[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Social protests in Morocco may shift to political claims due to the socio-economic exclusion of some regions

Executive summary

Since late 2016, protests in Morocco have increasingly shifted, from being an urban phenomenon, toward rural and semi-urban areas. Yet, while the demands of protesters focus on improving basic services, such as health care and electricity, the escalation in intensity and the range of protests might have led to a contagion effect thereby increasing uncertainty among protesters. A new trend of these protests is their determination to challenge the repressive measures of authorities despite the high cost that this entails.

In fact, the ongoing street protests in the rural margins of Morocco are signs of distrust between the population and the elected institutions, which have become increasingly alienated from citizens. Hence, rendering the same citizens that elected them skeptical about the effectiveness of these institutions to improve their economic situation. These protests are also a result of the shared feelings of exclusion among Morocco’s marginalized regions, who arecalled “the deep Morocco” in local media. These regions have developed a collective identity, giving birth to the revival of territorial solidarity based on kinship and tribal ties, which has resulted, in some cases, in a clan-based dimension to the protest action, most probably leading the shift of demands from social to political.

Introduction

By the end of 2017, the province of Jerada, located in the far east of Morocco, witnessed a wave of popular protests against the tragic death of brothers Hussein and Jadouane, who died while extracting coal from a deserted mine using primitive instruments. Months earlier, the Zagora region, in southeastern Morocco, witnessed a wave of protests due to water scarcity and rareness of drinking water wells due to the depletion of aquifer by the owners of large watermelons farms.. Both provinces are amongst the poorest areas in the country.

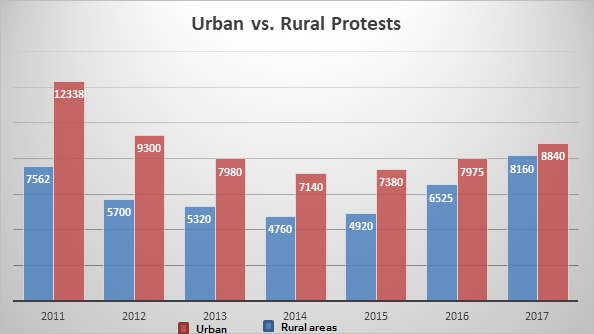

The protests of Jarada, Zagora and other regions are examples of a new wave of protests in Morocco’s rural margins in recent years. Unlike the protests of February 20, 2011,which were dominated by the visibility of urban lower middle classes, the new wave of protests of rural areas is a shift in the nature of protest movements in Morocco that moved from being mainly urban and progressed leaking into Morocco’s deep margins, which have been largely isolated from the dynamics of social mobility for a long time. Out of the eleven thousand protests counted in 2017, half of them were in the rural areas[1]. This rate is higher compared to previous years, when the number of protests in rural areas was only 40 percent2. The number of urban dwellers accounts for about two thirds of Morocco’s population, meaning that the number of protests in rural areas in Morocco remains high.

Although most of these protests focus on grievances related to social services, especially provisions of health care, electricity supply and drinking water, the possibility of a snowball effect might exist in case the government opts only for a security oriented approach instead of tackling these grievances seriously.

This paper argues that Morocco will face a new wave of protests in the coming years due to high expectations of citizens and the inability of successive governments to meet these expectations in an acceptable manner. This paper also argues that the shift of protests from urban to rural areas is linked to the decline of notables and local authorities who function as local mediators. In the past, they have been instrumental and effective in mediating grievances by containing them in an early stage. The social transformations have led to the decline of these mediators and to increasing protesting awareness in isolated areas, making it more difficult than ever to pre-emptively control protests and absorb the citizens’ anger.

Furthermore, this new wave of protests indicates the failure of the successive government’s development projects over the past two decades and the unachieved promises to improve the socio-economic situation and to develop the poor and marginalized areas3. The high rates of poverty and vulnerability in these areas also indicate the failure of public policies directed towards these marginalized areas. Hence, the development policies of the governments are questioned both in terms of effectiveness and in terms of beneficiaries.

Protests Contagion

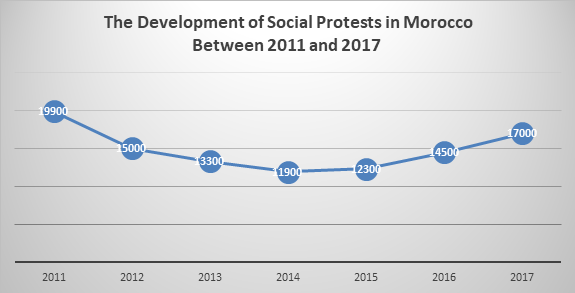

After the Abdelilah Benkirane government was appointed in 2012, the pace of the protests relatively declined. This might be linked to the hopes of citizens to improve the situation, especially in the early two years of the government. However, the frequency of protests rose again in 2014 and in 2016 in the Rif region following the wave of protests in the region after the gruesome death of fishmonger Mohssin Fikri4.

