[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Morocco’s strategy to battle the pandemic seems to be working thus far, but its healthcare system suffers from longstanding problems. Can the government glean lessons from this pandemic to substantively tackle health care reform?

Download article

Introduction

In Morocco, the response to COVID-19 reveals a paradox. While there is a surprising amount of state capacity to mobilize resources and combat the spread of the virus, at least for the short term,[1]the country’s healthcare system suffers from chronic weaknesses. The public is mistrustful of the health care sector, and most Moroccans perceive health care services in the country as low-quality.

The state’s ability to enforce an aggressive lockdown was significant. It mobilized security forces, public health resources, and financial support to mitigate the impact of the virus in the short term. The state of public health emergency has been extended until May 20, and, like many countries, discussions about easing lockdown measures have begun. According to MIPA’s recent survey, most citizens were satisfied with the government’s response to the pandemic and a majority even expressed trust in the government.[2]

These short-term successes are impressive. However, like most other nations, Morocco has been forced to confront serious problems in its health care sector that stem from acute inequalities in access to high-quality health care: a quality gap exists between the private and public health systems; regional disparities privilege urban communities over rural ones. Furthermore, a majority of the population does not have health insurance. These factors help explain the low level of trust in the public health system. As a MIPA survey recently showed, Moroccans have a negative perception of their health care system, and they do not trust its ability to cope with the pandemic.[3]These survey results reveal people’s concern about the quality of health care, as well as the underlying structural inequalities plaguing the health care system.

To make its way through this crisis, Moroccan society is relying on a highly centralized political system that can indeed mobilize resources quickly when confronted with crisis. Yet this state capacity should not overshadow the problems inherent in Morocco’s health care system. Rather, lessons should be gleaned from this crisis to jumpstart another significant health care reform process. To address the question of a new reform initiative, this paper will layout the most significant reforms efforts to date, as well as the layers of inequality in the health care system. It will conclude with some thoughts on Morocco, post-COVID, and some ideas on strategic priorities for Morocco’s healthcare system.

Improvements and Reform Efforts

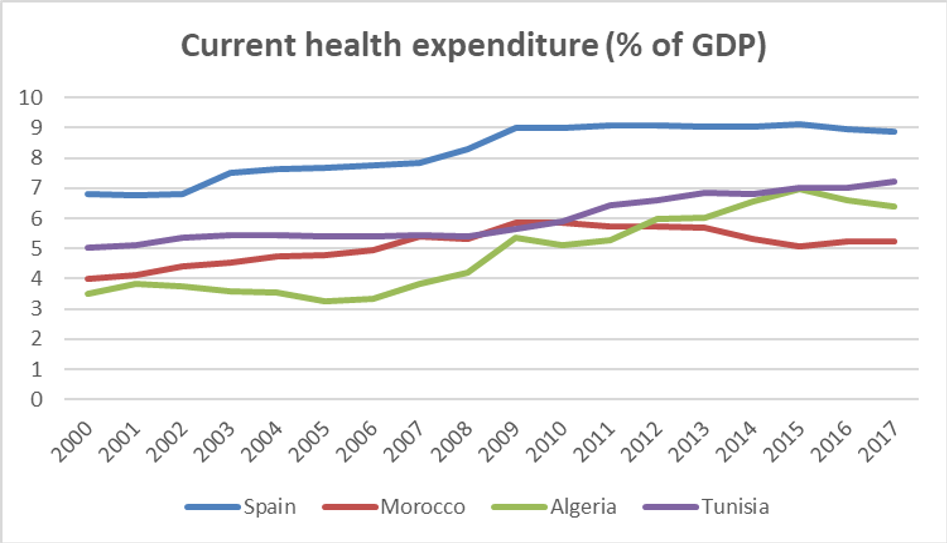

Like many countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, health care has improved overall in Morocco in the past decades. According to the World Health Organization, this is largely due to poverty reduction programs and annual increases in public spending for health and education.[4]In the last decade, health care spending has slightly increased,[5]even though as a percentage of GDP it has actually decreased (see Figure 2 below).There has been a significant decline in under five and maternal mortality, and the threat of communicable diseases has drastically declined. Campaigns to improve immunizations and disease control have successfully eradicated communicable diseases such as polio, malaria, trachoma, and schistosomiasis. While the decrease in communicable diseases is encouraging, there has been a rise in non-communicable diseases, or NCDs (such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases). In Morocco, 75 percent of all death are caused by NCDs.[6]

