[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Download report

Why should we study trust? Simply put, trust is the glue of society. It is one of the first things we learn at birth, and it underscores our relationships with others: our actions are grounded on trust. In daily life, trust exists everywhere, from trusting the taxi driver to get you to the right destination safely, to trusting the barber to use his sharp razor around your neck, or simply walking safely in the street without fear of being assaulted. Without trust, society cannot hold itself up. Families would lack the connection that binds them together, and institutions would lack the power and legitimacy to govern. This network of interactions is the foundation on which society is built, and governments are legitimatized only by a collective trust in them. In fact, a government can use excessive power and violence to govern for the short term but for the long-term it needs to garner people’s trust, otherwise, it cannot sustain itself.

As trust is everywhere, people tend to take it for granted. It is so entrenched in our society that recognizing and appreciating its value can prove difficult. However, breaking down components of trust, quantifying them, and analyzing them can foster a clearer understanding about our societies that we would not recognize otherwise. And because trust is the glue that holds society together, studying it helps us identify the cracks in its foundation and provides pathways to restoring it. The study of trust allows us to explain social and political connections and disconnections in society and – more importantly – suggest the steps to take in order to fix them.

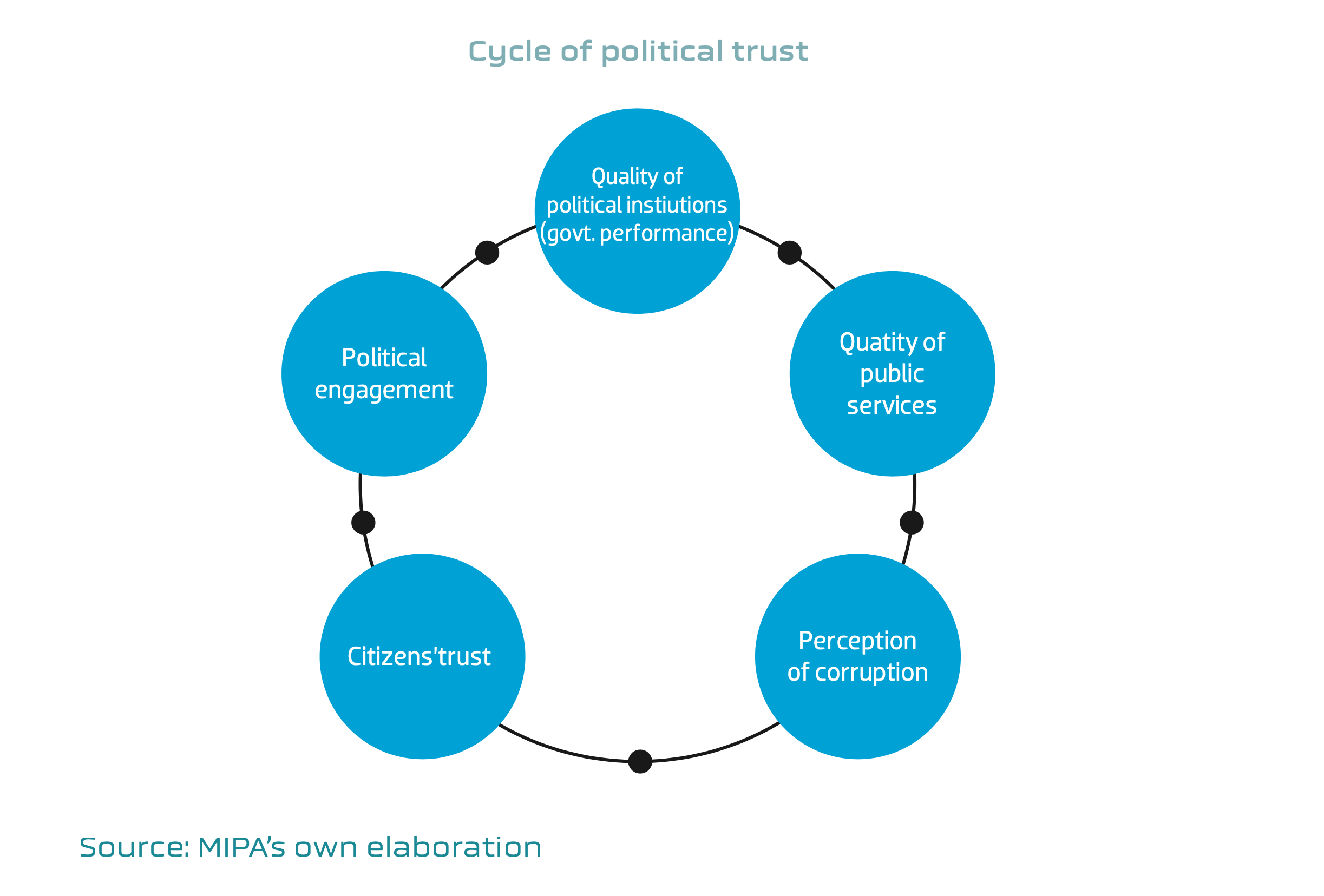

Understanding social and political trust has benefits not only for research but also for the policy realm. Firstly, it helps researchers and decision makers to understand the complex relation between trust in institutions on one hand and government performance, perceptions of corruption, (in)formal political participation on the other. Secondly, it provides insights on the underpinnings of democratic deficits and difficulties that elected institutions, such as the Parliament and political parties, face. Finally, studying political trust and distrust helps to identify the gaps and factors leading to distrust and lays down the road to reverse the vicious circle of poor-performance, perception of corruption and political disengagement.[1]

In this regard, the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis dedicated this annual report to study social and political trust in Morocco, with the aim to contribute to the academic and policy debates on social and political trust, and to propose alternative policies and feasible recommendations to help restore confidence in public institutions.

