and current Minister of Culture and Youth in Jordan, attempted to carry out quantitative research with young Salafis in a book that analyzed the formation of a quietist Salafi identity in Jordan in 2014. In the book, he tried to conduct an opinion poll, but his attempt failed due to the Salafis’ refusal to take part in the survey[4].

Instead of targeting a general public, this report focuses on quietist Salafis in Morocco. It should be noted here the difficulty of using objective instruments to measure the attitudes of Salafis on different issues. To reach this goal, we have developed a set of interrelated indicators to monitor representations and attitudes of quietist Salafis on various issues, ranging from political activism to violence and trust in institutions, as well as indicators of religious knowledge and interaction with modern media. The questionnaire consists of about 70 indicators to measure attitudes, representations, and behavior. Questions analyzes attitudes towards current, local beliefs and everyday behavior alongside international religious and political issues.

In practical terms, we have relied on key indicators that, in turn, consist of a set of sub-indices:

- First indicator: includes religious knowledge and its sources. We considered how an increased awareness level of knowledge sources outside Salafi references, translated to an increased ability to accept new ideas and the belief in the relativity of knowledge. Meanwhile, Salafis who are closed off to other knowledge sources, and limited only to Salafi references, are more likely to be limited in their openness to new ideas, which in turn leads to ideological intolerance.

- Second Indicator: Salafis and means of communication. This is an analytical-descriptive chapter of the Salafis’ relationship with modern means of communication, how they invest them, and how they are influenced by them.

- Third Indicator: Salafis’ political participation and their electoral orientation.

- Fourth Indicator: Salafis’ attitudes towards society, Sharia, and everyday behavior, as well as their readiness to accept engagement in society and interact with its various components. This indicator also encompasses attitudes towards other everyday matters such as dealing with conventional banks in times of necessity.

- Fifth Indicator: Salafis’ attitudes towards armed violence and support for the Syrian revolution and foreign fighters.

- Sixth Indicator: The issue of coexistence with the other and trust in institutions. The Salafi respondents were asked to determine their positions vis-à-vis twenty-seven political, religious, and civil institutions.

Methodology

The data presented in this report is based on fieldwork studies carried out between 2013 and 2014 targeting 150 active members of the quietist Salafi trend, especially members and frequenters of Salafi Houses of Quran, which are close to Cheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Maghraoui and Sheikh Hammad Kabbaj[5]. The field research was completed in two stages: the first phase was completed in September 2013, the period in which about 70 questionnaires were completed. The remaining questionnaires were completed between March and June 2014. We distributed 150 questionnaires to Salafis and we were able to complete 114 of them in face-to-face meetings with respondents. Ten questionnaires were completed independently by the respondents and then sent to us[6].

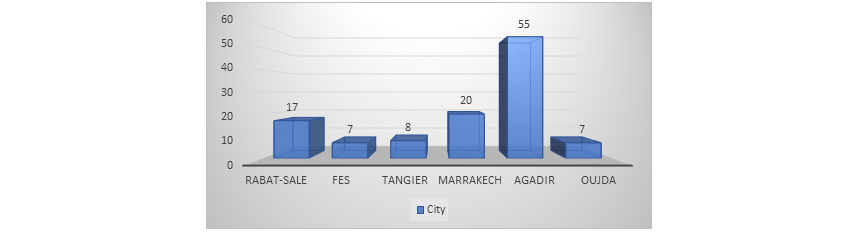

With respect to geographical distribution, approximately 50 % of respondents were from Agadir, 20 % from Marrakech, 17 % from Salé, and the remaining 7 % from the cities of Fez, Tangier, and Oujda. This distribution reflects the distinct Salafi presence within these cities, and the large sample from Agadir demonstrates how the city is home to a number of “quietist” Salafi.

Figure 1: Respondents’ Geographical Distribution

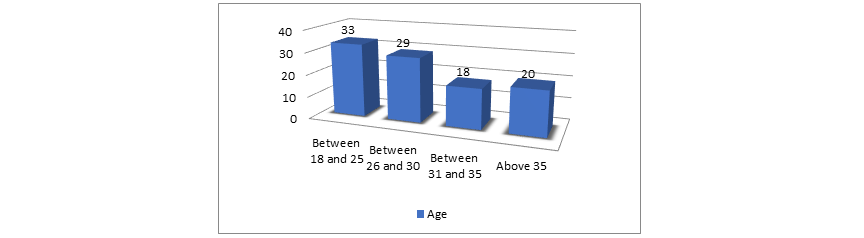

The sample is also characterized by youth characteristics at several levels. In terms of age, respondents ranged from eighteen to fifty-four years. Eighty % of respondents were below thirty-five, while those between eighteen and twenty-five represented about one-third of the sample. However, the characteristics of the sample may not be representative of the general Salafi trend in Morocco due to the absence of a statistical base on which to rely. We note that the predominance of youth in the sample may not accurately express the age division within the Salafi current[7].

Figure 2: Respondents’ Age Distribution

With respect to marital status, half of the sample responded that they were married, while the other half were still single. The vast majority live in ordinary or traditional homes or village houses, while a small proportion live in medium or high-quality buildings or villas. Professionally, one-third of the respondents are students, while the remainder work in trade occupations or independent and liberal professions. The number of employees does not exceed one-tenth of the persons surveyed. As for the level of education, about one-quarter of the respondents have university degrees, while about 20 % of them have high school diplomas. Notably, about 14 % of the respondents had only a Qur’anic education and did not receive a formal education.

Figure 3: Educational Background

Figure 4: Marital Status

Figure 5: Professional Activity

Salafis’ Religious Knowledge

Salafis greatly value the traditional religious knowledge produced by Salafi scholars and perceive it as a key input to proper creedal formation. Due to their interest in obtaining evidence before an opinion is accepted and having evidence before judgement, a Salafi is not concerned with Taqlid, adherence to tradition. Instead, he is concerned with a practice called Itibaa’, or the formal and substantive obligation to precedent, also known as the Salaf.[8] In this sense, every Salafi activist is freed from the yoke of strict adherence and is faithful to the true teachings of the early generations of Islam. Ironically, Itibaa’ is in itself a form of adherence to the traditions of predecessors (Taqlid) by literally taking religious knowledge and beliefs from them. It is also the gateway to many divisions because of the multiplicity of interpretations of religious texts. In any case, Salafis are keen to glorify Salafi religious knowledge in large measure because it endows those who master Islamic sciences with prestige and legitimacy in the eyes of those affiliated with the movement.

In general, there are three sources of religious knowledge:

- The first method is traditional and relies on listening and memorization. It is mainly related to religious lessons delivered by Salafis in mosques or in the houses of the Quran. This method has been in practice since the dawn of Islam through Dhikr Circles and lessons in mosques.

- The second method depends on reading heritage books.

- The third method depends on remote access to religious knowledge through satellite TV, without the need for traditional religious mediators. Due to the emergence of satellite channels and modern communication technology, the relationship with religious knowledge has changed–its production is no longer confined to the sacred spaces that the mosque embodied. It is no longer restrained to official or traditional scholars, and religious discourse is freed as a result of the liberalization of the media space in the Arab world.

