[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Although Morocco declared a state of health emergency in real time, it remains unprepared to face the challenges threatening public health

Download article

Abstract

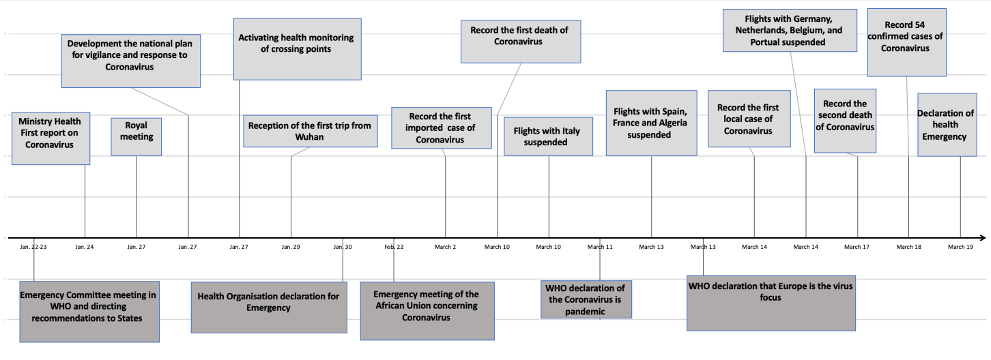

This paper deals with Morocco’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic by declaring the state of health emergency in the real time as an administrative procedure, both internationally and nationally, aiming at containing the epidemiological situation at the beginning of the outbreak. This declaration is based on Morocco’s commitment to implementing the revised International Health Regulations (2005). Accordingly, we are tracking the various measures Morocco has taken to declare health emergencies, beginning with the first communiqué of the Ministry of Health on January 24th, 2020, and the development of the “National Plan for Vigilance and Response to Coronavirus Infection, COVID-19” on January 27th within the work of the National Center for Emergency Operations in Public health, and up to the timely declaration of the state of health emergency on March 19th, 2020 and the accompanying measures.

Introduction

After Morocco announced the state of health emergency at the end of March 2020, there was a general feeling[1]that the authorities—especially the Ministries of Interior and Health—were effective in managing the coronavirus –COVID-19 crisis. This feeling, in our point of view, stems mainly from the timing of the emergency declaration, which we assume was an appropriate time that enabled the control over the pandemic situation at the beginning of the crisis.

In fact, the declaration of the state of health emergency is, in general, an important administrative procedure, both internationally and nationally, in that it helps contain epidemics in accordance with the strategy of vigilance and preparedness adopted by the World Health Organization. Therefore, it is considered to be a component of assessing tools of both the World Health Organization and State Parties’ policies and their rational management of public health emergencies, especially when this announcement is made in real time.

On the other hand, the delay in declaring the state of emergency exacerbated the health crisis and made it difficult to control it, and this is what happened, for example, in the case of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in March 2014, when the World Health Organization was late in declaring the emergency for a few months. Therefore, it was difficult for the WHO to coordinate an international response, which cost the organization severe criticism that it admitted later in an internal report.

We will monitor the components and procedures that contributed to producing the real time for the declaration of the state of health emergency in Morocco, as this practically translates into the engagement in the strategy for public health crisis preparedness for more than a decade. We will start with an overview of the legislative and the institutional framework as well as the measures taken after the WHO declared a global health emergency. Then, we will tackle the pandemic surveillance at the onset of the outbreak. Finally, we will analyze the constituents of real-time production.

-

The legislative and institutional framework for preparation

The declaration of the state of health emergency by a specific state in coordination with the World Health Organization is considered a response to avoid the outbreak of the disease on its territory. It is a declaration organized by the revised International Health Regulations (2005) as the framework that implements global health security.[2]The purpose and scope of the IHR (2005) are “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease”[3]. This situation means taking a set of measures at the health level, such as: quarantine[4], isolation, follow-up, check-up, and care… etc., as vital policy mechanisms in order to “address threats by prohibiting them –by attempting to spatially block their encroachment”[5].