To target this threat, both the government and non-governmental organizations have embarked on numerous campaigns. National and regional development programs have been a feature of both government policy and Moroccan civil society, and these include significant health care programs. For example, the Foundation Lalla Salma works with the Ministry of Health to fundraise and build essential medical infrastructure to support cancer treatment and research.

Moreover, King Mohammed VI launched the National Human Development Initiative in 2005, which aims to improve the socioeconomic situation of Morocco’s most vulnerable communities. It focuses on cultivating local, national, and international partnerships to reform governance, improve service delivery, and enhance human development.[7] The government has also begun to implement several phases of a regionalization program intending to improve the allocation of public and private services. Decentralizing the health care system constitutes an integral aspect of this process. Morocco’s 2011 constitution enshrines the right to health care, and, according to the World Bank, “In principle, access to free-of-charge public primary health care services is universal. All residents of Morocco are entitled to visit public primary health care facilities and receive services free of charge.”[8]

The Ministry of Health has launched several programs to improve the central problem of poor service delivery. For example, in 2007, it launched a program known as the Concours Qualité (CQ) to improve health care quality at public hospitals and primary care centers. According to a World Bank case study, this self-auditing process, along with management upgrades and funding increases, have incentivized improvements in primary health care.[9]

To tackle challenges of access to healthcare services, several reforms have aimed to increase citizen access to health insurance, including those in the informal sector. Currently, there are two primary public health insurance plans. The first, known as “Compulsory Health Insurance,” was initiated in 2005. It is an employer-based plan for both public and private sector workers, and in a round of 2016 reforms, it was expanded to include higher education students. As of 2017, around 9 million Moroccans received health care through this program, according to the Supervisory Authority of Insurance and Social Security.[10]The second public health insurance option, known as the Medical Assistance regime (RAMED), targets low-income citizens, and includes coverage schemes for those in the informal sector. It was enacted in 2008 and expanded nationally in 2012. This flagship program has substantially increased health insurance coverage.[11]Despite the fact that the program provided insurance for 8.5 million more people, these numbers reveal a deeply troubling reality. According to the High Commission for Planning (HCP), less than half of Moroccans have health insurance.[12]Furthermore, even within the RAMED insurance program, there are problems of low service quality and delays in receiving care.[13]

The most recent national health sector strategy, known as Plan Santé 2025, was agreed to by the Council of Government in April 2018. It was described as a continuation, rather than a replacement of the 2012-2016 and 2017-2021 health care strategies.[14]In theory, it allocated 24 billion MAD for health care investment (14 billion for hospital capacity and 10 billion for national health and disease control programs) between 2019 and 2025. The plan also requires MAD 37 billion from the state budget for its implementation. An additional MAD 24 billion investment budget is financed through the general state budget, loans and PPP, national partnerships and local authorities, international cooperation and new sources of tax revenues.[15] According to the plan, its priorities rest on three key pillars: “Organization and development of care with a view to improving access to health services; Strengthening national health and disease control programs; Improving governance and optimizing the allocation and use of resources.”[16]

One year after the plan was launched, former Minister of Health, Anas Doukkali, himself acknowledged that “The challenges of overhauling the national health system and correcting RAMED’s dysfunctions are certainly resource challenges, but also, and above all, [they are] issues of good governance.”[17]

These improvements and reform efforts represent solid steps in the right direction. The government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis also reveals a high-level of state capacity, meaning that the King and the government were able to mobilize a significant amount of resources and organization to battle the global pandemic. The country has been able to build makeshift hospitals and provide hundreds of beds in a matter of days and weeks.[18] They mobilized a 32.7 billion MAD emergency fund[19] to battle the crisis and have utilized the country’s manufacturing infrastructure to begin producing vital medical equipment such as ventilators and masks.