It is therefore important to identify Salafis’ sources of religious knowledge. This report sought to do thus by collecting this information during field research. The questionnaire focused on access to these sources, the relative importance of religious figures and their impact on respondents, the types of books respondents consumed, and the satellite TV channels and social media sites that the respondents followed.

At first, we wanted to explore the Salafis’ treatment of written Salafi references. The interaction with the written texts reflects an in-depth level of intellectual association with a particular ideology. The type of books being read also reflects the reader’s priorities and intellectual interests. Questions were asked concerning the pace of reading, the type of the books that were read, and the written references that the respondents relied on in building their intellectual perceptions.

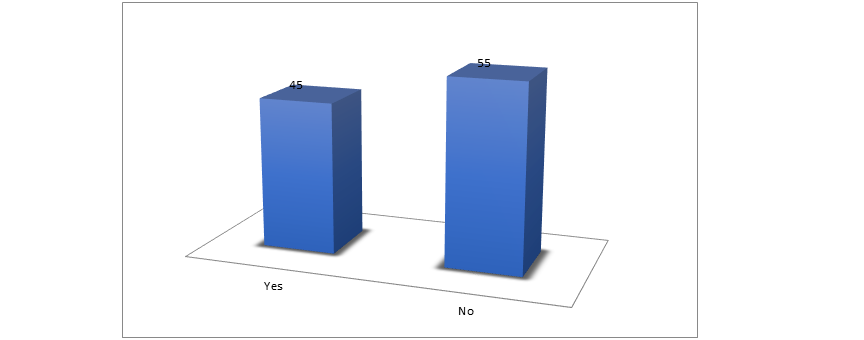

Figure 6: Reading a book during the last three months

As for the question about the pace of reading, a closed question was asked about whether the respondent had read a book during the last three months. More than half of respondents had not read any books in the past three months. Those who did not read were satisfied by the religious lessons delivered in Quranic houses or in mosques or by viewing shows on satellite channels. Respondents who answered the question in the affirmative, meanwhile, were asked to name the books that they read, resulting in a list of heritage books, especially those explaining the Hadith, such as Kitab at-Tawhid (The Book of the Oneness of God) by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Fatawas of Shaykh Ibn Taymiyyah, and the book of Fiqih Sunnah of Sayyid Sabiq.

Table 1: List of reference books read by the respondents during the past three months[9]

| Book title | Author | Frequency | |

| 1 | Sahih al-Bukhari | Imam Muhammad al-Bukhari | 12 |

| 2 | Sahih Muslim | Imam Muslim | 11 |

| 3 | Kitab at-Tawhid | Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab | 11 |

| 4 | Fiqih Sunnah | Sayyid Sabiq | 7 |

| 5 | Riyadh as-Salihin | Imam An-Nawawi | 4 |

| 6 | Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum | Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri | 4 |

| 7 | Al-Nawawi’s Forty Hadith | Imam Nawawī | 3 |

| 8 | Al-Muwatta | Imam Malik | 3 |

| 9 | Commentary on the Forty Hadith of Al-Nawawi | Aḥmad Ibn al-ʻImād al-Aqfahsī | 3 |

| 10 | Al-Usool-uth-Thalaatha (The Three Fundamental Principles) | Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab | 3 |

The question of what books the respondents read played an important role in determining the references that shaped their ideologies, as well as determining the jurisprudential and doctrinal characteristics in the most widely read books. In addition to Hadith and Sunnah books such as Sahih Bukhari and Muslim, we also find the book of Kitab at-Tawhid by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, which contains ideas of “religious reform” by determining the nature of the overlap of disbelief and Shirk, according to his belief in the practices of worship, and directed to the correct doctrine free from “heresy (bid’ah) and innovation”. The results also included the existence of other books, such as Fatwas of ibn Taymiyah, Fiqh of the Sunnah, Riyad Al-Salihin, and the Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum of Ibn Al-Qayyim and others.

Although only about half of the respondents responded in the affirmative to the question of reference books, a small %age of them were able to identify three books that they had read during the last period. Most of those who responded only mentioned a book or two at most. Despite this, we were able to identify more than forty titles, all of which belong to the heritage books adopted by the Salafi trend.

From a quantitative perspective, three books appeared at the top of the books read by the respondents during the last three months. The book of Sahih Bukhari took precedence having been cited 12 times, followed by the book of Sahih Muslim and Kitab at-Tawhid by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab with 11 recurrences each. The %age of the repetition of these books reflects the relative importance of these books for Salafis. The Book of Sahih Bukhari is considered the first source of authentic Hadiths transmitted by the Prophet for the Sunnis (Ahl al-Sunnah) and it contains about 4,000 Hadiths, followed, in order of importance, by Sahih Muslim,[10]Al-Bukhari, and finally the Tawheed Book of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. The importance of this book is due to the fact that it was authored by the founder of modern Salafism and the most influential figure within the current Salafi trend, after Sheikh Ibn Taymiyah. The Book of Tawheed contains the sayings of the righteous Salaf and the true prophet Hadiths in order to highlight the “correct doctrine” and to show the monotheism in worship and God by criticizing what are considered the manifestations of polytheism and the inventive inputs in the Islamic faith.

Salafis 2.0?

Access to religious knowledge has been linked mainly to classical traditional schools as well as to the mosque. Recent years, however, have seen development in the level of access to religious knowledge due to to technological advancements that have facilitated access to resources. The Salafi trend has benefited from and adapted to the results of this technological development. The process of liberating the media from state dominance encouraged many investors to enter the media market. There has been an objective alliance between a group of “religious” businessmen and members of the Salafi stream so that a large network of Salafi satellite channels has been built in recent years. Some governments have worked before and after the Arab Spring to turn a blind eye to the activity of Salafi currents in the satellite channels. In some cases, these governments encouraged this trend, not considering the quietist Salafi trend as a security threat. In their view, Salafism can be used to balance out movements of political Islam, such as the Muslim Brotherhood.

As a result, a new group of Salafi preachers has emerged, benefitting from the media revolution in the Arab world and building a network of new customers, especially among women and young people.

- The Influential Religious Figure

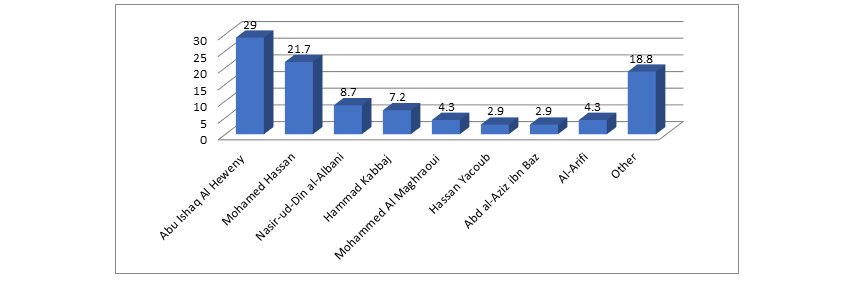

In response to an open question aimed at identifying influential religious figures, more than half of respondents said that the most influential religious figures in their lives were preachers and symbols from outside Morocco. The famous Egyptian sheikhs who preach on the Al-Nas satellite channel ranked among the most influential sheikhs for Moroccan Salafis. Sheikh Abu Ishaq Al Heweny took precedence with being the influential religious figure among 30 % of the total number of respondents, followed by Sheikh Mohammed Hassan (21 %), followed by Sheikh Al-Albani (Jordan) by 8 %. Sheikh Hammad Kabbaj is the first Moroccan Sheikh to be mentioned by respondents and occupies fourth place, mentioned by about 7 % of the respondents, followed Sheikh Mohammed Al Maghraoui with 4 % of the total respondents.