Morocco provides a good case study for social and political trust. It is characterized by a low institutional trust, while it maintains a relatively strong social bonds and highly level of trust in personalized trust, such as the family and kinship. The results of this study reveal that family is the most trusted social institution. As the social circle expands – colleagues, neighbors and people you may encounter on a daily basis – the levels of trust tend to decrease. The least trusted part of society is strangers or people whom are met the first time, in addition to people from other religions, nationalities or sexual orientations. It should also be noted that there is a growing feeling, especially among older generations, that the general levels of trust in society have overall declined in the last few decades.

While trust in close social groups is high, trust in political institutions remains generally low. Moroccans are skeptical about the government performance and its ability to provide good services, especially in education and health. They are also unsatisfied about the performance of the economy and are highly disappointed by the government’s efforts in fighting corruption. Most likely, this is also related to the increased interest in informal political participation in recent years, such as the economic and electoral boycott and protests. While political parties and elected institutions are seen as underperforming, useless, and lacking trustworthiness, the only trusted institutions are the monarchy and the security apparatus.

Likewise, the Parliament is one of the least trusted institutions. Members of Parliament interviewed in this study interpreted this situation by the role of social media in showcasing a negative image of the Parliament and reduced their credibility in the eyes of the public. The deficiency of institutional communication by the Parliament makes citizens unaware of the actual efforts of MPs in discussing laws and regulations. In turn, this played into the perception that MPs were rent seekers. In the absence of resources such as skilled staff and lack of office space within the Parliament, MPs cannot properly conduct their work as legislators. Finally, the electoral law combined with archaic party structures produced a parliamentary elite that is not necessarily based on meritocracy or competence, but rather on political loyalty and cronyism.

How to explain political distrust?

The nexus between government performance, quality of public services, and perceptions of corruption in the government bureaucracy is central to understanding the low levels of trust in political institutions. Furthermore, these are the key elements to explain the resort to informal channels for political engagement. In 2015, the World Bank released a report on the relation between trust, voice, and incentives. One of the main findings is that poor performance of public institutions in the MENA regions led citizens to perceive government as corrupt and ineffective and hence reinforced their disengagement and increased the perceptions of distrust.[2] Morocco is a country with high level of (both perceived and real) corruption, which is one of the factors that cause citizens’ distrust in the political institutions – hence providing the ground for political contestation.