For now, this has helped keep infection rates lower than many of its MENA neighbors. As of May 9, Morocco has had a total of 5,873 cases and 186 deaths (5 deaths per million). 2,389 have recovered.[20]

However, this short-term success should not overshadow the plethora of structural issues that continue to limit the effectiveness of health care in Morocco. Significant challenges remain and should be addressed to mitigate the risks associated with lifting the lockdown measures, which are expected to take place at the end of May.

Chronic problems of the healthcare sector

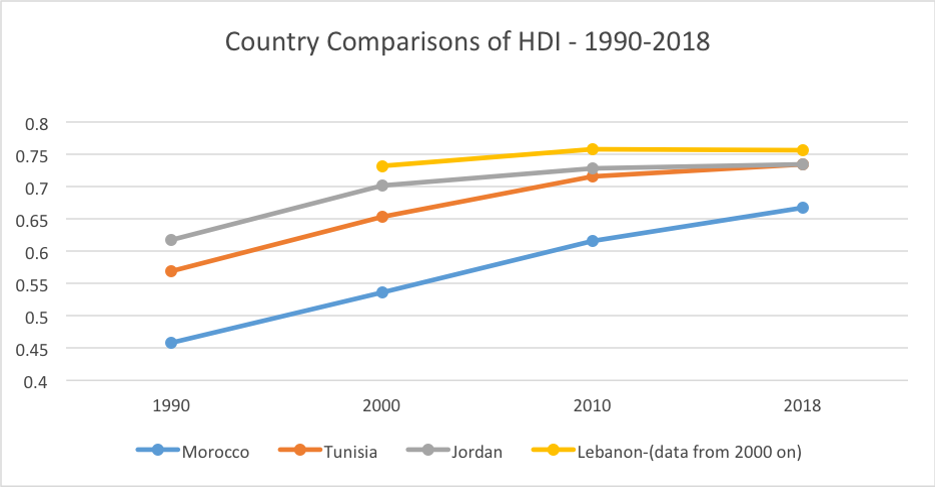

In spite of ambitious development programs and reforms, Morocco’s ranking on the Human Development Index is still very low. In 2018, it was ranked 123 out of 189 countries in the UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI), one of the lowest in the MENA region.[21]

Figure 1: Country Comparisons of Human Development Index 1990-2018

One of the areas that weakens Morocco’s HDI ranking is the healthcare sector.A 2015 World Bank report underlines that, in spite of reforms, “Morocco’s maternal, child, and infant mortality rates— especially in rural areas—are among the highest in the MENA region. According to the national statistics, in 2011 about 10 percent of Morocco’s 13.4 million rural residents and 3.5 percent of its urban residents fell below the national poverty rate.”[22]

Furthermore, as described above, less than half of Moroccans have health insurance, and there has been an alarming rise of non-communicable diseases. In addition to new health challenges and the lack of insurance, the quality of health care in Morocco is low overall. There is a lack of health care workers. In 2017, there was less than one physician per 1,000 people (as compared to 1.3 in Tunisia, 1.8 in Algeria, and 4.1 in Spain).[23]Moreover, there are not enough hospital beds. In 2014, Morocco had 1.1 hospital beds per 1000 people (compared to 2.3 in Tunisia, 1.9 in Algeria, and 3 in Spain).[24]Lastly, even though health care spending has steadily increased, health expenditure as a percentage of GDP is still relatively low. According to World Bank data, it is less than Algeria, Tunisia, and Spain (see Figure 2).[25]

Figure 2: Current Health Expenditure (%of GDP)-2000-2017

While spending is slightly rising, and the government response to the coronavirus crisis revealed a stronger than expected ability to gather significant financial resources, health care spending should make up a larger portion of government spending. It requires further investment than the Plan Santé 2025 offers, especially if the regime hopes to tackle the longer term challenges of both COVID-19 and the underlying public health challenges affecting Moroccan citizens.