Chart 7: The most influential religious figure

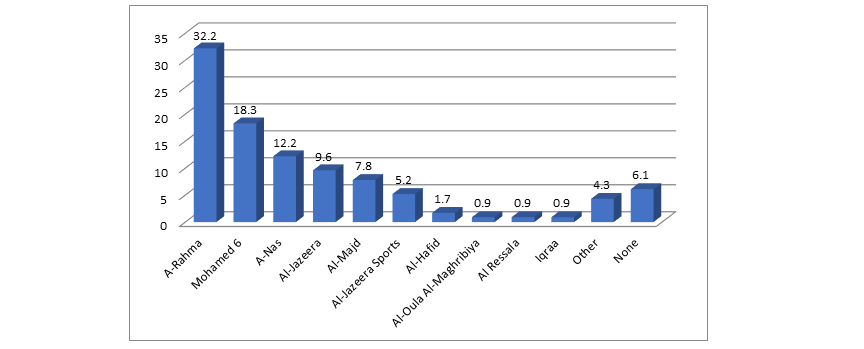

It seems that the presence of Egyptian Salafi sheikhs is mainly linked to the spread of Salafi satellite channels in recent years, most notably Al-Nas and A-Rahma channels. These two channels alone attracted about half of the respondents (A-Rahma, 34%), Al-Nas (13%). Assadissa, also known as Muhammad VI’s Channel of the Holy Quran, meanwhile, attracted about one fifth of respondents.

- Modern Technology

Assadissa is a Moroccan satellite channel funded by the Moroccan government. It is not affiliated with the Salafi movement, but it does broadcast various religious programs, focusing mainly on the model of Moroccan religiosity, which is based on the Maliki and Ash’ari doctrines, as well as Sunni Sufism. With the exception of the Maliki doctrine, Salafis do not share the ideological orientations of the state, especially with regard to the doctrine of Asharism and Sufism. Assadissa nonetheless occupies second place among Salafi viewers. This can be explained by the fact that Salafi respondents were eager to confirm the local dimension of their religion and distance themselves from allegations of allegiance to the Saudi Wahhabi school. It is also more likely that the Salafis selectively deal with this channel, listening to programs that intersect with their ideas, especially those that focus on faith.

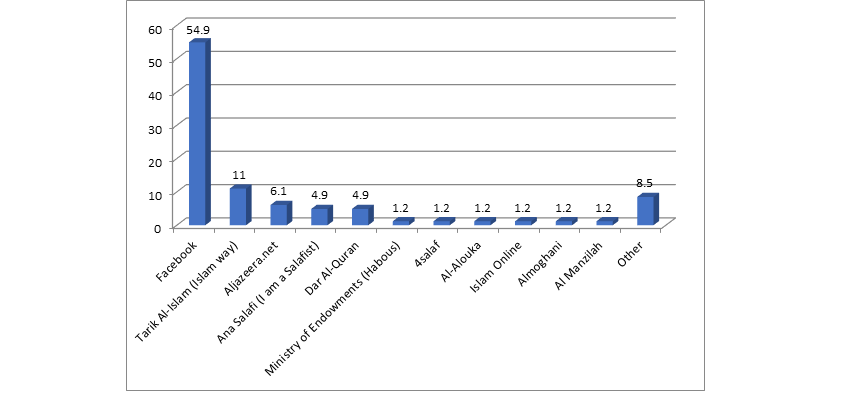

Online, Facebook leads as Salafis’ favored platform, with more than half of respondents indicating that they use Facebook as the first medium of communication, followed by the Tarik al-Islam website (Islam way), which is used by about one tenth of the respondents. The intensive use of Facebook indicates that Salafis use the Internet not only to access religious knowledge but also to communicate with each other.

Chart 8: Most Viewed Religious Channels

Chart 9: Most followed sites

The results of this field study go in tandem with the findings of a number of previous studies, including the 2007 daily Islam report, the national study on values conducted in 2006, and the second religious status report conducted in 2012.[11] The National Research Report on Values indicates close results with the results of our field research, in particular highlighting the existence of a great diversity of sources on religious knowledge and the introduction of new means of online communication. However, the report notes that the mosque remains at the top level of the source of religious knowledge for Moroccans, despite the competition of the modern means of communication of traditional religious institutions that have been put in a place of competition of these modern means of communication[12].

Table 2: Sources of Religious Information in Morocco (%)

| Females | Males | Source |

| 35.3 | 83.5 | Mosque |

| 55.4 | 44.6 | National TV Channels |

| 26.4 | 18.8 | Satellite Tv Channels |

| 30.4 | 4.5 | Family |

| 33.8 | 41.4 | Books |

| 2.3 | 3.0 | Internet |

Source: Synthesis Report on National Research on Values

The report of Islam daily confirms the same results of the fiftieth report, in which the mosque represents the first source of religious knowledge, followed by television, then friends and peers, and ultimately followed by reading in the fourth place. More than half of young respondents said that the current generation of young people had more religious knowledge than previous generations, and a third of respondents felt that their religious knowledge was greater than that of their parents, and that young people were less aware of it.[13]

Table 3: Sources of Religious Information According to Gender (%)

| Friends and Peers | Mosque | School | TV | Parents | Books | Source of Information |

| 24 | 40 | 3 | 29 | 7 | 18 | Men |

| 23 | 11 | 2 | 39 | 15 | 12 | Women |

Source: Daily Islam Report

Shari’a and Identity Issues

Salafis have special perceptions about society and relationships among its members. They consider religious belief to be the basic link between the various components of society, rather than citizenship or nationality. In the eyes of the Salafi, the creedal association has greater power than other social ties. Salafis therefore classify individuals and stigmatize them based on their proximity or distance from the Salafi standard. However, in comparing the results of our latest field study with previous studies on non-Salafis, we found that Moroccan Salafis’ attitudes are similar to non-Salafis in some issues while they are different in others.

- Attitudes Towards Society

In attempting to learn the Salafi attitude towards Moroccan society, we asked questions about the Salafis’ vision of society and whether the current reality is in line with their perception of the ideal society. We asked whether the implementation of Shari’a was one of the most salient issues with which Salafis are concerned. We asked our respoondents whether Sharia can be applied in Morocco both now and in the future. We then asked to describe the proportion of Moroccan society in harmony with the requirements of Shari’a. Finally, we asked about the comparative dimension with other countries that, according to the Salafis, ideally implement Sharia.

Regarding the main question on the attitudes of Salafis towards Moroccan society and whether, in their opinion, it is compatible with the religious authority, half of the respondents answered that Moroccan society is rife with heresy. About one-tenth of the respondents answered that it is a non-Islamic society in many aspects while about one-third of the respondents said that Moroccan society is a Muslim community based partly on the Quran and Sunnah. Only 2 % of the respondents consider Moroccan society to be entirely based on the Qur’an and Sunna. To investigate this question further, respondents were asked to give a number to determine the %age of Moroccans committed to the Quran and Sunnah, 10 being fully committed and 1 indicating no commitment . About 45 % answered that the Moroccans are not committed to the Quran and the Sunnah (rating Moroccan society somewhere between 1 and 3 on the scale), while nearly half of the respondents said that the Moroccan commitment was average (between 4 and 6). Less than 7 % of respondents believed that Moroccans were fully committed.