Morocco, in turn, joined this path as a State Party to the International Health Regulations after signing it in 2005 and issuing it in the Official Gazette[6] on October 26th, 2009, and committed itself to strengthening its capabilities permanently and diligently within its framework according to a gradual policy, starting with the four-year health schemes of (2008-2012) and (2012-2016), through its preparedness to confront Ebola in 2014, then through the assessment[7] of the strengths and weaknesses by the World Health Organization in a report issued in 2016(see Document 1), and ending with the establishment of the National Center[8] for Emergency Operations in Public Health in accordance with activating the “2025 Health” plan and the directives of the Health Organization, which issued a recommendation in this regard in November 2015.

Document1: Challenges of the International Health Regulations implementation according to the 2016 assessment report on “Essential Functions of Public Health in Morocco”

| The report identified the main challenges for implementing the International Health Regulations in Morocco, as follows: 1) Setting up an emergency preparedness plan that is inclusive, multi-sectoral, and multi-disciplinary. 2) Defining a clear policy and institutional framework for planning, organizing and implementing emergency preparedness and response plan in the field of public health. 3) Working towards converging regulation, management and supervision in the operation of laboratories in order to support the basic functions of public health. 4) Supporting and supervising the periodic evaluation of the progress made in the rehabilitation of basic capabilities in the field of public health embedded in the International Health Regulations. |

Source: “Evaluation of the Basic Functions of Public Health in Morocco” Report (pp. 29-30)

This process provided the necessary legislative and institutional framework to manage the pandemic situation related to the coronavirus – COVID-19 on multiple levels, such as structures, equipping land crossing points, ports and airports, the national network of laboratories, medical equipment, stock of medicines and protective gear, mechanisms of transportation, diagnosis and care/accommodation, setting up a system for reporting risks, strategies and mechanisms for communication with the media and the population, governance and coordination … etc. However, the National Center for Emergency Operations in Public Health remains the primary institution entrusted with vigilance, early warning and technical management of health emergencies as “a critical tool for rapidly and effectively responding to potential public health emergencies”[9].

2. Procedures of vigilance and early warning

The process of Morocco’s management of COVID-19 (Figure 1) began with the first communiqué issued by the Ministry of Health on 24th January 2020. This communiqué stated that “the Emergency Committee of the International Health Regulations in the World Health Organization met and decided not to declare that the event is “a public health emergency that calls for an international concern “at the present time, and, therefore, it does not recommend imposing restrictions on international travel or trade”. It also stressed that the ministry “works to monitor the disease through the national system for pandemic surveillance and has prepared everything related to the means of viral diagnosis and prevention.” On January 27, King Mohammed VI chaired[10] a working session in the presence of Prime Minister Saad Eddine El Othmani, King’s Adviser Fouad Ali El Himma, Minister of Interior Abdelouafi Laftit, Minister of Foreign Affairs, African Cooperation and Moroccans Residing Abroad Nasser Bourita, Minister of Health Khaled Ait Al Taleb, and General of the Army Corps Mohamed Hormo, the Royal Gendarmerie Commander. The working session was dedicated to the status of Moroccan citizens in the Chinese province of Wuhan, which the Chinese authorities have placed under lockdown following the coronavirus outbreak. The king gave his “instructions to help the 100 Moroccan citizens who are in this region—the majority of whom are students—return to the homeland.” He also ordered that “necessary measures be taken at the level of air transportation, adequate airports and special health infrastructure for reception.” On the same day, the Ministry of Health announced in a communiqué that it had begun “health monitoring of international ports and airports for early detection of any imported cases and halting the spreading of the virus”, noting that “the Ministry of Health still considers that the risk of the virus spreading in the national territory is weak, and that no case was recorded until that day.” Here, we should wonder what regulations Morocco was referring to launching port and airport monitoring before the World Health Organization announced that the event was a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”(PHEIC).