Source: compiled by author[2]

Source: compiled by author[3]

Although its impact was not direct, the ‘Hirak’ (protests) in the Rif region, which erupted since October 2016, was contagious inspiring other marginalized areas to protest and gave them an important boost. Despite the authorities’ repression of the protests in the Rif, residents of small villages and towns didn’t hesitate to go out on the street to raise their social demands against local officials and bureaucrats.

There seems to be a learning process between margin protests and the Hirak. This is supported by the adoption of continuous demonstrations in order to pressure authorities. Unlike the February 20 movement, which depended on seasonal protests, both the Hirak and the margins’ movement adopted continuous protest activity. This was in addition to the use of social media used by the protesters. These techniques have been invested in heavily by the Rif protests and have proved effective. The learning process was also clear in the fact that the protests of the margins focused primarily on social demands, particularly the provision of basic services and needs of economic alternatives. It also focused on national unity, through the display of the national flag, which differed from Hirak in the Rif that was run, whether intentionally or un-intentionally, by cultural and political demands, although they both share the same social grievances.

Style of protesting

In general, the demands of the margins’ protests focused mainly on the classic demands for accessibility of basic services5. However, as mentioned above, the year 2017 also marked the emergence of protests related to climate change and the environment. A number of small villages and marginalized areas have protested against the high costs of drinking water bills, water sanitation, water scarcity and the lack of access to drinking water in areas which increasingly suffer from the drought of some of the wells on which they relied.

According to official data, the summer of 2017 alone witnessed the protest of more than 37 rural centers. The State Secretary in charge of water, Charafat Afilal, admitted that two thirds of the areas where the protests took place knew scarcity of waters. Zagora rallies are the most prominent illustration of the new wave of environmental protests that demand solving water scarcity caused by the depletion of aquifer by watermelon farms. This led to a violent clash between the protesters and the authorities, resulting in many arrests and trials6.

The nature of these social demands, however, might eventually turn into political ones, mainly because of the failure to find mid to long term solutions to meet the basic demands of the population. This might happen by calling for the removal of local political and administrative officials, as has been the case in some villages and cities in 2017 when protesters called to sack the governor and other local officials.

Interestingly, the new wave of protests is using new strategies and techniques to attract the attention of the authorities and the public opinion. One new strategy is “walking protests”, which means expressing their anger through long distances marches, with high risk sometimes. In some cases, citizens walked more than 70 km to arrive to the office of the governor. Seemingly, the reason behind these long-distance “walking protests” is to demonstrate the extent of suffering, and to attract the attention of officials in an effort to talk to them7.

In addition, activists have invested heavily in social mediain order to communicate demands and expectations to officials in Rabat to highlight and showcase the extent of the suffering of these groups and the absence of basic services. Obviously, since 2011, Facebook has become one of the main channels to express grievances used extensively by protest movements.

As for the groups taking part in these protests, it is observed that in addition to youth, children and women have also been involved in protest marches, often on foot. Villagers have to travel long distances in order to communicate their demands to local officials, both in the center of the provinces or in the territorial communities in which they live. This indicates how much these marginalized groups are insisting on achieving their demands.

Interpretation of Margins’ Protests

To understand the shift of protest towards the margins, there are two key elements that help explain this development:

The firt is linked to government policies and its failure to implement comprehensive local development projects, mainly the slow-paced response to the needs and expectations of a large segment of citizens that caused social disparities to grow between villages and cities. Statistics of the High Commissioner for Planning on the poverty map indicates that by the end of 2017, more than four million impoverished Moroccans are mainly concentrated in specific rural regions. These areas often witness protests. Despite the relative decline in multidimensional poverty, this decline was limited to only 2% of cities, while the percentage was more than 17.7% in rural areas. This means that more than 85% of Morocco’s poor people live in rural areas8.

Moreover, the gap between the regions is still large, especially with respect to the provision of basic services such as electricity coverage, waste water treatment, drinking water, employment, health, education and administration services. According to official statistics, Casablanca and Rabat alone produce about half of Morocco’s GDP9, five others, Tangier-Al Hoceima, Meknes-Fez, Marrakech, and Beni Mellal-Khenifra, produce 40% of the GDP, while the oriental region, Daraa-Tafilalat, and southern regions produce 10% of GDP. These regional inequalities are also one of the reasons why inhabitants of the “deep Morocco” are protesting10.

The second element vital to the understanding of the dynamics of protests in marginalized areas is the emergence of individuality, or theindividual’s role within the group. The shared feeling of marginalization created a collective identity among the local population, thanks to the emergence of a new generation of an educated middle class who had completed their university studies and came back home with a social capital that enabled them to mobilize the protestors. Those people profited from horizontal social mobility but not a vertical one, meaning that they benefited from their education but did not reflect on their economic situation. This new middle class was comprised of teachers, unionists, unemployed educated youth and activists who worked together to organize local networks to lead the protest process.