Chart 10: Attitude towards Moroccan society

Table 4: Percentage of Moroccans who apply the teachings of the Qur’an and Sunnah

| % | Frequency |

| 45,5 | Less than 3 |

| 47,5 | Between 4 and 6 |

| 7 | Above 7 |

| 100 | Total |

- Implementing Shari’a

The second sub-index concerns understanding the position of the Salafis on the implementation of Sharia. Four interrelated questions were raised regarding the possibility of its implementation under current circumstances. Respondents were also asked an open question regarding the state’s application of Islamic law.

With respect to the question pertaining to the implementation of Sharia law, half of the sample viewed the idea positively while the other half expressed doubts about its feasibility. The vast majority (97%) of respondents supported a gradual implementation of Shari’a and rejected the idea that implementing Shari’a in the present time was impossible because it was outdated.

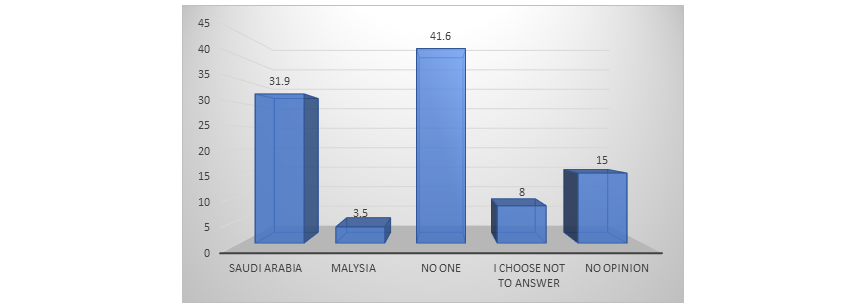

An open question was asked regarding countries that currently implement Islamic law. Surprisingly, 40% of respondents felt that no country in the world currently fully implements Shari’a. Nearly a quarter of the respondents had no answer to this question and 30 % responded that only Saudi Arabia implements the Shari’a fully. None of the respondents referred to Morocco as an Islamic state, although the Moroccan Constitution indicates that Islam is the official religion of the Kingdom and that legislative texts should not conflict with religion.

Chart 11: Attitude towards the implementation of Shari’a

Chart 12: Countries that implement Shari’a Today

To compare Salafi perceptions of Shari’a law with earlier studies, we refer to a Gallup study published in late 2006 entitled “Islam and Democracy”, which included about 10 Muslim-majority countries. The results came close to those of the research we have conducted about Salafis. Regarding the position of Islamic law in the legislation, 33 % of Moroccan respondents considered that Shari’a should be the sole source of legislation, 65 % considered it to be the primary source but not the only one, and only 2 % of the respondents felt that Shari’a should not be source of legislation.[14]

Table 5: Percentage of Islamic law in legislation (%)

| Do not know / refuse to answer | Sharia is not a source of legislation | Shari’a is an essential source of legislation, but not the only one | Shari’a must be the sole source of legislation | Country |

| 8 | 1 | 24 | 66 | Egypt |

| 15 | 4 | 21 | 60 | Pakistan |

| 5 | 1 | 39 | 54 | Jordan |

| 0 | 2 | 65 | 33 | Morocco |

| 11 | 57 | 23 | 9 | Turkey |

| 2 | 33 | 57 | 8 | Lebanon |

Source: The Gallup Organization

When asked what the role of theologians and religious scholars should be in drafting a state constitution, 16% of respondents said that they should have a direct role, 9% felt they should play an advisory role, and 73% felt that they should have an indirect role.[15] The following table shows the role that the religious scholar should play in drafting the constitution:

Table 6: The role of scholars in drafting the state constitution

| Unknown | Undirect role | Advisor | Direct role | Country |

| 2 | 50 | 9 | 39 | Jordan |

| 2 | 73 | 9 | 16 | Morocco |

| 4 | 72 | 8 | 16 | Turkey |

| 0 | 85 | 1 | 14 | Lebanon |

Source: The Gallup Organization

- Women’s dress

Regarding the question of women’s clothing and whether women have the right to choose their attire based on their own preferences, three-quarters of the respondents answered that the niqab is necessary for women. Furthermore, 85 % said that both niqab and hijab (face and hands) are equally important. Half of the respondents considered that wearing a headscarf was sufficient, while the vast majority opposed giving women the right dress as they see fit or the freedom to wear whatever they wanted.

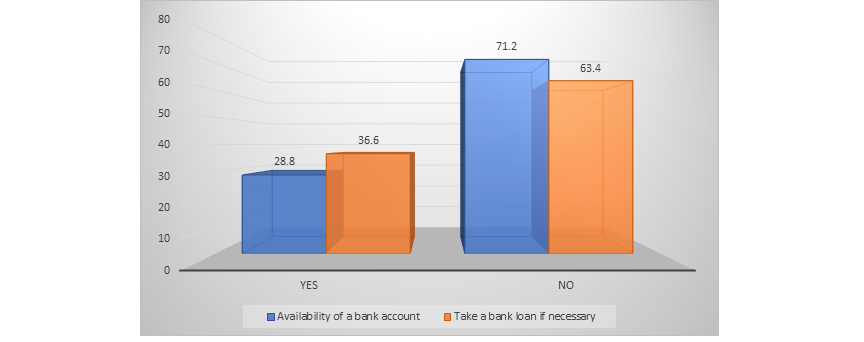

- Dealing with traditional banking institutions

The study also sought to identify the Salafi positions toward daily issues, especially dealing with modern institutions, like banks. Less than one-third of respondents have a bank account. An open question was asked as to why they had or did not have a bank account. Respondents’ answers show that the reason for the availability of the bank account is not due to purely religious reasons. Some people who have an account have considered it a necessity in daily life, especially students who live in places away from their families and receive remittances, while others consider that there is no reason to open a bank account because they only deal in cash.

We also attempted to identify whether Salafis are pragmatic about “riba” loans[16] if they were to be necessary. The following question was asked:

- In the event of a member of your family being in a critical health situation that requires a lot of money and the only remaining solution is borrowing from the bank, will you accept the loan? Justify your response.

In this regard, one-third of the respondents replied that they would, if obliged, obtain a riba-based loan from a bank because it falls under the principle of necessity. The remaining two-thirds of the respondents, however, said they would not take out a riba-based loan and would instead seek other alternatives.