It is clear that Morocco referred to the statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee held at the World Health Organization on January 22ndand23rd, 2020—and it was referred to in the press release of the Moroccan Ministry of Health on January 24th—in which the organization “expected that further international exportation of cases may appear in any country. Thus, all countries should be prepared for containment, including active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, contact tracing and prevention of the onward spread of 2019-nCoV infection, and to share full data with the WHO.”[11]Based on this directive to the State Parties, Morocco activated the monitoring of ports and airports although the organization did not declare the event a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern.” What reinforces Morocco’s resort to this procedure is that the organization’s meeting indicated that the novel Coronavirus had spread to South Korea, Japan, Thailand and Singapore, all of whom took part in the meeting of the members of the Emergency Committee and provided data on the development of the disease on their lands. Although the committee did not advise that the disease represented a “public health emergency that calls for international concern “based on the aforementioned countries testimony, but they “agreed on the urgency of the situation and suggested that the Committee should be reconvened in a matter of days to examine the situation further.”[12] This happened less than a week later, when the World Health Organization declared[13]at the second meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, held on January 30th, 2020, the novel COVID-19 a “public health emergency of international concern” after the committee recommended the Director-General of the organization should make the declaration. In the same meeting, it was advised that “all countries should be prepared for containment, including active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, contact tracing and prevention of the onward spread of 2019-nCoV infection, and to share full data with the WHO.”[14]. There is no need to clarify that this decision was made by the organization based on Article 12 of the regulations “WHO shall consult with the State Party in whose territory the event is occurring as to its intent to make information available under this Article. The Director-General shall determine, on the basis of the information received, in particular from the State Party within whose territory an event is occurring, whether an event constitutes a public health emergency of international concern in accordance with the criteria and the procedure set out in these Regulations. […]the Director-General considers, based on an assessment under these Regulations, that a public health emergency of international concern is occurring, the Director-General shall consult with the State Party in whose territory the event arises regarding this preliminary determination. If the Director-General and the State Party are in agreement regarding this determination, the Director-General shall, in accordance with the procedure set forth in Article 49, seek the views of the Committee established under Article 48 (hereinafter the “Emergency Committee”) on appropriate temporary recommendations”[15].

These successive events at the level of the World Health Organization prompted the National Emergency Center for Public Health affiliated to the Department of Epidemiology at the Ministry of Health to issue a national plan on January 27th to confront COVID-19 entitled: “The National Vigilance and Response Plan of COVID-19 Infection”[16]. It included a serious assessment for the risk, describing the situation that “the risk of COVID-19 importation into the national territory is high, that the risk of human-to-human transmission of the virus through an imported case is moderate, and that the risk of the virus spreading through local transmission at the national level is weak”[17]. This assessment remained valid until February 26th.[18]

On Saturday, February 22nd, 2020, Morocco participated in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, in the emergency ministerial meeting of the African Union regarding the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic. In this meeting, the Minister of Health stated[19] that Morocco had “raised the level of vigilance of the National Center for Emergency Operations in Public Health at the Ministry of Health, from the green level to the orange level” as stated in the national plan, and also “activated the central department to coordinate health sector measures with those of the Ministry of Interior, the Gendarmerie Royale, military health services, and other sectors involved.” pointing out that “Morocco is committed to its obligations under the International Health Regulations and has not imposed any restrictions on travel or on the movement of goods with the affected countries, recalling the health control at entry points (airports, ports and land entry points). ” In all this, it appears that Morocco is keen on following the directions of the World Health Organization in managing the crisis.