Consequently, the plummeting trust in public institutions leaves citizens with few options to engage in the formal channels to fulfill their needs, thus reinforcing informal social networks (Wasta) and corruption. The World Bank team concludes that without dependable institutions and citizens’ trust in them, there is little formal citizen engagement, institutions remain stagnant, and service delivery is poor[3].

In this regard, this report proposes an ideal-model that links political trust to government performance and communication strategies, perceptions of corruption, the quality of public services and the trustworthiness of individual political actors.[4] Such ideal-model serves as a mean to explain and simplify the complex realities, and hence cannot explain all the cases. Nevertheless, they are useful tools to provide sense to the complex reality. In this regard, the model this report proposes can be simplified as the following.

This annual report is divided into three sections that contain the analyses of the field research related to social and political trust in Morocco.

The first section will discuss Social Trust, including trust in family, neighbors and others. It will first discuss the importance and relevance of social trust, the role of personal experience and socialization in simmering the perceptions of social trust. It will also examine and explain the sources of trust, specifically looking at family, and at the role of religion and moral values. Finally, it will describe and analyze the different levels of social trust in the different categories of interpersonal relations, such as the family, friends and neighbors, and trust in others and in strangers.

The second section will study Political Trust, and especially the difference between trust in elected and non-elected Institutions. It will explain how and why the trust is low in the elected executive branch (the Government) and in political parties, as well as in institutions dedicated to public service delivery, such as education and healthcare. It will also look at the high level of trust in the security apparatus. Special attention will be dedicated to institutions that mediate between citizens and the state – civil society organizations (CSOs) and labor unions.

While the first and second sections will research the evolution of social and political trust over the years, the final section will look in-depth at a specific institution. This year, MIPA decided to work on the Parliament, which will be the subject of discussion in the final section of this report, namely the Trust in the Parliament. A particular interest will be devoted to components that affect trust in the Moroccan Parliament. Concretely, it will look at the trustworthiness, capabilities, performance and communication of the Parliament as an institution and members of Parliament as actors of this institution. Crosscutting issues, such as social contract, confusions about the roles of MPs, will be discussed as well.

At the end of the report, we provided a literature review that aims at providing a broad overview of the current research on trust – empirical investigations, global and regional analyses, and their theoretical implications. While it is by no means a substitute for the studies themselves, the review will discuss their common trends and findings as well as identify the missing elements that need to be addressed.

Unpacking the findings on social and political trust in Morocco will shed light on those social and political institutions that are trusted the most, and those that lack the same confidence, thus exposing the strengths and malfunctioning of the main institutions in Moroccan society. Furthermore, the analysis of the trust in the Parliament will provide a clarification on the key issues that revolve around the lack of trust in this central institution for the functioning of democratic life. Grounded on original empirical data, MIPA’s study of trust has the objective of both contributing to the discussion on trust in Morocco and suggesting the first key steps to renovate trust in institutions.

Methodology

This report is the fruit of rich and dense data collected from fieldwork throughout 2019. It is based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative research techniques.

The quantitative analysis was based on a sample of 1,000 people in October 2019, targeting Moroccans aged 18 and over. The representative nature of the sample was ensured by the quota method (sex, age, and geographical area) according to the structure of the Moroccan population designed by the High Commission for Planning (RGHP 2014). The questions of the survey constituted about 84 variables via CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews).[5]

Concerning the sample of the survey, half of the participants were women and the other half were men. The under-29 age group represents about 31%, while the over-50 age group represents about 28.7%. In terms of geographic distribution, the Atlantic coast regions accounted for 37%, the centre regions for 18.6%, the north regions for 16.7%, and the south regions for 27.6%. 35% of those surveyed live in rural areas, while 65% of them live in urban areas. In terms of average wages, households with an income of less than 8,000 dirhams per month make up the largest share of the sample: 57% of the respondents (32 people had a salary of less than 3,000 dirhams, and 25 people had a salary between 3,000 and 8,000 dirhams). As for their education levels, 14% of respondents had an elementary education level, and 13% of respondents were illiterate. Survey data will be made publicly available on MIPA’s website to increase transparency, as well as to provide other researchers with the possibility to make use of the potential of the data collected for this research.