However, as the former minister of health noted himself,[26] perhaps the most daunting obstacle to improving overall health care quality and access is good governance.[27] Like many MENA countries, Morocco has embarked on public sector reforms, with various degrees of success, to improve the efficiency and delivery of public services, including health care. Programs like RAMED have helped insure nearly nine million Moroccans, but it still leaves an alarming number of citizens without care. Furthermore, even among those who are insured, other obstacles remain.

Marginalized populations continue to suffer from a lack of access that manifests through various disparities.There are considerable gaps in access to quality health care between urban and rural areas, between public and private hospitals, and between Morocco’s various regions. Most hospitals and health care workers are located in urban areas and along the coast, primarily in Rabat and Casablanca. According to a 2010 WHO study on Morocco, 100 percent of the population in urban areas reside less than 5 km from health care facilities. However, only 30 percent of the population in rural areas live less than 5 km from a health care facility. Nearly 60 percent live between 5 and 10 km away, and 11 percent more than 8 km.[28]This same study lays out significant challenges that remain today, including: “Difficulties in accessing health care for the poorest and for rural populations with a disparity between access and demand of care for certain illnesses, in particular chronic illnesses;[and] Non-satisfactory management of public hospitals, which suffer from a range of inefficiencies, making them unable to compete with private hospitals.”[29]

Part III: Conclusion and Policy Alternatives

The challenges discussed above are not impossible to overcome. Morocco’s rapid response to COVID-19 and its surprising level of state capacity in the face of a public health crisis demonstrate that improving the quality of the healthcare sector depends first and foremost on the existence of political will more than budgetary and governance constraints, at least in the short-term.

As for the long term, it is important to understand the deeper weaknesses in the health care system. Mobilizing resources for short-term crisis management is saving lives in Morocco, and reform efforts over the last two decades have improved the overall state of public health in Morocco. However, there are still considerable challenges in health care quality, as well as the delivery of this essential public service. The government’s goal of universal health care coverage is far from a reality when less than half of Moroccans have health insurance. In other words, the reform efforts thus far have been insufficient.

Moving forward, the government should rely on six priorities to improve the quality and service delivery of public health care.

Increase Spending: While financial resources are not everything, this is a good place to start. The government should increase public spending and seek out more external financing for health care investment and services. The Plan Santé 2025 has highlighted this with their enhanced spending proposal, but given the COVID-19 crisis, this budget should expand even further. It’s important to note that while Morocco’s government spending on health care has increased in recent years, it’s still low compared to other MENA countries. As of 2017, health expenditures represented around five percent of government spending in Morocco, while the global average was ten percent.[30]In this regard, the Moroccan government should consider doubling its health care budget. Furthermore, the World Health Organization underlined that external funding makes up only around one percent of health care financing in Morocco (this is likely higher now, but still low). Morocco is a major recipient of international aid and funding, and more of this should be allocated toward health care.

Policymakers justify the lack of investment in the healthcare sector by emphasizing the lack of financial resources. This can be overcome through decreasing public spending in other areas, such as in the defense budget. Morocco is spending an increasing amount of public funds on purchasing U.S. military equipment. In 2019, Morocco purchased $5billion of military equipment from the United States alone.[31] According to the 2020 finance bill the national defense budget rose by 30 percent.[32]Much of this spending increase relates to the ever-increasing defense budget of regional rival, Algeria. But this approach is short-sighted and unnecessary. Global security is shifting away from traditional threats of conventional warfare and terrorist groups, towards existential threats of climate change and public health. This is even clearer with the spread of COVID-19.