In fact, social mobilization has been growing in rural areas, and in some smaller cities like Bouarfa, Al Hoceima, Zagora, Sefrou, Tiznit, Afni, Zayou, Taza, Tata, Ait Bouayach, and Jarada, thanks to the role played by these new social actors. The role of local civil society actors, hence, is no longer limited to civil action, but also to the organization of protests and advocacy in order to achieve some gains for the local community. It should be noted here that this new agency helped to create political awareness within the inhabitants of the rural areas, which helped reconfigure the concept of dignity in relation to the feeling of oppression and regional frustration11.

As mentioned earlier, the shrinking of local mediation channels has led to a vacuum between citizens and the state. This has unintentionally produced a shared collective identity among the local population, which feels that their marginalization is linked to failed public policies. These groups, which are united by the same demands, are now carrying out resistance strategies that are expressed not only through ongoing protests, but also through daily practices in public space in a way that expresses their rejection of authority. One such example is boycotting paying the electricity bills.

The failure of these social mediators is strikingly reflected in the declining role of classical trade union organizations and political parties in leading political activism. In the past, these institutions had a role in mobilizing protestors, whereas today they seem to be marginalized. This underlines the weak mechanisms of social mediation and the vulnerability of the elected representative institutions, and their inability to accommodate the demands and social expectations of citizens12. Local notables also lost much influence. For a long time, they played the role of the firefighter to limit these protests and nip them in the bud. The legitimacy of traditional mediators has worn off due to growing protesting awareness based on the idea of marginalization, social exclusion, ‘territorial oppression’and new approaches in social protests in rural areas and small cities of Morocco, based on traditional solidarity and synergy ties13. This has been observed both in the protest movement in Al Hoceima and in the recent protest movement in Zagora and Jarada. Despite the attempts of mediation by local notables to cool off the protests, the protesters continued their face to face struggle with the police.

Conclusion

Protest movements are no longer confined to the urban areas. The demands that have grown are the result of the feeling of territorial exclusion by the population of some regions and the marginalization of their local communities. The failure of the government and local authorities to respond to basic social demands of marginalized areas will lead to a growing echo of protests in the “deep Morocco” as a major form of communicating social injustice.

The feeling of marginalization also generated a common identity based on territorial solidarity between the people of the village or the tribe, and fueled by ties of kinship, belonging, and by the suffering shared by the inhabitants of the region. This would turn the protesting action into a quiet creeping force that shall give protests in Morocco new momentum byby challenging authorities and thereby forcing a change on the ground. This may be difficult to tackle in the future, or be justified in terms of the security-oriented approach. The issue is not related to movements with specific leaders, nor organized ideological identities easy to control, but related to protest movements involving thousands of angry people.

Hence, the authorities should work to find long-term social and economic solutions to achieve comprehensive and sustainable development in the regions by increasing the efficiency management of local institutions.

In the long term, further implementation of the project of regionalization, mainly the creation of a solidarity fund between regions, could play a role in reducing disparities. However, in the short term, authorities should adopt a flexible approach to dealing with the protests with open and frank dialogue with the citizens to restore their trust in the institutions.

Notes

1 Abdellatif Baraka, “Eleven thousand protest in Morocco every year … phenomenon between the right and the law”, Hibapress website, June 2017 http://www.hibapress.com/details-109431.html, See also: Khalfi: “Al Hoceima witnessed 700 Protest.. and the security interventions are limited” ,Alyaoum24, June 24 http://www.alyaoum24.com/887604.html

2 Abderrahman Rachik, “Protest Movements in Morocco from Rebellion to Demonstration”, Publications of Morocco Alternatives Forum, May 2014, p. 41.

3 “Pauvreté et prospérité partagée au Maroc du troisième millénaire, 2001-2014“, HCP,https://www.hcp.ma/Pauvrete-et-prosperite-partagee-au-Maroc-du-troisieme-millenaire-2001-2014_a2055.html

4 ALkhalfi: “Al Hoceima witnessed 700 Protest”, Ibid.

5 Said Bennis, Hespress, November 2017, https://www.hespress.com/writers/372226.html

6 Shaimaa Bakhssass, “The thirst protests”, Ultrasoft siteweb, https://www.ultrasawt.com

7 Said Bennis, Ibid.

8 Pauvreté et prospérité partagée au Maroc du troisième millénaire, 2001-2014 : https://www.hcp.ma/Pauvrete-et-prosperite-partagee-au-Maroc-du-troisieme-millenaire-2001-2014_a2055.html

9 Medias24, 48% du PIB national réalisé dans deux régions, septembre 2016 : https://www.medias24.com/MAROC/ECONOMIE/ECONOMIE/166834-48-du-PIB-national-realise-dans-deux-regions.html

10 Fattouma Naimi, Morocco needs 24 years to reduce social and rural disparities, Ahdath Anfo, http://ahdath.info/230343

11Said Bennis, Ibid.

12 Fattouma Naimi, Ibid.

13Abderrahman Rachik, Ibid.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]