Figure 1: Timeline for the declaration of health emergency in Morocco

3. Epidemiological surveillance at the beginning of the spread

Despite the activation of health control at airports and ports, infected individuals came across the borders, as is evident in the Ministry of Health’s communiqués. Thus, the first case was recorded on March 2nd[20], of a man who entered Morocco via Mohammed V Airport on February 27th from Italy. Then other cases followed; On March 4[21], a woman coming from Italy, on March 10[22] the first death, and on the same day the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a decision to suspend all flights from and to Italy after it was proved that health monitoring was quite futile in preventing the entry of the disease despite conducting more than 35,012 checks[23] at entry points between January 26th and March 8th. The Moroccan government then suspended flights from and to Spain, France and Algeria on March 13th[24], and then Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Portugal on March 14th[25]. After that, on March 13th, the Ministry of Health announced 8 cases. On March 14th, nine other cases were added: 4 from Spain, 3 from Italy, and one from France. It is striking that this communiqué indicated that these cases entered Morocco between February 24th and March 12th, and headed towards: Tetouan, Rabat, Casablanca, Fez, and Khouribga.

On March 14th, the first local case of infection was recorded through its contact with another imported case that had previously been confirmed, that is, a local case was recorded, not an imported, raising the total number to 17. This makes the patient zero difficult to determine, but we can imagine the size of the infection that these people caused during the previous days before their infection was confirmed. In another communiqué on March 15th [26], 11 other cases were added, including 6 from Spain, two from France, two other cases from Italy and one from Austria, raising the total number to 28.

In a communiqué on March 17th[27], the second death was recorded, and a communiqué of the Ministry of Health announced that the number of cases had reached 44 cases. The cases included imported cases distributed over the following cities: two cases in Tangiers, one in Oujda, one case in Rabat, one case in Settat, and one case in Guelmim). On March 18th[28], the Ministry of Health issued a communiqué announcing that the number of cases had reached 54 confirmed cases, and that the additional cases were related to cases who had contact with infected people in the Fez-Meknes region. Thus, the numbers multiplied in an exponential way, which urged Morocco to declare a state of health emergency on March 19th[29]. This was evident in the March 21st communiqué when the number of cases doubled to reach 96 cases, distributed in various regions of Morocco.

Table 1: The evolution of the number of cases and deaths in Morocco before the declaration of the health emergency

| Day (*) | March 2nd | March 4th | March 10th | March 13th | March 14th | March 15th | March 17th | March 18th |

| Injuries | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 17 | 28 | 38 | 54 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

(*) We relied on the Ministry of Health reports, which were not issued daily during this period. We would like to point out that there is a discrepancy between the figures of the Ministry of Health and those of the World Health Organization. Therefore, we adopted those of the main source in the table, which are based on the Ministry of Health’s statements.

Source: Department of Epidemiology, Ministry of Health

In parallel with controlling and tracking the pandemic situation at the national level, Morocco was observing the course of the pandemic situation globally, especially the directives of the World Health Organization. Thus, Morocco was attentive to the WHO Director-General’s declaration stating that the threat of the virus has become more real, classifying the epidemic as a global pandemic[30] on March 11th, 2020, and considering Europe as the new focal point of the pandemic on March 13th[31].The relevance of Europe lies in the fact that it has close relations with Morocco, and in the active circulation of people and goods between Morocco and Europe. Besides, the cases recorded on this date were all coming from Europe. To this date, March 18th, cases around the world reached 191,127 cases and 7807 deaths[32], in Italy, the second affected country after China, reported 31,506 cases, 3,231 deaths, and 345 daily deaths. In Spain, 11,178 cases, 491 deaths, and 182 daily deaths[33] were reported. At this time, the health emergency procedures in Morocco had to be implemented in every respect especially that the country moved from the imported to the locally contracted cases, as stipulated in the communiqué of March 14th. Thus, Morocco was in front of all forms of danger identified by the national plan on January 27th, including what it described as the low probability of the disease transformation into local spread.