Chart 13: Dealing with banking institutions

Table 7: Reasons for dealing with banks

| Frequency | Reasons | Order |

| 14 | Because I am an employee and I receive my salary through the bank | 1 |

| 6 | Bank transfers and deposits | 2 |

| 6 | Of necessity | 3 |

| 5 | Benefit from student scholarship | 4 |

| 3 | No reason | 5 |

| 1 | For commercial purposes | 6 |

| 1 | To avoid being robbed | 7 |

Table 8: Reasons for not dealing with banks

| Frequency | Reason | Order |

| 36 | No reason | 1 |

| 23 | Because of Riba | 2 |

| 12 | I have no income | 3 |

| 7 | Because it is Harram | 4 |

| 4 | I don’t need banks | 5 |

| 1 | To avoid suspicion | 6 |

| 1 | Because there are no Islamic banks in Morocco | 7 |

Table 9: Reasons for taking a loan from the bank in exceptional cases

| Frequency | Reason | Order |

| 31 | Necessities allow prohibitions / urgent need | 1 |

| 2 | No reason | 2 |

| 2 | It’s the only solution | 3 |

| 2 | Because I am in need of money | 4 |

| 1 | In need of committing several evils, we commit the least serious | 5 |

| 1 | prioritization | 6 |

Table 10: Reasons for refusing to take a loan from the bank in exceptional cases

| Frequency | Reason | Order |

| 28 | No reason | 1 |

| 19 | Because it is forbidden (Harram) | 2 |

| 9 | Because it is Riba (ribā) | 3 |

| 6 | Consult the scholars | 4 |

| 5 | There must be another solution | 5 |

| 4 | Bring confidence in Allah | 6 |

| 3 | It is a war against Allah | 7 |

Armed Violence

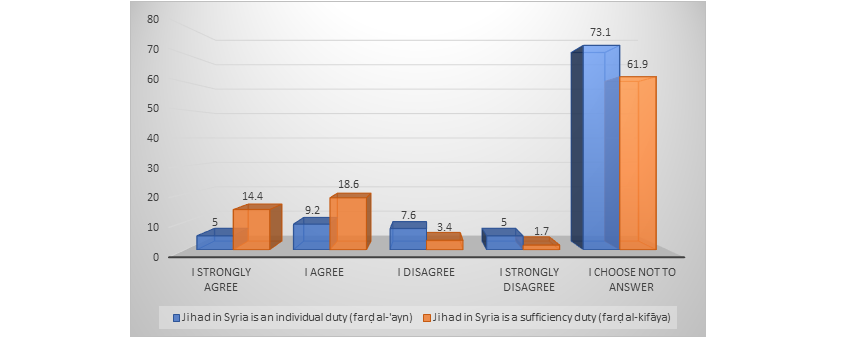

The question of Salafi perceptions and attitudes towards the issue of armed violence and support for armed insurgencies is among the most controversial. Notably, most respondents refused to answer the question about their position regarding the issue of jihad in Syria.

It should be noted that we completed the study in the latter half of 2013 and into early 2014. This corresponded with the ideological mobilization of the Syrian revolution and Salafis’ refusal to answer the question was striking. About two-thirds of the respondents refused to answer a question about whether they supported the Syrian revolution. The remaining third of the respondents agreed to answer but expressed discomfort with this type of question. Among them, 13 % of all respondents answered that jihad was an individual duty while a third considered it to be a collective duty. As for travel to Syria to fight, about 5 % replied that they were in agreement while a quarter of the respondents opposed it.

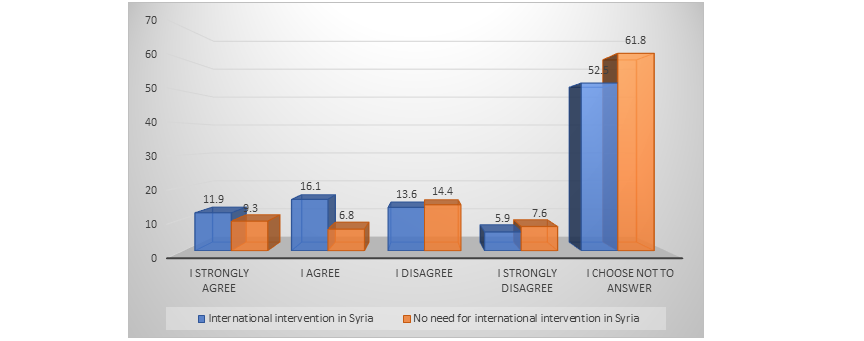

Chart 14: Jihad in Syria is a duty

Chart 15: Attitude towards external intervention in Syria

Chart 16: Attitude towards traveling to Syria to fight and armed revolution

Political Participation

Salafis gained momentum and achieved significant presence in the public sphere after the wave of popular protests across the Arab world in 2011. The February 20th movement presented Moroccan Salafis with the opportunity to break out of the isolation imposed on them after the 2003 Casablanca bombings and make some political gains. Moroccan Salafis actively participated in the February 20th protests.

Moroccan authorities reacted with flexibility to Salafi protests and attempted to dispel some of their discontent through a number of excessive measures as part of a settlement process that sought to rearrange the political scene and adapt to the context imposed by the street movement. Less than two months after the popular protests broke out, the Moroccan monarch pardoned a group of Salafi sheikhs, including Sheikh Mohamed al-Fayzazi. In early 2012, a second batch of Salafi detainees was released. In April 2011, the authorities permitted Sheikh Mohammed al-Maghraoui to return from his voluntary exile in Saudi Arabia since 2008 after issuing a fatwa on the marriage of minors. Maghraoui’s fatwa caused controversy at the time, leading the Ministry of Interior to issue a decision to close houses of the Qur’an that were close to the Call to the Qur’an and Sunnah Association. The Ministry of the Interior also reopened those closed the Qur’anic schools as part of the arrangements designed to dampen the anger of the quietist Salafis.

The political openness of 2011 led to the politicization of part of the preaching Salafi movement after decades of boycott. During the past six years, the preaching Salafi current has taken a pragmatic approach to dealing with political changes, manifested in the call for a vote on the constitution, running in elections, or supporting various secular and Islamic parties.[17]