Improve Service Delivery: Morocco’s health care challenge is rooted in a lack of trust. The public has a negative perception of services provided by health care facilities. They think the public health sector performs poorly, and thus they often turn to the private sector (which many cannot afford). In a World Bank study of Morocco’s public medical facilities, researchers found five key areas that enhance health care quality: (1) leadership; (2) team spirit and a shared mission; (3) participation in the Concours Qualité; (4) effective coordination with local and regional officials from the Ministry of Health; and (5) partnerships and community relations.[33] In other words, health care quality can be improved not just through financial resources, but through better utilizing resources such as human capital, by improving the management of resources, and most especially perhaps, by encouraging partnership and collaboration.

Expand Insurance Schemes: A third priority should be to expand health insurance coverage. RAMED needs to transition from targeting low-income communities to becoming a universal health care program. Morocco’s public/private health care systems can remain intact, but a universal public health insurance scheme should be the target for government investment—especially for those living in rural areas. More external funding can be allocated toward this essential service, and the government should use heightened levels of international cooperation surrounding COVID-19 to cultivate health care partnership projects with groups such as the World Bank and the World Health Organization. Doubling the public budget for health care to 10 percent of GDP and thus aligning it better with global standards will help to finance this expansion. Furthermore, Morocco can shift much of its defense spending toward public health security.

Invest in targeted health care sector employment, especially for youth: Implement targeted education and training programs for young people to embark on professions in the health care sector. This could help battle systematic issues relating to youth unemployment, while also tackling the lack of doctors and nurses in Morocco’s public health care system. According to World Bank Data, as of 2017, Morocco has less than one (.72) physician per 1,000 people, Algeria had nearly two (1.8 per 1000), and Spain had more than four (4.1 per 1000 people). The world average is 1.5 physicians per 1000. Similarly, the world average for nurses and midwives per 1000 was 3.4, compared to 1.1 in Morocco.[34]In other words, Morocco needs to double the number of physicians and essentially triple the number of nurses and midwives to catch up with the global average. Furthermore, in the last few years, medical worker unions have been calling for higher wages and greater resources in the public sector.[35]The increases in health care spending should not merely go toward better medical equipment and hiring more doctors and nurses-it needs to also go toward better pay for current health care workers in the public sector. This is an essential aspect of improving the quality of service delivery.

Invest in Medical Equipment Manufacturing: Industrial manufacturing constitutes an essential element of Morocco’s strategy to diversify its economy. It hopes to increase exports and to create jobs by establishing itself as a major manufacturing hub. Both the government and the private sector have been investing in key sectors, such as the automobile industry, agro-industry, aeronautical equipment, and the mining value-chain.[36] The country is seeking to become an industrial manufacturing hub connecting the European, African, Middle Eastern, and perhaps even the Chinese market. Morocco signed a MoU to become an official partner in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2017, and has opened up various special economic zones (SEZs) to encourage foreign investment and infrastructure development and to further develop key industries such as tourism, agriculture, mining, and manufacturing.

Investing in manufacturing health care equipment represents another potential area for diversification. Morocco’s recent success in the mass manufacturing of masks and ventilators is a testament to this. In April, Morocco was producing 5 million masks a day, according to the Minister of Industry, Moulay Hafid Elalamy. The manufacturing capacity was so high that Morocco plans to start exporting them to Europe[37]. This is something that was targeted as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but policymakers should more seriously investigate industrial manufacturing in the health care sector—not just for export to Europe, but to export to its neighbors in the Maghreb and Western/Central Africa, who also lack medical equipment. This fits into Morocco’s economic strategy of triangulation between Western countries (Europe and the US) and Africa.