-

The declaration of emergency in the real time

We can outline the elements of producing the real time to confront COVID-19 in Morocco in four points:

It is indicated that Morocco activated the National Center for Emergency Operations, worked with the early warning system, and prepared the national plan to confront COVID-19, and was following up the pandemic situation at the national and international levels through the five epidemiological status reports it published before the emergency declaration. Thanks to these measures, Morocco was able to declare the emergency in time, especially if we look at the declaration timing of health emergencies in other countries that remained in control of their epidemiological situation (Tunisia, Canada, etc.) in contrast to those that were late in declaring a state of emergency (Spain) and where the pandemic went out of its control. (Table N° 2)

Table N° 2: Comparison of the emergency declaration with the number of cases and deaths in a selected group of countries in the world

| Country | The date of health emergency declaration | Number of cases on the date of the declaration of a state of emergency (*) | Number of deaths on the date of the declaration of a state of emergency (*) |

| Morocco | March 19, 2020 | 54 | 2 |

| Tunisia | March 18, 2020 | 24 | 0 |

| Canada | March 17, 2020 | 424 | 1 |

| Argentina | March 19, 2020 | 79 | 2 |

| Spain | March 13, 2020 | 2965 | 84 |

| South Africa | March 26, 2020 | 709 | 0 |

| South Korea | Feb. 23, 2020 | 602 | 5 |

(*)Regarding the data of the number of cases and deaths, we relied on the daily epidemiological situation report of the World Health Organization.

Source: World Health Organization

Conclusions and recommendations

Despite the announcement in the real time thanks to the series of strengthening capacities required by the International Health Regulations, it appears that Morocco suffers from the gaps in the preparedness indicated in the 2016“Fundamentalfunctions Assessment …” report. Perhaps it is because of Morocco’s bad luck that the pandemic came a few months after the establishment of the National Center for Emergency Operations in Public Health (September 2019), which did not accumulate all the possible work tools, the necessary specialized expertise and sufficient human resources, bearing in mind that the Ebola response plan had not come into effect in 2014. This was an additional factor in the lack of the practical test of Morocco’s actual capabilities to face threats.

In the wake of the unprecedented COVID-19 event in its disastrous results, Morocco must step up accelerating its core capacity-building. The assessment report of “Essential Public Health Functions in Morocco” detailed its strengths and weaknesses and made important recommendations that must be taken seriously. The horizon remains the establishment of a national system to prepare for all emergency public health crises in a comprehensive, coherent and integrated manner.

Translated by: Imane Loukili

Footnotes

[1]In addition to the spread of this opinion by observers and trackers, it was also reflected in official and unofficial reports, such as:

Chef du Gouvernement, Les mesures prises par le Royaume du Maroc pour faire face aux répercussions sanitaires, économiques et sociales de la propagation du Covid-19, A travers les réponses du Chef du Gouvernement SaadEdine El Othmani aux questions relatives à la politique générale de parlement, Séance du 13 avril 2020 à la chambre des Représentants et Séance du 21 avril à la chambre des Conseillers, Avril 2020, Royaume du Maroc.

Abdelaziz Ait Aki, Abdelhak Bassou, M’hammed Dryef, Karim El Aynaoui, Rachid El Houdaigui, Youssef El Jai, Faiçal Houssaini, Larab iJaidi, Mohamed Loulichki, El Mostafa Rezrazi Abdellah Saaf, La Stratégie Du Maroc Face Au Covid-19, Policy Paper N° 20-07, Avril 2020, Policy Center For The New South.

Mohamed Masbah and Rachid Aourraz, “COVID-19: How Moroccans view the Government’s Measures?”, Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA), March 22, 2020: https://mipa.institute/jorifiq/2020/03/CORONA-MOROCCO.pdf

[2]Lawrence O. Gostin and Rebecca Katz, The International Health Regulations: The Governing Framework for Global Health Security, In :Global Management of Infectious disease after Ebola, Edited by Sam F. Halabi, Lawrence O. Gostin and Jeffrey Crowley, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp 101-132.

[3]World Health Organization, International Health Regulations (2005), third edition, Geneva, 2016. p 1.

[4]Martin Cetron, Isolation, Quarantine, and Infectious Disease Threats Arising From Global Migration , In :Global Management of Infectious disease after Ebola,Edited by Sam F. Halabi, Lawrence O. Gostin and Jeffrey Crowley, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp 245-255.

[5]Andrew Lakoff, Unprepared: Global Health in a time of Emergency, Berkeley, CA, The University of California Press,2017, p 99.