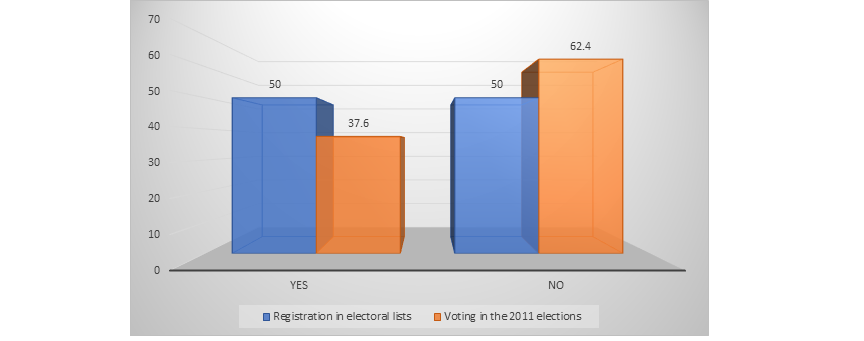

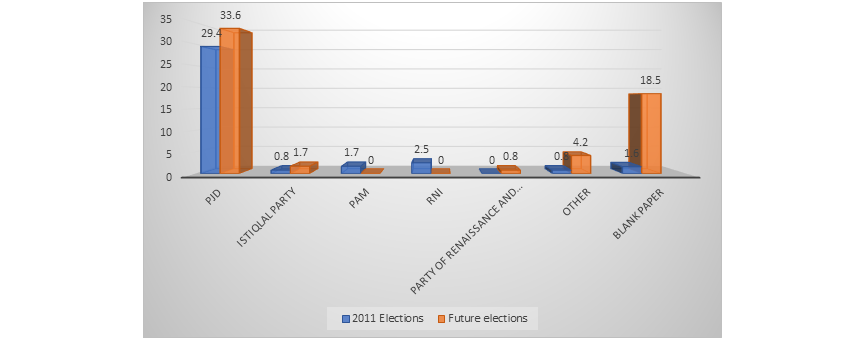

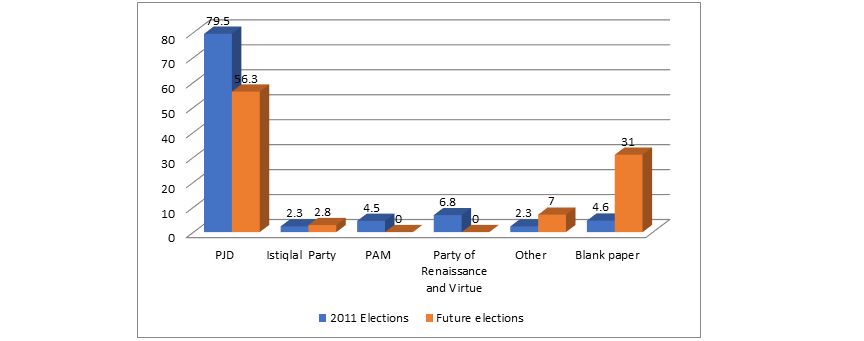

Within this context, an axis was devoted to Salafi behavior and attitudes towards electoral participation, and direct questions were asked about their behavior during previous elections and their intention to vote in upcoming contests. The findings show that Salafi attitudes differ from the traditional perception of their departure from the political sphere and their indifference to the electoral process. According to the results of the research, about half of the surveyed Salafis are registered in electoral lists. However, only 37% had participated in the legislative elections of November 2011, while nearly two-thirds did not participate at all.

Concerning the parties Salafis voted for, the Justice and Development Party came first with 79 % of the total number of votes in the 2011 elections. The National Rally of Independents came second with about 7 % followed by the Authenticity and Modernity Party with about 5 %. As for the upcoming elections, Salafis have lost trust in political parties. The Justice and Development Party saw a drop in Salafi support from 79 % in 2011 to 56 % in 2014, among those who expressed a desire to vote in the next elections. Those intending to submit a blank ballot increased to about 31%.

Chart 17: Registration in electoral lists

Chart 18: Voting in the 2011 elections and future elections[18]

Chart 19: Voting in the 2011 elections and future elections[19]

As political leaders, it appears that Salafis are largely unimpressed. An open question asking respondents to name the most influential political figure in their lives saw only 33 of the 118 respondents answer the question (or about 28%). A full 72 % of the respondents were unable to name a single influential political figure. Of the 28% who responded, 40% named Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, 21% named Moroccan Prime Minister Abdellah Benkirane, and 12% named Egyptian politician Hazem Salah Abu Ismail.

Responses to this question highlight the admiration for the Turkish experience, its Justice and Development Party, and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan. This admiration is also at least in part a result of a number of respondents’ visits to Turkey in the framework of cultural or tourist activities and their meetings with representatives of Turkish civil society. It is interesting that Salafis regard Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as one of the most influential personalities in the region and that they see him as an example for gradual and balanced reform that would fulfill the public’s worldly needs while preserving identity.

Salafis’ position towards this issue is no different from that of Arab public opinion. A number of opinion polls indicate that Erdogan is, to most Arabs, the most influential political figure in the world. The Brookings Institute noted in 2011 that Turkey is the biggest winner in the Arab Spring. Of the five countries surveyed in 2011, they found that Turkey played a “very constructive” role in Arab events. Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is the most impressive figure among the world’s leaders and those who envision a new president want this new president to be similar to Erdogan.[20] Seventy-eight % of Moroccans admired Erdogan’s policies and 82 % said that they felt that Turkey had contributed to peace and stability in the Arab world.[21]

Chart 20: The Influential Political Figure

Salafis and the “Other”

- Friendship and coexistence with the other

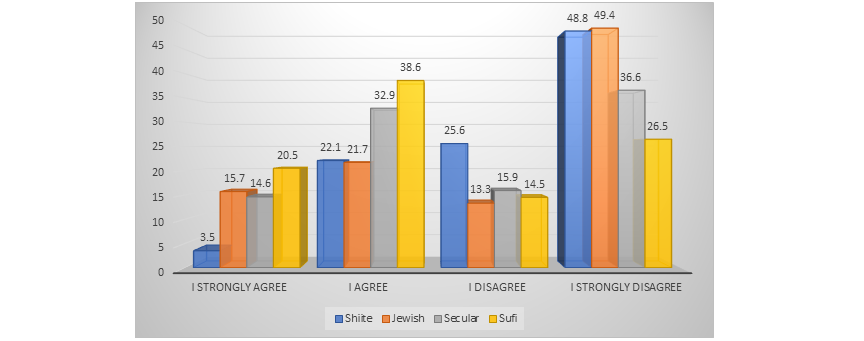

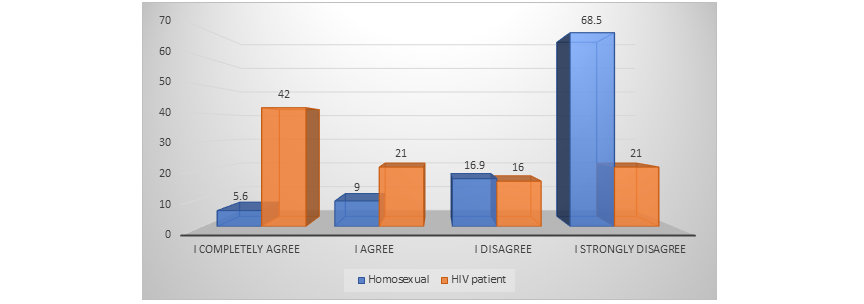

This set of questions aimed to assess respondents’ openness to friendship with different groups, including Shiites, Jews, people with sexually transmitted diseases, homosexuals, Sufis, and secularists. They were categorized from most open to friendship to the least open. Results indicate that Salafis are most hostile to homosexuals followed immediately by Shiites, then Jews, secularists, and Sufis. Salafis are most open to friendship with HIV patients. The survey found that 85 % of respondents refused to connect with a gay person and about three-quarters of respondents refuse friendship with a Shiite. Two-thirds of respondents refuse friendship with a Jew, half refuse friendship with a secularist, and 40 % refuse friendship with Sufis or a person with HIV/ AIDS.