Enhance Partnerships with local and global stakeholders: COVID-19 is also demonstrating the interconnectedness of public health. One of the main problems with the current global response to the crisis is the lack of global leadership and regional cooperation. One gets the sense that countries are really being forced to handle the pandemic on their own. Many countries, including Morocco, have embarked on swift manufacturing program to produce and export vital medical supplies such as ventilators and masks. Other countries are sending doctors and nurses to countries across the globe. The United States is notably absent from much of these international cooperation efforts. It even announced it would be withdrawing funding from the World Health Organization. In this increasingly fractured global order, countries need to enhance partnerships at every possible level. Domestically, this includes public-private sector cooperation, as well as local-regional-and national level partnerships. This should also encompass regional cooperation with close neighbors—in the case of Morocco, this includes Europe, the Mediterranean region, and the Greater Maghreb, and internationally, this means greater cooperation with groups like the World Health Organization. It’s incredibly challenging, but countries like Morocco need to fight the US-led trend of international disengagement and disregard for global cooperation.

Footnotes

[1] See Yasmina Abouzzohour, “COVID in the Maghreb: Responses and Impacts,” Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS), April 2020, https://pomeps.org/covid-in-the-maghreb-responses-and-impacts.

[2] Mohammed Masbah and Rachid Aourraz, “COVID-19: How Moroccans view the Government’s Measures?” Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA), March 25, 2020, https://mipa.institute/7486.

[3] Ibid.

[4] World Health Organization(WHO), “Morocco: Country Cooperation Strategy at a glance,” May 2018, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136949/ccsbrief_mar_en.pdf;jsessionid=C2096EACC6D53AD889599C7FF9C6B702?sequence=1.

[5] Oxford Business Group, “Morocco ramps up health care spending to build on recent progress,” https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/invested-care-state-has-ramped-sector-spending-latest-budget-build-gains-made-care-recent-years.

[6]WHO, “Morocco: Country Cooperation Strategy at a glance.”

[7] National Initiative for Human Development, http://www.indh.ma/en/home-2/.

[8]Dorothee Chen, “Morocco’s Subsidized Health Insurance Regime for the Poor and Vulnerable Population: Achievements and Challenges,” Universal Health Coverage Study Series, No. 36, World Bank, 2018, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/177741516178542801/pdf/Morocco-s-subsidized-health-insurance-regime-for-the-poor-and-vulnerable-population-achievements-and-challenges.pdf.

[9] Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, “Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank, 2015, p. 94, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607.

[10]Oxford Business Group, “Morocco ramps up health care spending to build on recent progress,” https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/invested-care-state-has-ramped-sector-spending-latest-budget-build-gains-made-care-recent-years.

[11]Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, “Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank, 2015, p. 94, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607.

[12] Morocco World News, “Only 47% of Moroccans Have Healthcare Coverage,” November 14, 2018, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2018/11/257678/47-moroccans-healthcare-coverage/.

[13]Observatoire Nationale du Developpement Humain, “Evaluation du RAMed Rapport annuel de l’Ondh 2017,” http://www.ondh.ma/sites/default/files/documents/presentation_ramed.pdf.

[14] Medias24, “Plan Santé 2025: Les détails de la nouvelle stratégie, » November 13, 2018, https://www.medias24.com/MAROC/SOCIETE/187584-Le-Plan-Sante-2025-devoile-par-Anas-Doukkali-voici-ses-details.html

[15] Ibid.

[16]Ibid.

[17]Medias24, “Plan Santé 2025 : Annas Doukkali fait son premier bilan d’etape, » June 10, 2019, https://www.medias24.com/plan-sante-2025-anas-doukkali-fait-son-premier-bilan-d-etape-2746.html

[18] Fahd Iraqi, “Covid-19 : le Maroc met les bouchées doubles pour accroître sa capacité hospitalière,” Jeune Afrique, April 7, 2020, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/923332/societe/covid-19-le-maroc-met-les-bouchees-doubles-pour-accroitre-sa-capacite-hospitaliere/.

[19]Medias24, “Les dotations au Fonds Covid-19 dépassent désormais 32,7 milliards de DH,” March 28, 2020, https://www.medias24.com/les-dotations-au-fonds-covid-19-depassent-desormais-32-milliards-de-dh-8939.html.

[20]COVID-19 Data, May 7, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeADemocracynow(2020)%20dvegas1?#countries.