[6]Dahir n° 1-09-212 du 7 Du Al-qi’dah 1430 (26 Octobre 2009) portant publication du Règlement sanitaire international (2005) adopté par l’Assemblée mondiale de la santé lors de sa cinquante huitième session du 23 Mai 2005.

[7] Ministère de la Santé et Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Evaluations des fonctions essentielles de santé publiques au Maroc; rapport technique, 2016.

[8]Direction de l’Epidémiologie et de Lutte contre les Maladies, CNOUSP: Procédures fonctionnelles et organisationnelles, Ministre de la Santé, Royaume du Maroc. 16-17 Janvier 2019.

[9]Rebecca Katz and James Banaski, Jr. Essentials of Public Health Preparedness and Emergency Management, Jones and Bartlett Learning, second edition, 2019, p 182.

[10]Royal Office communiqué on January 27, 2020.

[11]Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

[12]Ibidem.

[13]Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

[14] Ibidem.

[15]World Health Organization, International Health Regulations…op. cit. p 13-14.

[16] Ministère de la Santé, Plan National de veille et de riposte à l’infection par le Coronavirus 2019-nCov, 27 Janvier 2020, Royaume du Maroc.

[17] Ibid, p 4.

[18] Ministère de la Santé, Bulletin de l’urgence de Santé publique liée au Covid 19, CNOUSP, 16 février 2020. Royaume du Maroc.

[19]https://www.sante.gov.ma/Sites/ar/pages/actualites.aspx?IDactu=396

[20]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 2, 2020

[21]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 4, 2020

[22]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 10, 2020

[23] Ministère de la Santé, Bulletin hebdomadaire (Covid 19), 09 /03/2020, DELM.

[24]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 13, 2020

[25]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 14, 2020

[26]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 15, 2020

[27]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 17, 2020

[28]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 18, 2020

[29]Ministry of Health communiqué on March 21, 2020

[30]WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020

[31]Timeline of WHO’s response to COVID-19: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/29-06-2020-covidtimeline

[32]World health Organization, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report -58. 18 March 2020.

[33] Ibid.

[34]Andrew Lakoff, Unprepared…Op. cit. p 98.

[35] Ibid, p 99.

[36] Ibid, p 98.

[37]World Health Organization, framework for a public health Emergency operations center, November 2015.

[38]Direction de l’Epidémiologie et de Lutte contre les Maladies, CNOUSP… Op.cit.

[39]Ministerial Decision N°. 013065 of September 16, 2019 to establish the National Center for Emergency Operations in Public Health.

[40]Harvey V. Fineberg & Mary Elizabeth Wilson, Epidemic Science in Real Time, Science 22 May 2009: Vol. 324, Issue 5930, pp. 987

[41] Ministère de la Santé, Plan de veille et de préparation à la riposte contre la maladie à Virus Ebola, version 2, Octobre 2014, Royaume du Maroc.

[42] Ministère de la Santé et Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Evaluations des fonctions essentielles…op.cit. p 27.

[43]World Health Organization, framework…op.cit. p 3.

[44]Ibid. p 3.

[45] Andrew Lakoff, Unprepared…Op. cit. p 11.

[46] Ibid, p 103.

[47] Ibid, 97.

[48] Ibid, 96.

[49]SudeepaAbeysinghe, ‘When the spread of disease becomes a global events: the classifications of pandemics’, Social Studies of science, 2013, 43 (6) 905-926.

[50] Ibidem.

[51]World Health Organization, International Health Regulations…op.cit. p 41.

[52] Ministère de la Santé, Plan National de veille et de riposte à l’infection par le Coronavirus 2019-nCov, 27 Janvier 2020, Royaume du Maroc, p 4.

[53] Ibid, p 2.

[54] Ibid, p 5.

[55]World Health Organization, framework…op.cit. p 43.

[56]Available on website ‘Coronavirus in Morocco:

http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Pages/SituationCovidAR.aspx

[57]Andrew Lakoff, Unprepared…Op. cit. p 146.