Chart 21: Attitude towards friendship with (1)

Chart 22: Attitude towards friendship with (2)

- States that threaten the region

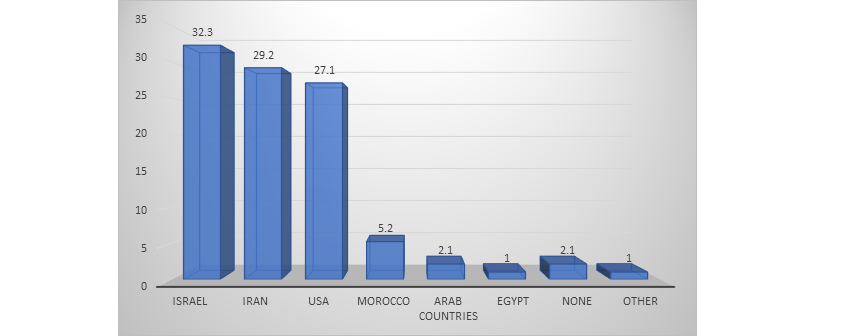

The same anti-Jewish and anti-Shiite sentiment is found in perceptions regarding international relations. Through the open question posed to respondents about the state that poses the greatest threat to the Muslim world, Israel, Iran, and the United States topped the list of countries. These countries accounted for about 90 % of the respondents’ answers, while 5 % of respondents referred to the West in general as the main threat to the Muslim world, and only 3 % of respondents referenced other countries Arab or otherwise.

Chart 23: Countries that threaten the Muslim world more

In a section devoted to the Salafis’ position on evangelization, a question related to the position from missionary activities was asked. Ninety-seven % of respondents objected to proselytizing activities (24 % disagreed, 73 strongly disagreed), while only 3 % agreed.

Chart 24: Christians can spread their religion

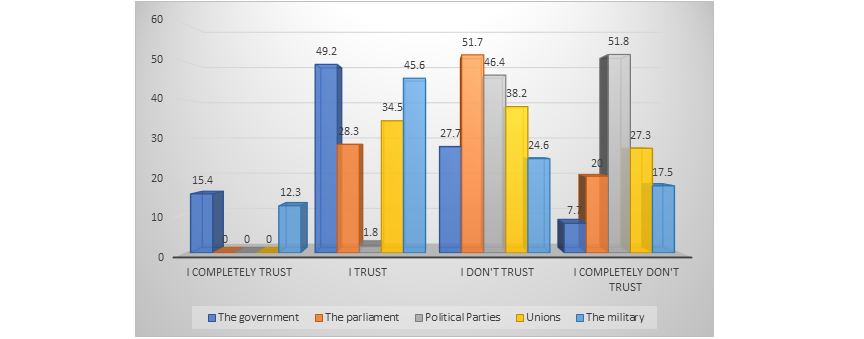

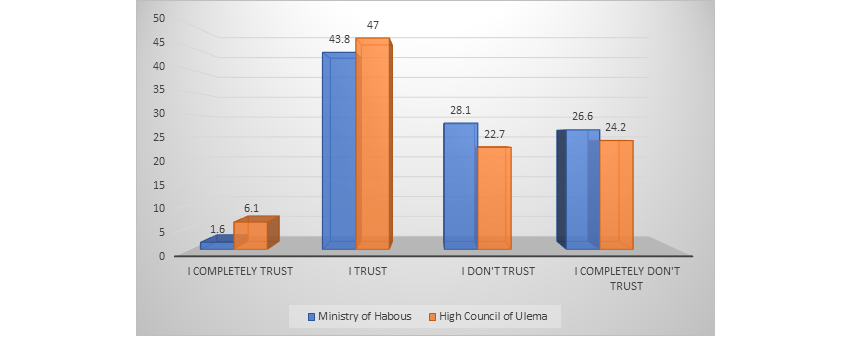

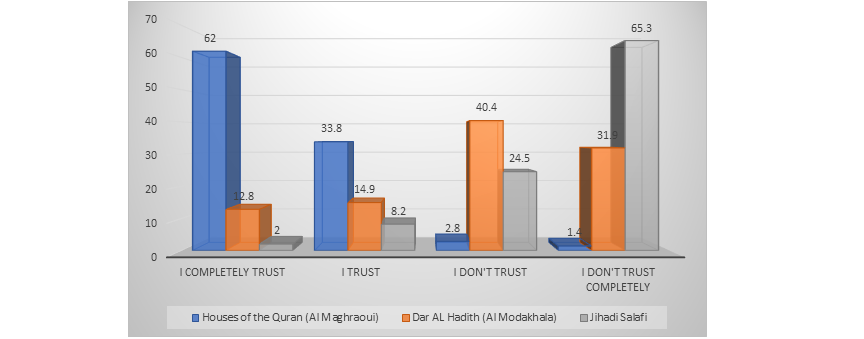

Trust in Institutions

The value of trust is one of the elements that helps to understand Salafi positions towards public life. Salafis’ refusal to participate in politics has weakened their trust in official and partisan institutions. More than twenty indicators have been monitored to measure Salafis’ trust in institutions. The institutions that have been put in question included governmental and non-governmental institutions and official and state-independent religious institutions.

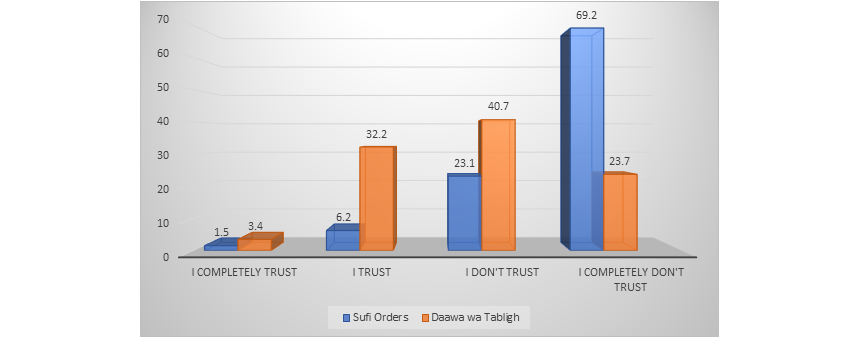

The Qur’anic schools belonging to Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdul Rahman al-Maghraoui come at the top of the institutions that the Salafis trust with 96% of valid responses. The houses are followed by the Government and the Justice and Development Party (PJD) with 65 % and the institution of the military (58 %). While the official religious institutions (the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs, the Supreme Scientific Council and the local scientific councils) enjoy the trust of half of the respondents. The unification and reform movement gained 40 % trust ratio while trade unions, the independent press and the Tablighi group[22] received the trust of one-third of the respondents. Political parties came in at the bottom rung as the institution, enjoying the lowest level of confidence (2%), followed by the United Nations, the Sufi Zawaya, public TV channels, Jihadi currents and Justice and Charity.

Chart 25: Trust in Institutions

Chart 26: Trust in government institutions

Chart 27: Trust in the press

Chart 28: Trust in official religious institutions

Chart 29: Trust in non-official religious actors (1)

Chart 30: Trust in non-official religious actors (2)

Chart 31: Trust in non-official religious actors (3)

Conclusion

This study attempts to shed light on Salafi perceptions of themselves and the environment surrounding them by standing at the sources of knowledge they rely on to build their intellectual perceptions, as well as the way they look at a number of issues related to everyday life.

In general, the study emphasizes a number of abstracts:

- The Salafis’ keen interest in traditional religious knowledge, which can be attributed to the prominent interest in the books of Islamic heritage.

- Yet, Salafis appear to be open to modern technology. The results of this study have shown this interest in modern technology as one of the Salafis’ sources used in building their perceptions.

- Salafis appear to be intolerant to the position of women’s dress and have expressed closed positions regarding coexistence with others, especially friendship with Shiites, secularists and homosexuality.