In terms of qualitative analysis, the report relies upon the ‘grounded theory’ approach, which is a methodology based on the construction of analytical frameworks through a dense and structured set of field data.[6] In this regard, the in-depth interview technique was used with semi-structured questions with 23 participants from the cities of Casablanca, Rabat and Marrakech during the period between mid-September to late October 2019. It included a diverse sample that considers gender equality and socio-economic diversity. The interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes per participant. In addition, in-depth individual interviews were conducted with seven MPs and a staff member from the House of Councillors. Moreover, three focus groups were organized with about 16 participants in total: one for businessmen, another for labour unions, and the third for local elected officials and political activists. The duration of each focus group was about 2 hours. The names of the interviewees have been concealed in order to ensure the anonymity and the protection of the privacy of the research participants.

After collecting the data, the team worked on the analysis of the report, which has been done in five phases: in the first phase, the research team transcribed all the interviews in the original language, and made a quality control check to make sure of the accuracy of transcription. This phase was followed by the coding of each of the interviews by identifying the main themes and sub-themes. After the identification of the main and sub-themes, the researchers wrote memos in the form of short notes that resumed the main concepts. Then they worked on formulating the main categories for the analysis by developing the memos into a more coherent analysis, which constituted the backbone of the report. In this phase, we integrated the different codes and memos and merged the themes and notes that have been repeated in different interviews and focus groups and tried to focus them into key themes. Fourthly, the team worked to analyse the quantitative and qualitative data by putting the similar themes and memos in the main sections of the report. In this phase, we also worked to harmonize the text with the existing literature on social and political trust, by including quotations from participants, making sure of the quality of analysis by triangulating the quantitative and qualitative data, and the existing literature. Finally, we worked on generating a coherent interpretation of social and political trust in the Moroccan context.

Generally speaking, the authors followed a thorough approach and methodology in order to ensure the highest standards of impartiality and balance in their analyses. In this regard, we have taken several steps. First, the quantitative data was collected by a professional company specialized in public opinion research. Their expertise ensured the collection of data from a representative sample representing Moroccan society. Secondly, the collection of the qualitative data has been done with respect for the ethics of research, by explicitly explaining to the interviewees the purpose of the research and getting their approval to record the interviews. Participants in the qualitative research were selected from different backgrounds to ensure a diversity of opinion. Then all interviews have been transcribed, coded and then compiled according to the different themes. Researchers of this report worked as a team to ensure the impartiality of the analysis proposed.

Yet, as in any scientific inquiry, this project has its own limitations. Despite all the efforts aimed at impartiality, the authors are citizens who have their own opinions, passion, and biases. Moreover, academic scholarship has thoroughly scrutinized the claims (as well as the very idea) of absolute neutrality in research, often concluding that complete non-interference does not exist.[7] Furthermore, the project has faced some challenges related to the human and financial resources. For instance, we were unable to conduct interviews in the rural areas and different regions or categories, because we did not have enough researchers to help in this project due to the lack of sufficient financial resources. So far, the authors believe that the quality of the data collected and the steps followed in the analysis render those challenges minimal and make this report of high quality.

Footnotes

[1]Eri Bertsou, ‘Rethinking Political Distrust’, European Political Science Review, 11.2 (2019), 213–30 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000080>.

[2]Hana Brixi, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock, Trust, Voice, and Incentives : Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa (Washington, DC, 2015) <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21607>.

[3]Ibid.

[4]This model has been inspired by the World Bank report cited above.

[5] For more information about the questionnaire, please refer to the appendix of the report.

[6]Barney G Glaser and Anselm L Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Routledge, 1967).

[7]Linda Alcoff, ‘The Problem of Speaking for Others’, Cultural Critique, 1991, 5–32, <https://doi.org/10.2307/1354221>.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

MIPA Institute

MIPA is a non-profit independent research institution based in Rabat, Morocco. Founded by a group of transdisciplinary researchers, MIPA’s mission is to produce systematic and in-depth analysis of relevant policy issues that lead to new and innovative ideas for solving some of the most pressing issues relating to democracy.