[58] Ibid. p 24.

References

- Abdelaziz Ait Aki, Abdelhak Bassou, M’hammed Dryef, Karim El Aynaoui, Rachid El Houdaigui, Youssef El Jai, Faiçal Houssaini, Larabi Jaidi, Mohamed Loulichki, El Mostafa Rezrazi Abdellah Saaf, La Stratégie Du Maroc Face Au Covid-19, Policy Paper N° 20-07, Avril 2020, Policy Center For The New South.

- Andrew Lakoff, Unprepared: Global Health in a time of Emergency, Berkeley, CA, The University of California Press, 2017.

- Chef du Gouvernement, Les mesures prises par le Royaume du Maroc pour faire face aux répercussions sanitaires, économiques et sociales de la propagation du Covid-19, A travers les réponses du Chef du Gouvernement SaadEdine El Othmani aux questions relatives à la politique générale de parlement, Séance du 13 avril 2020 à la chambre des Représentants et Séance du 21 avril à la chambre des Conseillers, Avril 2020, Royaume du Maroc.

- Direction de l’Epidémiologie et de Lutte contre les Maladies, CNOUSP: Procédures fonctionnelles et organisationnelles, Ministère de la Santé, Royaume du Maroc. 16-17 Janvier 2019.

- Harvey V. Fineberg& Mary Elizabeth Wilson, Epidemic Science in Real Time, Science 22 May 2009: Vol. 324, Issue 5930, pp. 987

- Martin Cetron, Isolation, Quarantine, and Infectious Disease Threats Arising From Global Migration , In :Global Management of Infectious disease after Ebola, Edited by Sam F. Halabi, Lawrence O. Gostin and Jeffrey Crowley, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp 245-255.

- Ministère de la Santé, Plan de veille et de préparation à la riposte contre la maladie à Virus Ebola, version 2, Octobre 2014, Royaume du Maroc.

- Ministère de la Santé, Plan National de veille et de riposte à l’infection par le Coronavirus 2019-nCov, 27 Janvier 2020, Royaume du Maroc.

- Mohamed Masbah and Rachid Aourraz, “COVID-19: How Moroccans view the Government’s Measures?”, Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA), March 22, 2020: https://mipa.institute/jorifiq/2020/03/CORONA-MOROCCO.pdf

- Rebecca Katz and James Banaski, Jr. Essentials of Public Health Preparedness and Emergency Management, Jones and Bartlett Learning, second edition, 2019.

- SudeepaAbeysinghe, ‘When the spread of disease becomes a global events: the classifications of pandemics, Social Studies of science, 2013, 43 (6) 905-926.

- World health Organization, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report -58. 18 March 2020.

- World Health Organization, framework for a public health Emergency operations center, November 2015.

- World Health Organization, International Health Regulations (2005), third edition, Geneva, 2016.

- World Health Organization, Public Health Emergency Operations Center Framework, November 2015, Geneva, 2017.

- Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

- https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

- https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/23-01-2020-statement-on-the-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020

- https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- The Ministry of Health, the official portal of the Coronavirus in Morocco, reports http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Pages/CommuniquesAR.aspx

- The Ministry of Health, the official portal of the Coronavirus in Morocco, the epidemiological situation: http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Pages/SituationCovidAR.aspx

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Loukili Youness

He is a research Professor at the University Institute for Scientific Research, University of Mohammed V, Rabat. He specializes in the sociology of Islam. He also works on anthropology of health and disease, and the sociology of health emergencies. He edited and published numerous studies and books, the most recent of which are: “Understanding Religious Extremism: Ideology, Social Cases, and Attempts to Moderation” (2017), and “French Anthropology: Studies and Reviews in the Legacy of Émile Durkheim and Marcel Moss” (2018), and “Preventive health measures as a political and social matter in the context of Covid-19 in Morocco” (2020). Moreover, he will soon publish a book, "Anthropology of Healing: Roquia and the Conflict of Patterns of Religion" (2021).