- In general, the quietist Salafi current rejects armed violence, with most respondents refusing to justify travel to fight in Syria.

- Salafis show some flexibility in terms of political participation. While the activists of this current backed the Justice and Development Party in the 2011 elections, it can be seen that the Salafis have reconsidered their position by abstaining from voting in future elections.

- While Salafis show trust in the role of the associations of the houses of the Qur’an, their level of trust in formal political and religious institutions seems weak.

Notes

[1] In 2014 the International Center for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence at King’s college published the results of a quantitative study on European fighters in Syria, based on a database made up of personal social media pages from about 190 European fightersin Syria and elsewhere. See:

Joseph A. Carter, Shiraz Maher, Peter R. Neumann, “Greenbirds: Measuring Importance and Influence in Syrian Foreign Fighter Networks“, ICRS, 2014.

[2] Gary LaFree, Kathleen Smarick, Shira Fishman, “Community-level Indicators of Radicalization: A Data and Measurement Workshop”. START, 2009. http://www.start.umd.edu/research-projects/community-level-indicators-radicalization-data-and-measurement-workshop

[3] There are several obstacles in surveying extremism in society. The first obstacle is related to defining the concept of extremism itself, as well as to finding indicators for measurement. What some consider extreme is considered by others as a criterion or principle. The second dilemma relates to the difficulty of finding objective quantitative indicators that can be measured within different cultural formations.

[4] Mohammed Abu Rumman, I AM A SALAFI: A Study of the Actual and Imagined Identities of Salafis, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Amman, 2014.

[5] Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Maghraoui is one of the most prominent symbols of the traditional Salafi trend in Morocco. Although the headquarters of his association are located in the city of Marrakesh, it succeeded in building a wide network of Salafi associations throughout the country. The Maghraoui trend is characterized by its rejection of political participation and a focus on sponsorship and ideological construction, while Sheikh Hammad Kabbaj represents another example of the traditional Salafi trend. Despite their participation in the Salafi creed, Sheikh Hammad Kabbaj is characterized by a greater dose of politicization and a desire for political participation.

[6] Regardless of the results of this study, quantitative analysis helps answer the question “how?” Not “why?” There is therefore a need to deepen the results of this study at the qualitative level, by explaining and giving meaning to the answers, which a future study of the author will try to do. In addition, it is important that the study also includes a detailed and comprehensive comparison of the perceptions of the general community (non-Salafis) on the same issues to come up with conclusions that help to compare the Salafi and others. We have tried to do this using what is available in open studies.

[7] It should be noted that we tried to involve females in this study but the nature of the research makes it impossible to do this, so the quantitative field study was completed with males only.

[8] Roel Meijer. “Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement.” (2009): 75.

[9] The list includes more than forty books, but the it was limited to the ten most read books by the research sample.

[10] The book of Muslim took him about 15 years to gather and classify it. The book is a collection of more than three thousand Hadith, which includes the Prophet’s authentic Hadiths in matters of jurisprudence and doctrine and others.

[11] Mustapha El Khalfi et al., Religious Status Report in Morocco 2007-2008, Moroccan Center for Contemporary Studies and Research, First Edition, Rabat. 2009

[12] Hassan Rashik et al., Synthesis Report on National Research on Values: 50 Years of Human Development. 2006

[13] Mohamed Tozy et al., ’islam Au Quotidien, Enquête sur les Valeurs et les Pratiques Religieuses au Maroc, [Islam in Everyday Life: Survey of Values and Religious Practices in Morocco], Editions Prologues. 2007

[14] Dalia Mogahed, Islam and Democracy, The Gallup Organization, 2006.

[15] Dalia Mogahed, Islam and Democracy, Op. Cit.

[16] Riba (usury) is a concept used in the context of Islamic jurisprudence to refer to the massive/unfair gain made in business. The Sharia Law forbade it because it is thought to be exploitative. The modern banking system is thought to be Riba-based, because it is interest-based.

[17] Mohammed Masbah, Between Preaching and Activism: How Politics Divided Morocco’s Salafis, Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, May 2018. Link: https://mipa.institute/5615

[18] Of the total number of respondents

[19] Age of those who voted in the 2011 elections

[20] Arab Public Opinion Poll 2011, Brookings Institution, November 2011. Link: http://www.brookings.edu/en/research/reports/2011/11/21-arab-public-opinion-telhami

[21] Arab Attitudes, 2011, Zogby International

[22] Tablighi Jamaat (or group) is a apolitical Sunni Islamic missionary movement that focuses on urging Muslims to return to primary Sunni Islam and particularly in matters of ritual, dress, and personal behavior. They are widespread mainly in the South Asia but have large network all over the world.

References:

- Arab Public Opinion Poll 2011, Brookings Institution, November 2011. Link (http://www.brookings.edu/ar/research/reports/2011/11/21-arab-public-opinion-telhami(

- Mohamed Tozy et al., ’islam Au Quotidien, Enquête sur les Valeurs et les Pratiques Religieuses au Maroc, [Islam in Everyday Life: Survey of Values and Religious Practices in Morocco], Editions Prologues. 2007

- Mustapha El Khalfi et al., Religious Status Report in Morocco 2007-2008, Moroccan Center for Contemporary Studies and Research, First Edition, Rabat. 2009

- Hassan Rashik et al., Synthesis Report on National Research on Values: 50 Years of Human Development. 2006

- Roel Meijer. “Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement.” (2009): 75.

- Mohammed Masbah, Between Preaching and Activism: How Politics Divided Morocco’s Salafis, Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, May 2018. Link: https://mipa.institute/5615

- Arab Attitudes, Zogby International, 2011.

- Dalia Mogahed, Islam and Democracy, The Gallup Organization, 2006.

- Gary LaFree, Kathleen Smarick, Shira Fishman, “Community-level Indicators of Radicalization: A Data and Measurement Workshop”. START, 2009. http://www.start.umd.edu/research-projects/community-level-indicators-radicalization-data-and-measurement-workshop

- Joseph A. Carter, Shiraz Maher, Peter R. Neumann, “Greenbirds: Measuring Importance and Influence in Syrian Foreign Fighter Networks”, ICRS, 2014.

- Muhammad Abu Rumman, I am Salafi: Research on the Realistic and Imaginary Identity of Salafis, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Amman, 2014.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Mohammed Masbah

Mohammed Masbah is the Founder and President of the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA). He is a political sociologist whose work centers on public policy, democratization and political Islam, with a focus on North Africa. Dr Masbah is an Associate Fellow at Chatham House in London and adjunct professor at Mohammed V University. He was previously a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center, and a fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP) in Berlin. Dr Masbah obtained his PhD in Sociology from Mohammad V University in Rabat. His dissertation examined the processes of radicalization and deradicalization of Moroccan Salafis since Casablanca bombings in 2003. His recent publications include: Moroccan Jihadists: Local and Global Dimensions, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 2021. Trust in Institutions Index 2020, Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, 2020. Rise and Endurance: Moderate Islamists and Electoral Politics in the Aftermath of the ‘Moroccan Spring’” in Islamists and the Politics of the Arab Uprisings: Governance, Pluralisation and Contention (Edinburgh University Press, 2018) Contact the author: m.masbah@mipa.institute