[21]Ambassador Edward M. Gabriel , “Morocco rated 123 out of 189 countries in the Human Development Index in 2018,” Morocco on the Move, https://moroccoonthemove.com/2018/09/20/morocco-rated-123-out-of-189-countries-in-the-human-development-index-in-2018-ambassador-edward-m-gabriel-ret/.

[22]Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, “Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank, 2015, p. 93, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607.

[23] World Bank Database, “Physicians (per 1,000 people),” 1960-2017, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=MA.

[24] World Bank Database, “Hospital Beds (per 1,000 people),” 1960-2014, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=MA.

[25]World Bank Database, “Current health expenditure (% of GDP),” 2000-2017, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=MA-DZ-TN-ES.

[26] Medias24, “Plan Santé 2025: Anas Doukkali fait son premier bilan d’étape,” June 10, 2019, https://www.medias24.com/plan-sante-2025-anas-doukkali-fait-son-premier-bilan-d-etape-2746.html.

[27]Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, “Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank, 2015,https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607.

[28]Hassan Semlali, “The Morocco Country Case Study: Positive Practice Environments,” Global Health Workforce Alliance, 2010, p18 https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/PPE_Morocco_CaseStudy.pdf.

[29] Ibid., p 22.

[30] According to WHO, “[G]lobal health spending continues to rise rapidly – to US$ 7.8 trillion in 2017, or about 10% of GDP and $1,080 per capita – up from US$ 7.6 trillion in 2016. About 60% of this spending was public and 40% private, with donor funding representing less than 0.2% of the total.” See World Health Organization, “Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition,” 2019, https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/health-expenditure-report-2019.pdf?ua=1.

[31] Middle East Monitor, “Morocco purchases 25 US aircraft in country’s largest arms deal,” March 27, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190327-morocco-purchases-25-us-aircraft-in-countrys-largest-arms-deal/.

[32] Morgan Hekking, “Morocco’s National Defense Budget to Increase by 29 %,” Morocco World News, October 21, 2019, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/10/285069/morocco-national-defense-budget-increase/.

[33]Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, “Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank, 2015, p. 95, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607.

[34] World Bank Database, “Nurses and midwives per 1000 people,” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sh.med.numw.p3. The world average number is from 2015 and the Morocco average is from 2017.

[35] See Mary A. Bernard, “Across Morocco, No Doctor to be Found,” U.S. News, July 10, 2019, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2019-07-10/moroccos-doctors-medical-students-protest-privatization; Saad Guerraoui, “Moroccan doctors’ strike highlights public health-care problems,” The Arab Weekly, January 28, 2018, https://thearabweekly.com/moroccan-doctors-strike-highlights-public-health-care-problems; and Aida Alami and Simeon Lancaster, “Moroccan medical students decry working conditions,” Aljazeera English, November 28, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/11/moroccan-medical-students-decry-working-conditions-151129114114867.html.

[36] Oxford Business Group, “Manufacturing industry central to Morocco’s exports,” https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/new-ecosystem-manufacturing-becoming-central-kingdom%E2%80%99s-exports.

[37] Des masques marocains certifiés par l’armée française, Media 24, Mai 8, 2020.

https://www.medias24.com/des-masques-marocains-certifies-par-l-armee-francaise-10129.html[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Anna Jacobs

Anna Jacobs is an independent researcher based in Doha, Qatar. She currently works as the senior research assistant for the Brookings Doha center. She was formerly the Academic Director for the SIT Study Abroad program, Field Studies in Journalism and New Media, as well as a lecturer in politics and media at the Ecole de Gouvernance et d'Economie (EGE) in Rabat. She also worked as a freelance political risk consultant on Morocco and Algeria. Her research has primarily focused on politics in the Maghreb, democratization and political reform in the Middle East and North Africa, media and civil society, and migration, as a student at the University of Virginia, the University of Oxford, and as a Fulbright Scholar in Morocco. She was most recently published with Public Books, The Brookings Markaz Forum, Jadaliyya, and Muftah magazine.